Dynamic pricing is coming to the 2026 World Cup—and fans are already crying foul. No sooner was the announcement made by FIFA, the international governing body of soccer, than Zohran Mamdani, the leading candidate for mayor of New York City and a democratic socialist, said he had started a petition to press FIFA to drop the pricing plan and “put game over greed.”

By using dynamic pricing—where prices can change based on demand, as with Uber’s surge pricing—FIFA can now “figure out in real time how much they can get away with for charging a ticket,” claimed Mamdani. This is bad news for working-class New Yorkers, he says, leaning into the camera. “… The biggest sporting event in the world is happening in your back yard—and you’ll be priced out of it.”

But is FIFA—and every other practitioner of dynamic pricing from Uber and Amazon to Marriott, Delta, and Target—really playing dirty? Are they price-gouging their customers, as populists like Mamdani insist, or are they improving their bottom line while offering a better overall deal to consumers?

One price for all.

Dynamic pricing is very different from uniform pricing, where a product or service has one price, no matter who’s buying or when (apart from discounts, introductory offers, and other sales campaigns).

As used to it as we are now, uniform pricing was once an economic innovation as radical as dynamic pricing seems today. A single good might have several prices, depending on the quality of the specific item, which before mass production could vary greatly. And under the prevailing practice of haggling, those with less leverage were at a disadvantage.

In the mid-1800s, department store innovator John Wanamaker took the one-price-for-everyone approach credited to the Quakers, who believed haggling over price was unfair. And he became something of an “evangelist for the price tag,” according to the Planet Money podcast. Wanamaker saw both the branding benefit of uniform pricing—it appeared equitable to customers—and its practical benefit in speeding up transactions.

The adoption of uniform pricing grew in tandem with the rise of the department store, from its birth in the mid-1800s to its gradual decline starting about 100 years later, when these stores were outcompeted by discounters and other retailers with lower cost structures. Today, consumers consider uniform pricing normal, if not always fair.

And yet, one price for all isn’t necessarily fair, either to businesses or consumers. In fact, there were always good intuitive counterexamples to uniform pricing. To take just one, a room at a resort is worth much more in peak season than in the offseason—and prices reflect this reality.

If, for some reason, that resort can’t adjust its prices, it has a very difficult decision on its hands: charge for the peak times and price itself out of business the rest of the year, or charge at consistent, below-market rates and risk not bringing in enough revenue to meet its costs. Potential guests would suffer, too: Either fewer would be able to afford to stay, or a flood of guests would have an increasingly bad experience, as the resort couldn’t afford to adequately pay its workers and service and maintenance would suffer.

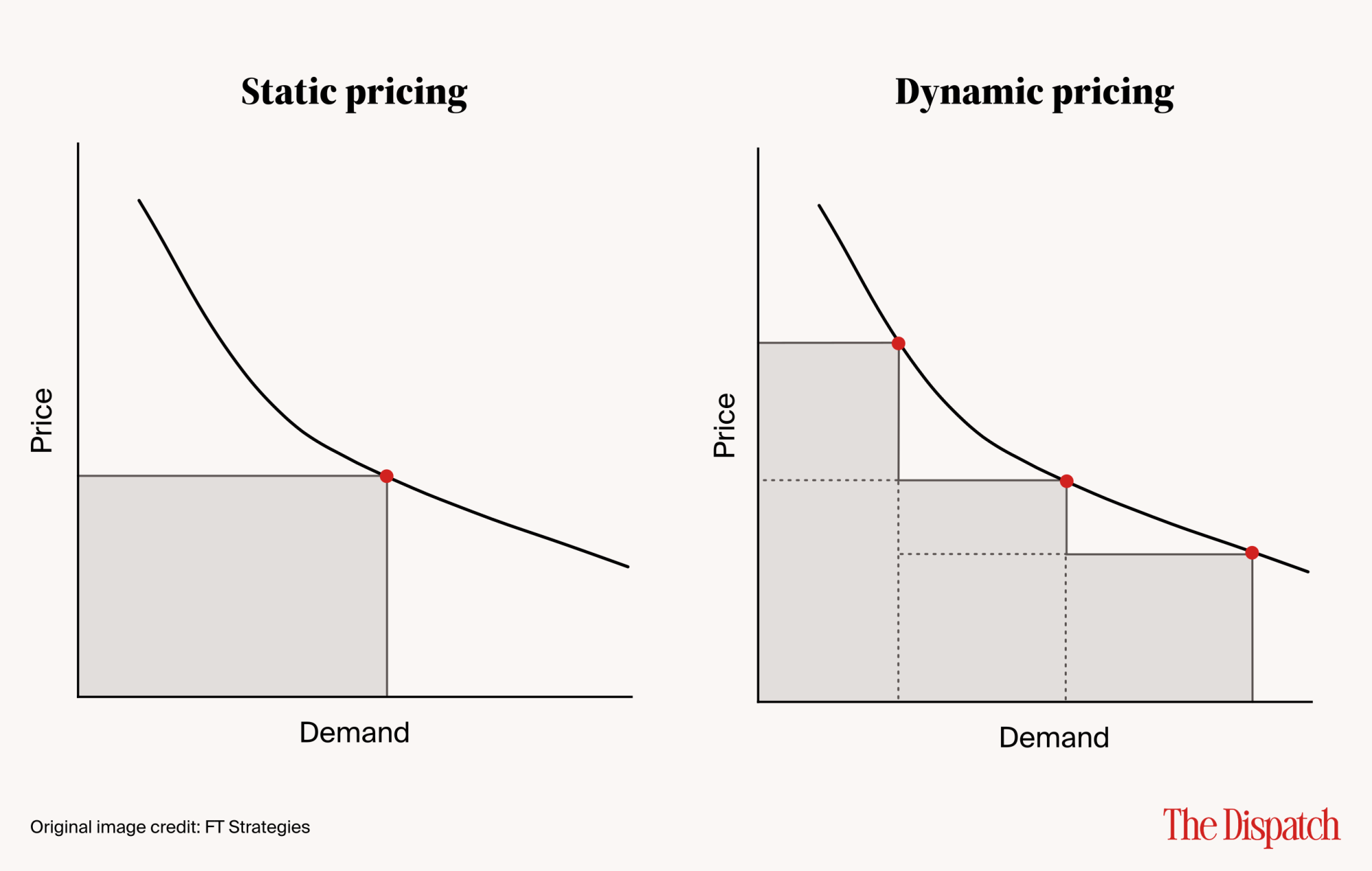

If the price people are willing to pay falls on a curve, as some of us learned in economics class, a uniform price can meet demand at only one point on that curve. Dynamic pricing can theoretically meet at many points along that curve:

“Dynamic pricing helps match supply to demand more efficiently,” as a recent report by the Mercatus Center at George Mason University puts it, “by incentivizing consumption during low-demand periods and disincentivizing it when there is an excess of demand relative to supply.”

The rise of dynamic pricing.

The straitjacket of uniform pricing first began to loosen in the airline industry. After the industry deregulation of the late 1970s, competition began to intensify as discount providers such as People Express entered the space. In response, American Airlines, a pioneer of early dynamic pricing, cut prices on tickets purchased far ahead of time and charged as high a price as demand could support on tickets purchased days before departure.

The adjacent hotel and rental-car industries soon followed. The tool all of these industries utilized to inform their pricing decisions? Data. For airlines, it was centralized reservation systems such as SABRE, Apollo, and others, which also benefited car rental reservations. Hoteliers had built similar systems in-house. All these systems contained real-time data on future demand—crucial for dynamic pricing.

With improvements in technology and computational power, as well as the rise of the internet, this data advantage has exploded. Businesses were gaining more access to more information on buyers, transactions, inventory, and competitor pricing—as well as the interactions of these elements with one another.

In the last decade, artificial intelligence has added predictive power to the mix of tools businesses now can use in adjusting prices to demand. Today, dynamic pricing isn’t just about incorporating past data into prices, but also predictions about future demand. Dynamic pricing is one of the principal ways retailers are using AI, according to the consulting firm Deloitte.

This has helped businesses recapture the value lost in traditional transactions. Amazon taps its own historical price data, drawing inferences from past price changes and sales, predicting future demand—and changing prices on millions of items, several times a day. Dynamic pricing may have increased Amazon’s profits in some years by as much as 25 percent.

But the value-capturing improvements of dynamic pricing don’t come easy. Such pricing calls for data comparisons across many customer and competitor dimensions, the development of algorithms, and testing before the pricing system goes live. It’s also a big investment in people and technology.

Theory meets human.

Dynamic pricing is a true balancing act—because it involves people, with all our biases, notions of fairness, and tendencies toward irrationality. Consumers generally understand they’ll have to pay more for a snow blower in January than in July. But they don’t like unpredictable price changes, as Harvard Business Review points out, or when frequent price fluctuations make life harder. Dynamic pricing is also “a massive communications effort.”

Consumers generally default to skepticism, as Wendy’s, JetBlue, and Legoland found out following announcements about adopting dynamic pricing. They may confuse it with the practice of personalized pricing—using personal information, such as a customer’s home address, to determine what price they’ll be charged. Or they may experience Uber surge pricing during a snowstorm and feel it’s simply price gouging.

It’s an understandable reaction, but also wrong. As economics writer James Surowiecki puts it, Uber’s algorithmic surge pricing “expands the number of people who are actually able to get a ride” by offering a higher price to get more Uber drivers (who are contractors to be persuaded, not employees to be ordered around) out on the road picking up customers.

“Customers pay more, but they also get a ride that they otherwise would not have gotten. This is exactly how a market is supposed to work: higher demand induces more supply.”

Mamdani’s accusation that FIFA is price gouging might appeal to our default assumption that we’re one transaction away from getting ripped off, but dynamic pricing allows prices to fall when demand falters. For example, dynamic pricing was used during the recent FIFA Club World Cup tournament, and ticket prices for a semifinal at New York’s MetLife Stadium between Chelsea and Fluminense fell to less than $15.

A lower, fixed price for World Cup tickets might allow more deserving New Yorkers of modest income to get tickets—if they can get them. Because, as The Athletic observed, lower prices also create an incentive for scalping—a problem FIFA is trying to solve in part with dynamic pricing. A ticket scalped several times over benefits no one but the scalpers, not working-class New Yorkers, much less the average consumer.