An Iron Law of Public Policy is that a wonk’s vacation will inevitably coincide with BREAKING NEWS that demands his attention, and my respite last week was no exception. Indeed, mere hours after Capitolism checked out to spend a few delightful days at a Texas dude ranch(!) with limited cell service, President Donald Trump lashed out at a journalist’s question about the “TACO trade” on Wall Street—the view that Trump Always Chickens Out on his tariff threats. Mere minutes after that, the U.S. Court of International Trade (CIT) released one of the biggest court decisions in trade policy history when it invalidated and enjoined Trump’s biggest and broadest tariffs under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA). The next morning, a D.C. district court released another, narrower ruling against those same tariffs—but this time involving a small business owner I interviewed in late April. And, just hours after that, Trump announced he was doubling steel and aluminum tariffs—an order that took effect yesterday.

The court decisions were immediately cheered by fans of freer trade and the rule of law, and they set off a flurry of analyses (and stock market rejoicing) about the future of U.S. trade policy now that both Trump’s fentanyl tariffs and “Liberation Day” (reciprocal) tariffs were canceled. The cheers died down a bit after both rulings were temporarily paused until at least mid-June pending further deliberations by U.S. appellate courts.

For reasons we’ll discuss today, the decisions are still very important for both U.S. trade policy and the rule of law. But as Trump’s latest steel and aluminum moves show, the U.S. tariff fight is just getting started.

A Big Freaking Deal

Although the courts’ rulings have been temporarily stayed, they remain very significant. As we discussed last year, legal and trade policy experts were divided on the questions of whether IEEPA allowed the president to impose tariffs (especially broad ones like those Trump imposed earlier this year); whether, if the law did allow for such measures, it was a proper (i.e., not overbroad) delegation of Congress’ constitutional tariff power; and—perhaps most importantly—whether U.S. courts, particularly deferential to presidential powers where foreign policy and national security are ostensibly involved, would rule against the president, even when the first and second questions warranted it.

There were also important practical questions about how quickly any rulings against the tariffs would come and whether a court would let them remain in place while deliberating: A lower court ruling that the tariffs are illegal or unconstitutional is worth much less to a financially strapped plaintiff if he’s paying those taxes for months or even years while the lawyers are doing their thing, and it was unclear whether a company could meet the legal requirements for getting the tariffs stopped (enjoined) in the meantime.

Of course, scholars like the Cato Institute’s Ilya Somin—one of the lawyers/heroes in the CIT case—had good legal arguments against these tariffs, particularly the administration’s contradictory claims that IEEPA gives the president effectively unlimited tariff powers yet remains a proper delegation of those same powers, which the Constitution expressly gives to Congress. (Indeed, prominent constitutional scholars on the right and left intervened in the case to challenge this very thing.) Nevertheless, not everyone agrees with Somin, and it was simply remarkable that two different U.S. courts—and four different judges with widely varying backgrounds (including one Trump appointee)—would quickly and unanimously rule in plaintiffs’ favor on basically all the above questions, on all IEEPA tariffs, and—in the CIT case—for all U.S. importers. It’s even more remarkable given that the Trump administration worked hard to move all litigation to the CIT, which was considered more deferential to presidential trade powers than other venues. And those judges—again, unanimously—even questioned the president’s determination that fentanyl trafficking constituted an “unusual and extraordinary threat” that can be dealt with by IEEPA.

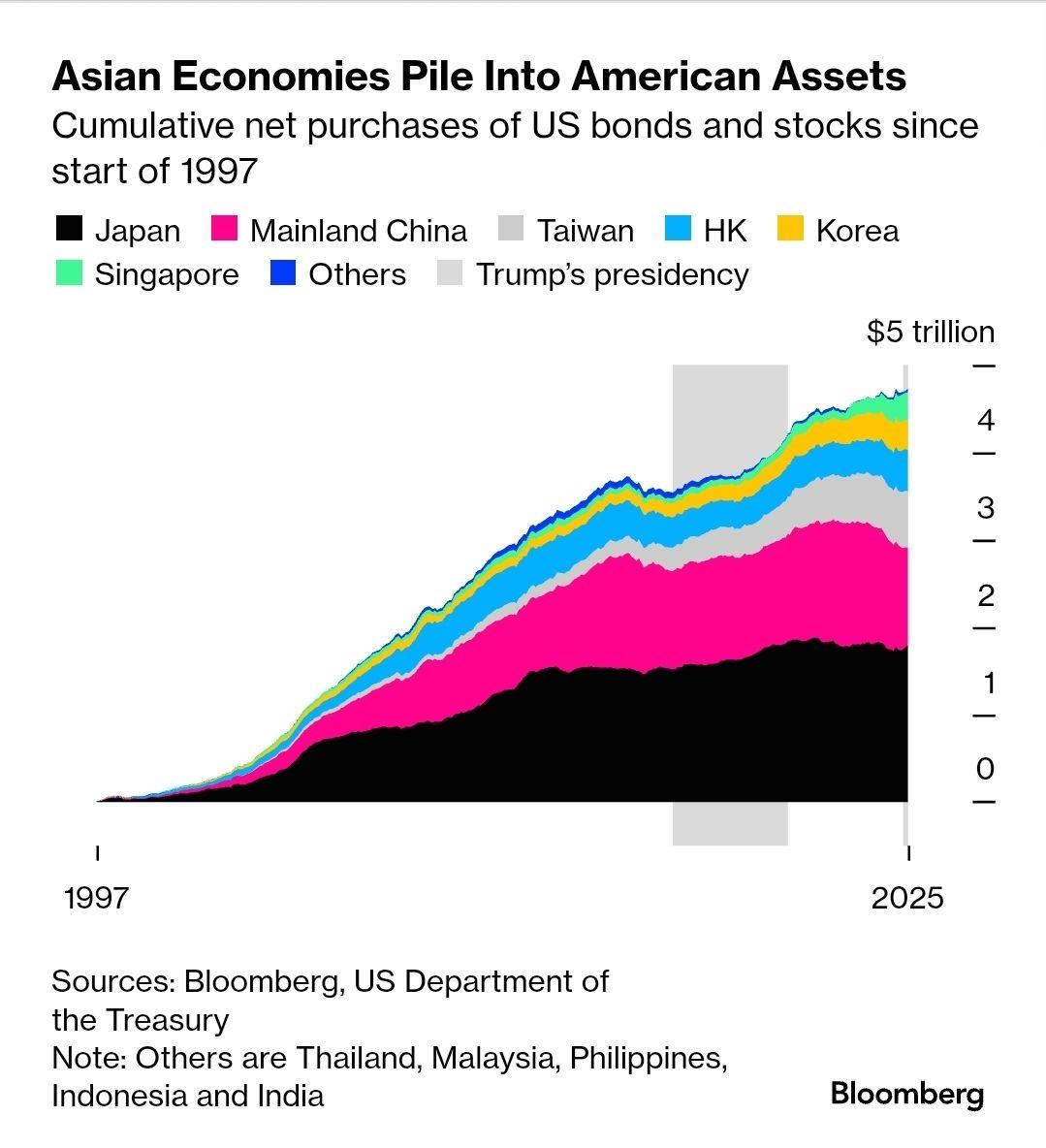

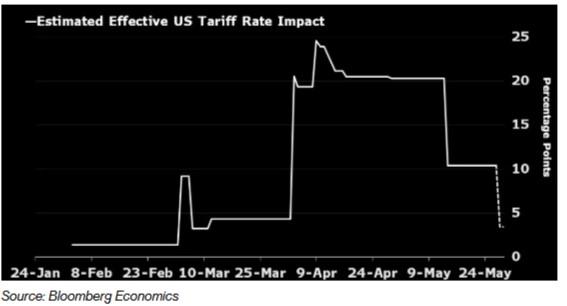

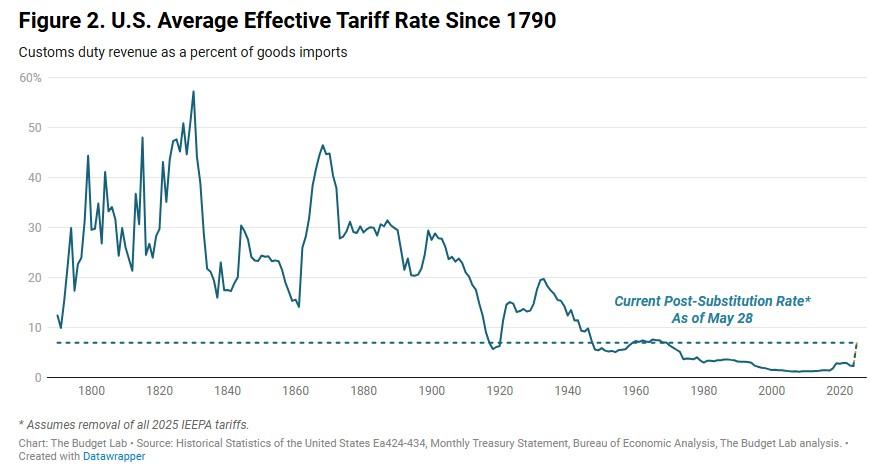

The rulings’ potential economic effects are also substantial because the IEEPA tariffs were by far the biggest and broadest of Trump’s new import taxes. According to the Yale Budget Lab, in fact, invalidating all the IEEPA tariffs would cause the average effective U.S. tariff rate to drop approximately 10 percentage points from around 17 percent to 7 percent, thus nixing about $2 trillion in future revenue over the standard 10-year budget window while also significantly dampening the tariffs’ price increases and GDP reductions. The static reduction in U.S. tariffs (meaning no shifting of trade flows) would be even more dramatic:

Companies caught in the crosshairs of these tariffs would be similarly affected, especially smaller importers who couldn’t easily shift suppliers or hoard inventories and were thus faced with choosing between paying huge new tax bills or simply shutting down. Now, all those companies will—if the rulings are upheld—enjoy not only prospective tariff relief but also refunds for any duties paid. Protected companies, of course, would see the opposite effects.

Overall, it’s undeniably “one of the biggest setbacks of the president’s second term.” (Oh well!)

Not Out of the Woods Yet

Unfortunately, that “if” above gets to one of the many reasons to hold off celebrating these victories too much. Most obviously, the rulings have been stayed pending further review by appellate courts, and tariffs will thus remain in force until at least June 9 when the U.S. government’s brief is due to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC), which oversees the CIT. At that time or shortly thereafter, the CAFC will decide whether to extend the stay during the appellate proceedings, meaning the tariffs could, if the stay is extended, be in force for several more months while the court (and/or the U.S. Supreme Court) deliberates. It could therefore be a long while before these cases are fully resolved, and U.S. importers could be paying literally billions of dollars in the meantime. We’ll know more in a couple of weeks.

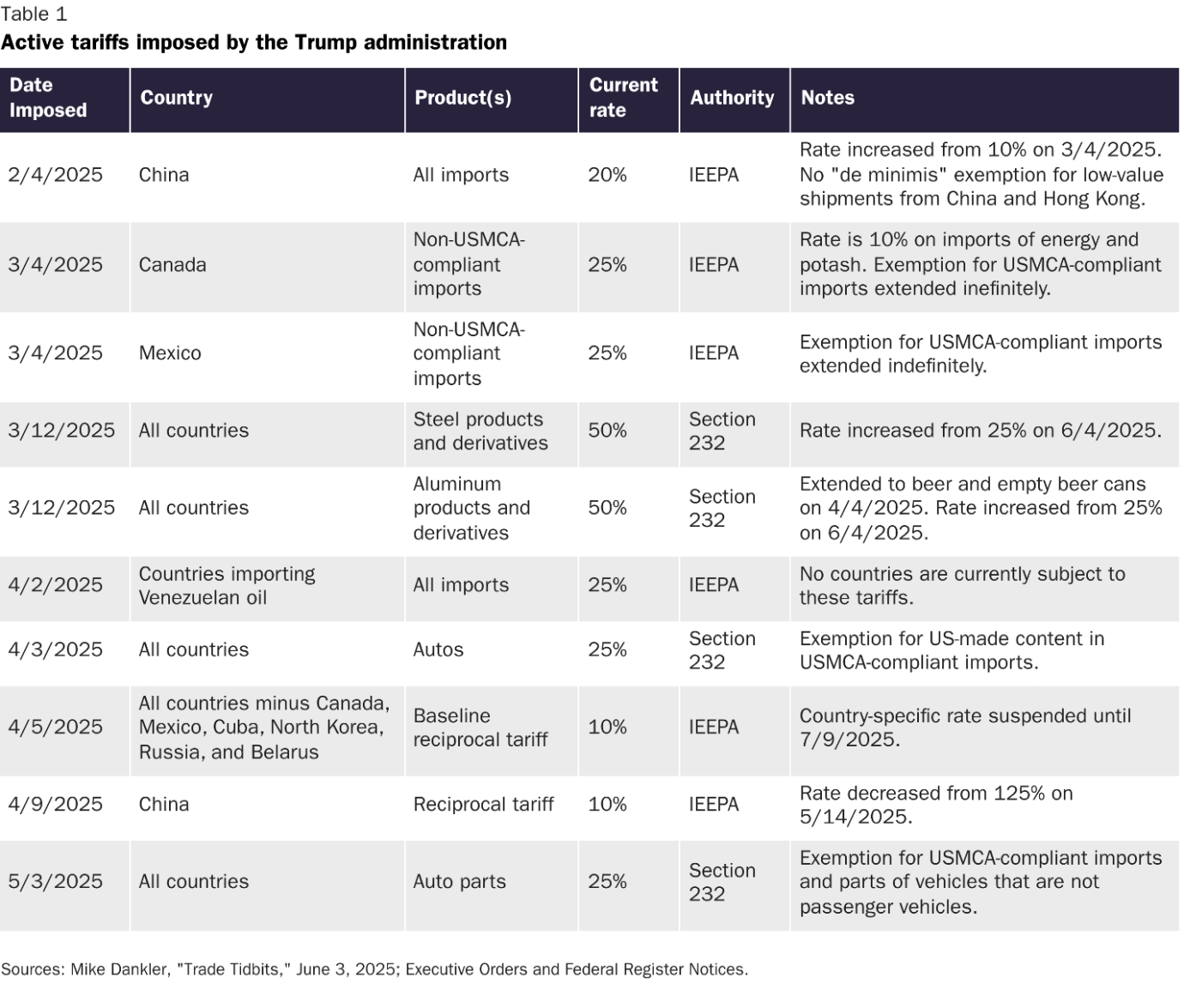

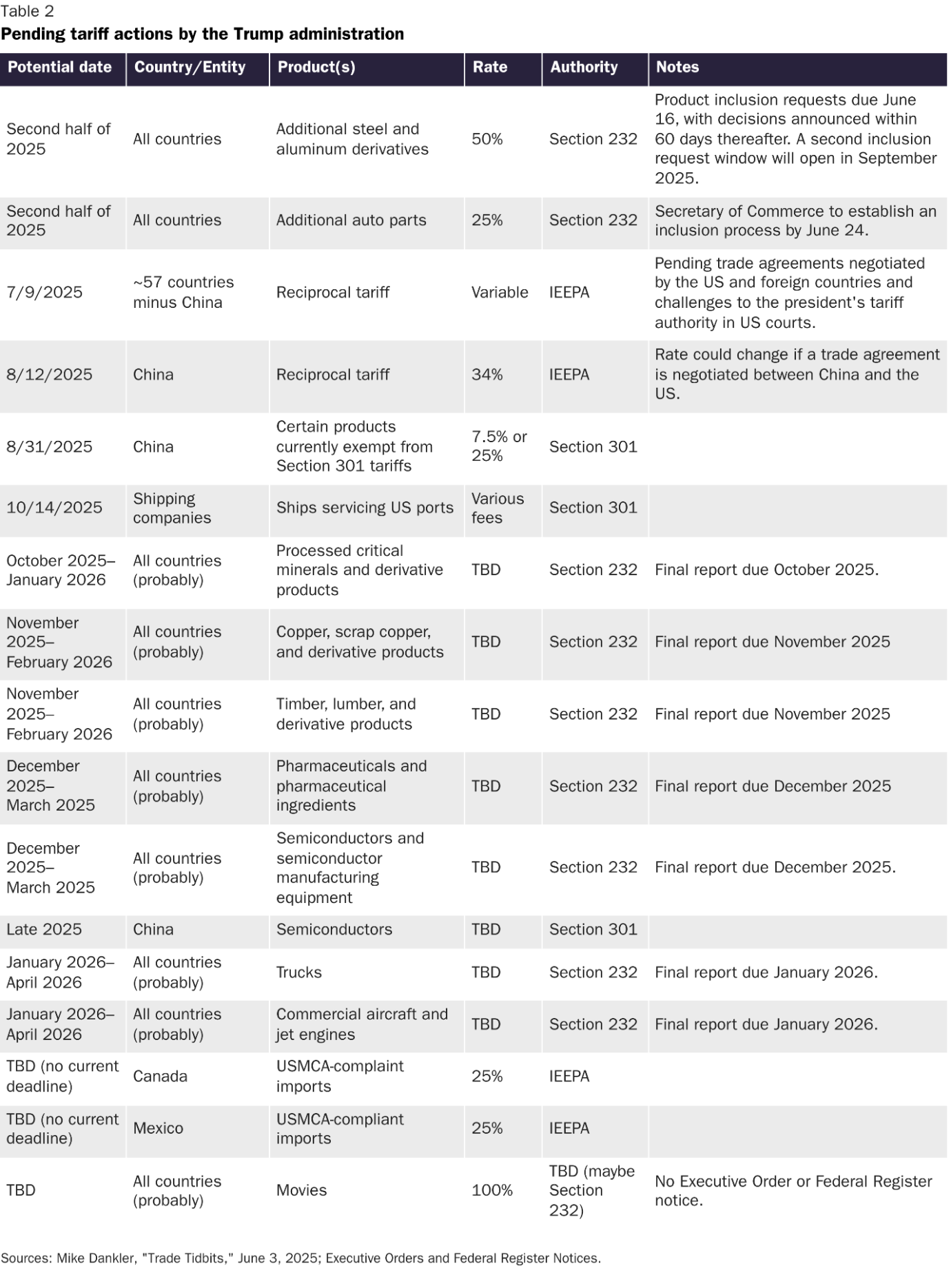

Just as important, all the other Trump tariffs remain in effect, including 1) the “Section 301” tariffs of up to 25 percent on around half of all Chinese imports; 2) the global “Section 232” tariffs on steel and aluminum, which Trump earlier this year expanded to cover more countries and products and just yesterday increased to 50 percent (yikes); and (3) the 25 percent “Section 232” tariffs on automotive goods (cars and parts) from all countries except—in some cases—Canada and Mexico. Here’s a handy summary of where things stand:

Though not as big or broad as IEEPA, these tariffs remain economically significant. As the Yale Budget Lab’s analysis shows, even assuming all the IEEPA tariffs disappeared and no others appeared (more on that in a second), the average U.S. tariff rate would still be the highest since 1969, equating to a new $950 tax on every American household and reducing U.S. GDP by tens of billions of dollars each year. Other analyses of the non-IEEPA tariffs, such as the one from the Tax Foundation, show similar harms.

Chief among these remaining taxes are the ones on imported automotive goods. As economist Joseph Politano rightly noted, if it weren’t for the IEEPA stuff, the auto tariffs—imposed this year based on an investigation undertaken in 2018!—“would be the single-largest economic story of the year,” alone hitting “more than $353B in US imports” and “having a larger economic effect than all of the tariffs implemented during Trump’s first term combined.” Most people ignore this because the IEEPA tariffs—and the global market meltdown that followed them—moved the Overton window so far into Tariff Crazytown that these and other tariffs seem sane by comparison.

Furthermore, Trump has no intention of pulling back on tariffs just because some pesky judges might eventually curtail one particularly aggressive method of applying them, and there remain several other laws for Trump to utilize. As the recent steel and aluminum moves demonstrate, for example, administration officials can increase existing tariffs’ magnitude and scope under either Section 232 or Section 301. They also have initiated several other investigations under these laws and have threatened even more in the future:

The Wall Street Journal adds that, if the courts do ultimately strike down the IEEPA tariffs or the law itself, the administration is ready to use 232, 301, or other U.S. trade laws to effectively re-create the global baseline tariff by other means. Most notable in this regard are, as I previewed last year, two old statutes that confer broad tariff powers but have never been used:

- Section 338 of the Tariff Act of 1930 is a short and ambiguous law that authorizes the president to impose tariffs of up to 50 percent on imports from countries that have “discriminated” against U.S. commerce as compared to what another foreign nation does.

- Section 122 of the Trade Act of 1974 empowers the president to unilaterally address “large and serious” balance-of-payments deficits via global tariffs of up to 15 percent for no more than 150 days (after which Congress must act to continue the tariffs). The CIT mentioned this law as the more appropriate way to address the trade deficit “emergency” that supposedly justified the Liberation Day tariffs imposed under IEEPA.

Finally, there’s the perilous question of what foreign governments will do as we approach the July 9 deadline for the (now maybe illegal?) “Liberation Day” tariffs that Trump suspended in April. So far, the administration has still only completed two deals—with the U.K. and China—to avoid higher duties after the deadline, but both are vague and incomplete. The China truce is also just temporary, and both sides are already angry over the other’s supposed noncompliance. What happens next is anyone’s guess, but more and higher tariffs are certainly a possibility—from both sides.

For all other countries, meanwhile, there’s little indication of the number or content of deals that might get inked in the next month, and the court rulings—along with China’s open defiance and the administration’s blatant protectionism—give U.S. trading partners both an incentive to wait at least a few weeks for more clarity from the CAFC and much more leverage in any ongoing discussions (as the administration itself admits). As a result, governments could slow-walk the talks, demand bigger U.S. tariff cuts (and offer less in return), or become more forceful about possibly retaliating if “reciprocal” and other U.S. tariffs take effect. As Bloomberg reported yesterday, in fact, India is doing these very things. How Trump responds, especially after the TACO callout, is anyone’s guess.

In short, given the president’s TACO-bruised ego and proclivity for tariffs, we should expect more of them in the months ahead—and more costs and uncertainty along the way—regardless of what the courts do later this year on IEEPA. And, as the Financial Times’ Alan Beattie reminds us, we should expect other, non-tariff restrictions on trade and investment, too.

But Still …

None of this means, however, that last week’s court rulings aren’t important. First and most obviously, the rulings cast new and surprising doubt on inarguably the most dangerous and powerful law under which a president might try to impose tariffs or other trade restrictions. As Trump has repeatedly demonstrated this year, IEEPA ostensibly lets a president instantly impose trillions of dollars in new and permanent U.S. taxes on imports from friends and foes alike—taxes paid mainly by Americans and deployed for the thinnest of reasons with absolutely zero input from Congress or the public.

As I wrote last year, by contrast, all the other laws Trump might use have procedural checks and/or substantive weaknesses that make the rapid imposition of global tariffs more difficult, time-consuming, and/or temporary. As Bloomberg detailed last week, for example, Section 122 has its own limitations—beyond the 15 percent cap and 150-day limit. Even Section 338, which is just a few sentences long, has more limits on the size and scope of potential unilateral tariffs than does IEEPA. Tariffs can’t exceed 50 percent, for example, and can’t apply globally.

Furthermore, the CIT unanimously enjoining the IEEPA tariffs is a clear sign that, as Somin just noted, mainstream judges from across the political spectrum both understand the serious economic harm caused by continuing the tariffs (even if they’re eventually refunded) and harbor serious skepticism that a president can unilaterally impose trillions of dollars in new federal taxes simply by declaring a (bogus) national emergency. As one law firm aptly put it:

The CIT’s decision represents a significant limitation on the president’s ability to unilaterally impose tariffs under IEEPA, reaffirming the constitutional role of Congress in regulating international trade and imposing duties. The court’s reasoning underscores the importance of statutory limits and legislative intent in delegating emergency powers to the executive branch. The CAFC’s temporary stay leaves the ultimate resolution pending, but the CIT’s analysis provides a clear framework for evaluating future exercises of emergency economic powers. Legal professionals and importers should closely monitor further developments in these consolidated appeals, as the outcome will shape the contours of executive authority in trade and emergency contexts for years to come.

The decision must therefore give administration officials pause about continuing to rely on IEEPA in the months ahead as litigation remains pending, despite what they might be saying publicly. And it indicates that U.S. courts might be similarly skeptical of broad invocations of Sections 338 and 122, even in a more limited form.

Finally, the court rulings show, as I presciently explained in the Washington Post recently, one reason why Congress cannot and should not rely on Trump’s unilateral tariffs to offset the revenue losses generated by the Republican One Big Beautiful Bill Act that just passed the House:

As of today, there are seven legal challenges to tariffs that Trump imposed this year under IEEPA, which many legal scholars believe was either not intended for blanket tariffs or is an impermissible delegation of Congress’s constitutional authority to regulate trade. Because IEEPA underlies Trump’s biggest, broadest tariffs (including his blanket “Liberation Day” taxes), a single court ruling against them or the law would mean trillions less in revenue. And even if a court refused to enjoin the tariffs while judicial proceedings are ongoing, recent precedent — a 2019 challenge to Trump’s Section 232 tariffs on Turkish steel — indicates that a final ruling could come in as little as 18 months.

(As you can see, even I wasn’t expecting a quick injunction.)

As I go on to explain in the Post, there are other reasons beyond the litigation to avoid relying on tariff revenue, but last week’s rulings hammer home the risks of doing so. Hopefully Congress listens.

Summing It All Up

The rulings against Trump’s IEEPA tariffs are a landmark victory for the plaintiffs and their lawyers, the U.S. economy, the Constitution and rule of law, and an American legal system in which a few Davids can still beat the Beltway Goliath. Even many who question the courts’ reasoning see other judicial threats to the tariffs on the horizon—especially at a “conservative” Supreme Court that’s increasingly skeptical of unchecked executive power.

This doesn’t mean, however, that the fight over U.S. tariff policy is over: Even if the rulings are upheld on appeal, there are several other laws that grant the president almost as much power to disrupt global trade, and his administration has every intention of testing its limits. TACO bets against big tariffs might work for day-traders, but they’re not a sound strategy for achieving better U.S. trade policy over the longer term. That still requires Congress—in particular, passage of legislation limiting and defining all unilateral trade powers, not just those under IEEPA. GOP lawmakers might be quietly cheering the courts’ decisions last week, but there’s still more work to do.

Chart(s) of the Week