Authored by Lars Møller via American Thinker,

History is replete with revolutionary figures who transformed society through “vision”, “vanity”, and “violence” – a vicious triad covering the strategy of being ideologically uncompromising, outmaneuvering rivals, and eliminating political opposition, respectively.

Maximilien Robespierre and Vladimir Lenin stand out as architects of radical political transformation. Bridging the cultural divide, their leadership styles and psychological profiles show striking similarities. Both men were pedantic ideologues driven by an unshakable belief in their own moral and intellectual superiority.

A comprehensive personality profiling of Robespierre and Lenin requires an analytical framework that transcends ideological taxonomy and historical contingency. While both men operated under conditions of revolutionary crisis, their responses to this strain were neither inevitable nor merely situational. Rather, the extremes of savagery that they authorized, rationalized, and sustained reflect enduring psychological structures that shaped their political conduct. Revolutionary atrocity, in this sense, is best understood, not as an accidental excess of upheaval but as an expressive manifestation of personality under pressure.

At the center of both profiles lies a distinctive form of narcissism, albeit one that diverges from popular caricature. Neither Robespierre nor Lenin cultivated flamboyance or sensual excess. Instead, they embodied a restrained and severe narcissism, grounded in ascetic discipline and intellectual or moral exclusivity. This “austere narcissism” is particularly insidious, as it disguises grandiosity beneath the rhetoric of sacrifice and historical necessity. Both men perceived themselves as uniquely attuned to the demands of history, endowed with a clarity unavailable to others. This conviction constituted the psychological foundation of their authority and simultaneously foreclosed the possibility of self-doubt.

Robespierre’s personality was organized primarily around moral absolutism. His self-conception as l’Incorruptible was not a mere political posture but a deeply internalized identity. Personal frugality, emotional restraint, and rhetorical solemnity served as symbolic reinforcements of moral superiority. From a psychological standpoint, this configuration suggests a rigid superego structure in which ethical norms were internalized as categorical imperatives rather than negotiable principles. Moral conflict could not be accommodated; it had to be eradicated.

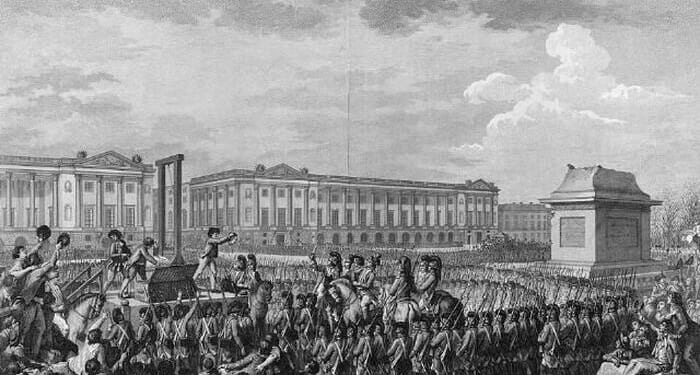

This psychic architecture is indispensable for understanding Robespierre’s embrace of terror during 1793–94. The Law of Suspects, enacted on September 17, 1793, dramatically expanded the definition of counter-revolutionary guilt to include vague categories such as “enemies of liberty” and those lacking “civic virtue”. In practice, this legislation enabled the arrest of tens of thousands on the basis of suspicion alone. The resulting mass incarcerations and executions were not only tactical responses to military threats but also expressions of Robespierre’s moralized worldview. Political ambiguity itself became criminal.

The Revolutionary Tribunal exemplified this moral reductionism. Legal safeguards were progressively dismantled, culminating in the Law of the Great Terror, enacted on June 10, 1794, which eliminated defense counsel and limited verdicts to acquittal or death. The acceleration of executions—over 1,300 in Paris alone within six weeks—reflected not panic but moral certainty. Violence functioned as ethical enforcement. The guillotine, with its mechanical regularity, transformed killing into procedure, allowing Robespierre to experience mass death as impersonal justice rather than cruelty. Psychologically, such depersonalization constitutes a dissociative defense: suffering is abstracted, responsibility displaced, and violence reclassified as virtue.

Robespierre’s increasing hostility towards former allies further reveals the fragility underlying his moral absolutism. The executions of Georges Danton and Camille Desmoulins—longstanding revolutionaries accused of “indulgence”—illustrate how moral rigidity devolved into paranoid purification. Dissent was no longer external but internal. The purges thus served not only political consolidation but also psychic stabilization. Each execution reaffirmed Robespierre’s self-image as guardian of revolutionary purity against an ever-expanding field of corruption.

Lenin’s psychological profile, though equally absolutist, was structured along a different axis. His narcissism was intellectual rather than moral. Lenin did not portray himself as virtuous but as scientifically correct. Authority derived from his conviction that he alone grasped the objective laws of historical development. This intellectual narcissism produced profound disdain for spontaneity, pluralism, and moral hesitation.

Lenin’s approach to violence during and after the October Revolution exemplifies this orientation. The establishment of the Cheka in December 1917 marked the institutionalization of terror as a permanent instrument of governance. Unlike the revolutionary tribunals of 1793, the Cheka operated extrajudicially from the outset. Its remit included summary execution, hostage-taking, and mass repression. Lenin explicitly endorsed these measures. In correspondence from 1918, he called for “merciless mass terror” against class enemies, insisting that hesitation would doom the revolution.

The Red Terror of 1918–22 provides stark illustration. Following the attempted assassination of Lenin in August 1918, the regime launched widespread reprisals. Thousands were executed without trial, often selected, not for actions but for social origin. Former nobles, priests, merchants, and officers were targeted as categories rather than individuals. The mass shootings at Petrograd and Moscow, as well as the use of concentration camps—precursors to the Gulag system—demonstrate how violence was bureaucratized and de-personalized. Psychologically, this categorical annihilation reflects cognitive reductionism: human beings were reduced to structural obstacles to be removed.

The suppression of the Tambov peasant uprising (1920–22) further illustrates Lenin’s instrumental rationality. When peasants resisted grain requisitioning, the Red Army deployed poison gas, mass deportations, and hostage executions. Lenin personally authorized these measures, framing them as necessary to break “kulak resistance”. The scale and severity of the repression—tens of thousands killed or interned—underscore his willingness to annihilate entire populations in pursuit of economic and ideological objectives. Emotional detachment was not incidental but functional: empathy would have impeded efficiency.

Similarly revealing was the crushing of the Kronstadt rebellion in 1921. The sailors, once celebrated as heroes of the revolution, demanded free elections and an end to Bolshevik repression. Lenin and Trotsky responded with overwhelming force. Thousands were executed or sent to labor camps. The psychological significance lies in the readiness to destroy former allies once they ceased to serve the ideological script. Dissent, regardless of origin, was pathologized as counter-revolution.

Despite stylistic differences, Robespierre and Lenin shared a fundamental incapacity to recognize others as autonomous moral agents. From a developmental psychology perspective, this suggests impaired “mentalization”. Opposition was interpreted, not as disagreement but as moral corruption or structural deviance. Consequently, violence acquired an air of inevitability.

Both leaders also exhibited marked emotional austerity and social withdrawal. Their reluctance to engage in ordinary social life reinforced authority but deepened isolation. Isolation intensified suspicion. Deprived of corrective feedback, both increasingly relied on internal narratives of betrayal. Terror became self-reinforcing: fear confirmed paranoia, paranoia justified repression, and repression entrenched power.

This dynamic accords with established models of authoritarian personality, which emphasize the interplay between dominance and insecurity. Such leaders are not psychologically secure. Their need for absolute control compensates for internal fragility. Power functions as an external stabilizer, imposing order upon both society and the self.

The handling of failure further illuminates these personalities. Neither Robespierre nor Lenin demonstrated genuine self-criticism. Military setbacks, economic collapse, or popular resistance were invariably attributed to insufficient repression. Violence thus substituted for reflection. Rather than revising assumptions, both escalated coercion.

The persistence of terror beyond immediate necessity underscores its expressive function. Once institutionalized, violence became ritualized, reaffirming alignment with virtue or history. Each execution symbolized inevitability and correctness. Atrocity communicated omnipotence.

The contrast between Robespierre’s “moralized terror” and Lenin’s “instrumental terror” reflects divergent emotional economies within a shared absolutist framework. Robespierre’s violence was theatrical and ethical; Lenin’s procedural and technical. Yet both converged in their effect: the annihilation of individuality and the normalization of death as a political tool.

Ultimately, the personality profiling of Robespierre and Lenin demonstrates how revolutionary leadership magnifies latent psychological traits. Ideology supplied justification; crisis provided opportunity; personality determined execution. Their atrocities were not historical aberrations but behavioral culminations of rigid cognition, narcissistic self-identification, emotional detachment, and intolerance of uncertainty.

The broader implication is sobering. Extreme political violence need not arise from overt sadism. It often emerges from moral certainty, intellectual arrogance, and the refusal to acknowledge human complexity. Robespierre and Lenin exemplify how revolutionary ideals, when filtered through psychologically brittle leadership, can transmute aspirations of emancipation into systems of terror. Their legacies endure as warnings of what occurs when conviction eclipses conscience and abstraction supplants humanity.

Without any mitigating self-irony, Robespierre and Lenin embodied an unlimited commitment to ideology, indifferent to the concerns of ordinary people, their lives and freedoms.

Loading recommendations…