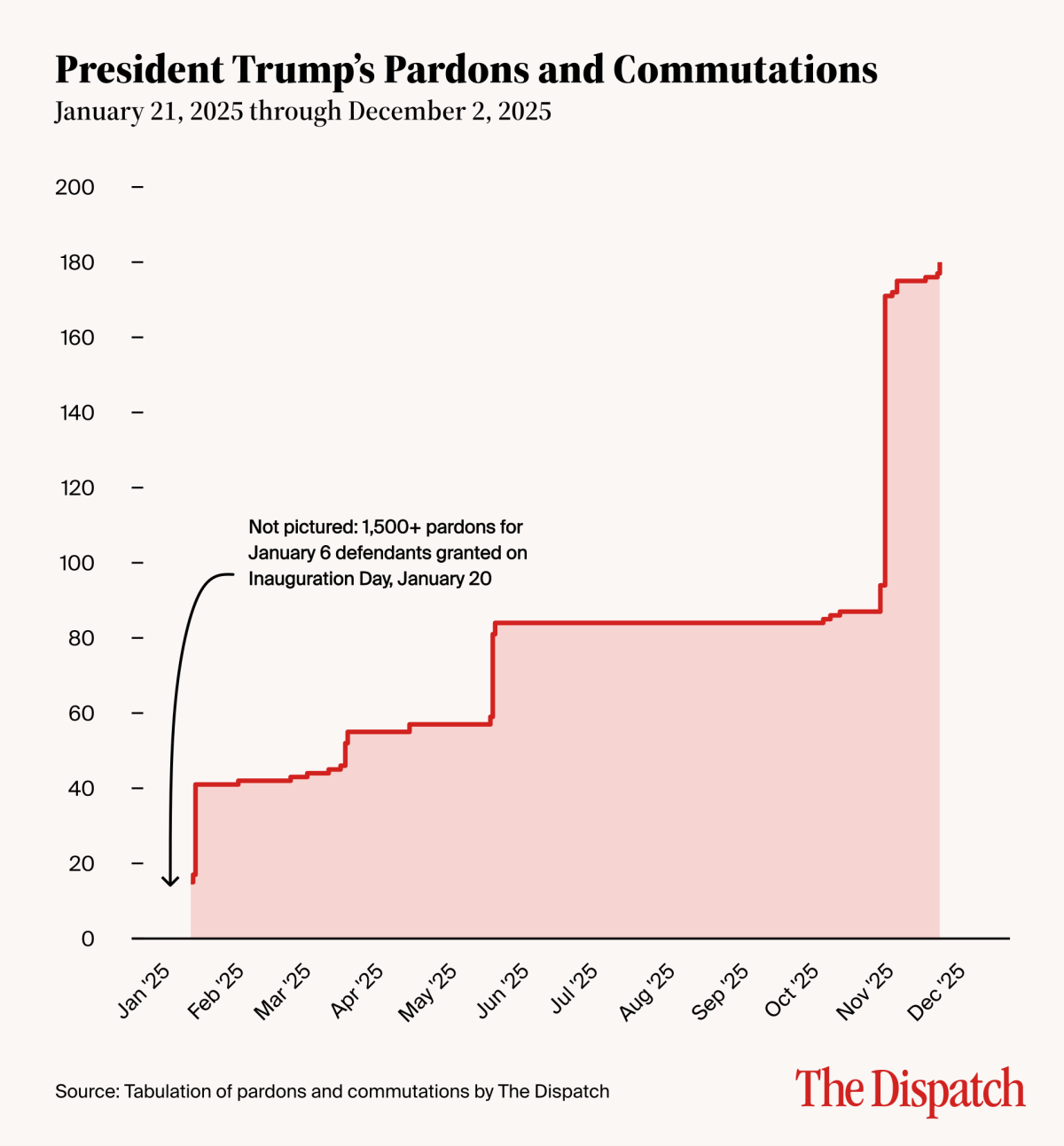

Since his second day in office, Trump has issued pardons or commutations to more than 170 individuals—and on his first day, he signed the largest group pardon since President Jimmy Carter’s 1977 amnesty for Vietnam War draft evaders, pardoning more than 1,500 individuals convicted of or awaiting trial for offenses related to the January 6 Capitol riot, and commuted the sentences of 14 others to time served. Those included people convicted of violent acts, and Oath Keepers militia leader Stewart Rhodes, who—according to the federal district judge who sentenced him to 18 years in jail—“was the one giving the orders” in the Capitol attack.

To make some clear distinctions: A presidential pardon forgives the offense and restores civil rights, while a commutation reduces or eliminates a prison sentence but does not erase the conviction. You can read TMD’s continually updating pardon database here. The White House has been willing to intervene before the pardon stage, with DOJ dropping or settling cases they likely would have won. Crypto investor Roger Ver made a deferred prosecution agreement with the DOJ to settle federal tax charges, paying a $50 million fine, and avoiding trial. It’s also worth noting that a presidential pardon only applies to federal law, and offers no protection from state or foreign prosecution. On Monday, Honduran Attorney General Johel Antonio Zelaya Alvarez announced he had issued an international arrest warrant for Hernández on charges of money laundering and fraud.

Trump had campaigned on pardoning January 6 defendants, which, according to University of Virginia law professor Saikrishna Prakash—author of the upcoming book, The Presidential Pardon: The Short Clause with a Long, Troubled History—is “not exactly novel, because [former President Joe] Biden ran on a promise of pardons for marijuana users, and he fulfilled that.” Similarly, Carter had pledged to pardon the draft dodgers while campaigning. But “I think we might be entering into an era where presidents run on a platform of issuing pardons to certain groups,” Prakash told TMD.

It’s easy to see Trump’s use of the pardon power to help his political allies and base. On at least two occasions during the 2024 campaign, Trump highlighted one of the “peaceful pro-lifers who Joe Biden has rounded up,” Paulette Harlow, whom he described as “a 75-year-old woman in poor health sentenced to two years in prison for singing outside … an [abortion] clinic.” According to federal prosecutors, Harlow and other pro-life activists “forcefully entered” the facility in Washington, D.C., and “set about blockading two clinic doors using their bodies, furniture, chains, and ropes.” On January 23, Trump pardoned 23 pro-life activists charged or convicted with civil rights violations for blocking access to abortion facilities, including Harlow.

Even more strikingly, on November 10, Trump issued a sweeping pardon, naming 77 of his allies—including former New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani, former White House chief of staff Mark Meadows, lawyer and legal adviser John Eastman, and those who served as or supported “alternative electors” in the 2020 election—for their actions taken “to expose voting fraud and vulnerabilities in the 2020 election.” The proclamation explicitly states that the pardon does not apply to Trump himself—but Attorney General Pam Bondi and Pardon Attorney Ed Martin contend they have the authority to determine whether additional individuals and prospective alleged crimes have been granted legal cover.

But Trump’s use of the pardon is broader and less easily explained than just being support for allies. So far, he has pardoned or commuted the sentences of more than 30 people charged with or convicted of financial felonies, including money laundering, tax evasion, and fraud. Eight of those individuals are former public officeholders, three of whom are Democrats: Cuellar, former Detroit Mayor Kwame Kilpatrick (convicted of racketeering and bribery), and former Illinois Gov. Rod Blagojevich.

In December 2011, Blagojevich was sentenced to 14 years imprisonment for a scheme to sell a U.S. Senate appointment for the seat vacated by Barack Obama following the 2008 presidential election for $1.5 million in campaign contributions and other benefits. He was also convicted of “shaking down the chief executive of a children’s hospital for $25,000 in campaign contributions,” according to a Justice Department press release at the time.

Trump granted him a “full and unconditional pardon” on February 10. Last month, Martin posted a photo of himself and Blagojevich on X, writing, “Good morning, America. How are ya’?”

Polling suggests there’s no nationwide silent majority supporting Trump’s pardon usage. An Economist/YouGov poll released earlier this week showed that 58 percent of Americans surveyed said Trump is handing out too many pardons. Two-thirds of respondents disapproved of the pardons issued to both Cuellar and Hernandez. “The larger problem is that it sends a message to the country at large that the rule of law is not the rule of law, that at the highest levels, there can be these arbitrary decisions about people being let off from having committed crimes that they should be in jail for,” Gary Schmitt—a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and former executive director of the President’s Intelligence Advisory Board during the Reagan administration—told TMD. “So it’s not good either for the public spirit or good government.”

Beyond the sheer volume, the pardon process has also changed. “There’s a long-standing process in the Department of Justice for considering pardon applications, and I think that’s all being bypassed,” Prakash said. The standard process requires two initial reviews: first by the pardon attorney’s office, then by a senior Justice Department official. “So, you had a two-stage process right before it got to the White House, and then it would go to the White House, and then the president would decide what to do, with no guarantee that the president would decide to do anything,” Prakash said.

But an increasing number of pardon-seekers have determined it’s easier to contact Trump directly rather than navigate the formal bureaucratic process. And if they don’t have a personal tie to the president, they can hire a lobbyist who does. “A lobbyist can get an official’s attention in a way that a letter might not,” Prakash said.

This isn’t particularly unusual. The lobbying industry for pardons can be traced back to early use of pardon authority in English common law, and other presidents have circumvented the DOJ vetting system. Prakash noted that Biden “obviously” didn’t use the process in pre-emptively pardoning five of his family members on his last full day in the White House. But Trump has expanded on such norm-breaking. “Basically, if someone gets his ear and convinces them that it would be a good idea to pardon a particular person, he does it,” Brian Kalt, a law professor at Michigan State University, told TMD.

Prakash offered two reasons to explain Trump’s pardon-issuing enthusiasm this year. “I think the pardon power is extremely attractive to President Trump, because he doesn’t need to go to Congress, and the courts won’t second-guess the pardon,” he said. And Trump may simply relate to the people he pardons, as people who have also claimed to be victims of politically motivated trials or an unfair justice system. “Now, do they all think that? I don’t think so,” he said. “They know that he thinks he was a victim of that, and they understand human nature, that if they say this, he will feel sympathy for them … because he feels like he was prosecuted for political reasons.”