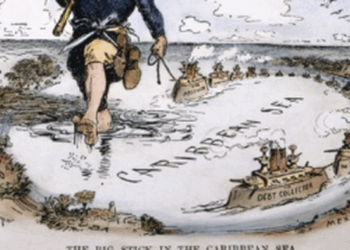

In their timely new book, In Covid’s Wake: How Our Politics Failed Us, Stephen Macedo and Frances Lee provide a searing indictment of public health experts’ and political elites’ response to the COVID pandemic that imposed on the American citizenry restrictions “more sweeping and disruptive than any that had been previously contemplated in Western pandemic plans.” Starting in March 2020, these included stay-at-home orders, mandated mask wearing, and the closure of schools, businesses, and sporting events. The imposition of these non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) raised three serious questions: First, could they prevent, or significantly slow, the spread of a highly contagious respiratory virus (at least until a vaccine became widely available)? Second, what health, economic, and social costs did these interventions themselves impose? And third, did the costs of the policies outweigh their benefits?

Macedo and Lee, longtime political science professors at Princeton University, hold that the answer to the first question is almost certainly no. Although “governments had never previously been able to stop a respiratory pandemic,” public health officials came to embrace a strategy that “presuppose[d] the impossible: that the United States could suppress the spread of Covid.” This approach ignored the “dominant view” among public health experts prior to COVID that NPIs “were of limited use” in responding to “a respiratory pandemic.” In fact, “[n]o Western plans for a respiratory pandemic available at the outset of the Covid pandemic recommended sweeping NPIs such as large-scale quarantines, lockdowns, preemptive school closures, and mass testing and contact tracing.” In Covid’s Wake’s early chapters are an account of how and why the experts so quickly reversed themselves on NPIs.

***

The authors emphasize how American federalism allowed for significant variation at the state level in COVID policies. In the American system the states, not the federal government, possess the general “police power” over health and safety. State governments—almost always governors—decided whether to require residents to stay at home or wear masks, and whether to close schools and businesses. Though nearly all adopted these policies, variation across states was considerable. For example, Governor Gavin Newsom of California, the first to impose a stay-at-home order, kept his in place for over 150 days; New Mexico’s governor Michelle Lujan Grisham kept hers for just under 250 days. No other state went longer than 100 days and seven states issued no such orders at all. Likewise, public school closures, which were universal by March 25, 2020, lasted only until the summer break in some states and a full year longer in others.

Did these NPIs save lives? Not according to the data that Macedo and Lee present. They show that death rates were unaffected by the number of days it took for a state to impose its first stay-at-home order, the number of days the stay-at-home order remained in effect, and the number of days that schools were closed. As for the vaccines, the authors found that states with higher rates of vaccinations had lower rates of COVID deaths: “Variation in vaccination rates can account for fully 47 percent of the state-by-state variation in Covid mortality.”

A later chapter reviews the evidence of the effectiveness of mask wearing. In February and March of 2020 such authorities as Dr. Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID); the U.S. Surgeon General; and the World Health Organization all advised against mask wearing by the public to combat the spread of COVID. In early April, The Washington Post “echoed the pre-Covid conventional wisdom” in a headline: “Everyone Wore Masks during the 1918 Flu Pandemic. They Were Useless.” In January 2023, after the pandemic had largely run its course, a Cochrane Library study—the gold standard for systematic reviews of medical research—found no evidence that masks, including high-quality N-95 masks, reduced COVID deaths.

As Macedo and Lee write in their conclusion, “it became clear to anyone who cared to look” that the strategy to contain the spread of the virus was not working, and “[s]tates and regions with lighter restrictions were not faring systematically worse than those with more stringent restrictions.” Yet the public health establishment and national policymakers seemed uninterested in learning from the array of experiments being conducted in the nation’s 50 “laboratories of democracy.” In this respect, write the authors, the COVID pandemic “offers a sobering failure of the laboratories of democracy idea.” Policymakers should have learned from the state comparisons but did not: “decision-making about pandemic policy was rigidly ideological and moralized,” and, thus, did not “pragmatically adjust to new information and experience.”

***

Though it seems true that national policymakers did not learn much from state-by-state comparisons, it is less clear that this was the case for state policymakers. For example, after California issued a stay-at-home order on March 19, 2020, 42 other states followed (all by April 7), but seven—Arkansas, Iowa, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota, Utah, and Wyoming—never issued such an order, even as the virus spread throughout the country. Why did these states refrain from adopting a policy that was embraced by 43 other states? Similarly, why did nine states rescind their stay-at-home orders by the end of April, and another 14 by mid-May? Did these states remain unconvinced that stay-at-home orders across the country were slowing the spread of the virus? Was this the “laboratories of democracy” living up to their promise?

Macedo and Lee note that “Democratic-leaning states had the most stringent Covid restrictions across the spring, summer, fall, and winter of 2020, and Republican-leaning states had the least stringent restrictions throughout that period.” Why was this? In general, the authors attribute these policy differences to variations in public opinion in these states, with governors more or less accurately reflecting the views of their citizens. Were Republican citizens and officials more suspicious of government mandates and, concomitantly, more committed to economic and personal freedom? This may have inclined them to be less ideological and moralistic about COVID policies and, thus, more open to what could be learned about the effectiveness of government-imposed restrictions across the states. To what extent, for example, did other Republican governors learn from the success of Florida’s Ron DeSantis in pushing back against mask mandates and extensive school and business closures?

In a larger sense, In Covid’s Wake itself vindicates federalism’s “laboratories of democracy” idea. Imagine looking back at COVID policies dictated entirely by the federal government, with, as a result, no state-by-state variations. How much harder would it be to assess whether stay-at-home orders, school closures, and other COVID restrictions had any effect on deaths due to COVID? With their state-by-state data, the authors make a convincing case that NPIs did not slow the spread of the disease or reduce deaths from it. There is, of course, no guarantee that when the next pandemic hits, we will consult the lessons of COVID to guide our response. But if we do try to learn from the past, we will have no better place to look than the successes and failures of the different states during the COVID crisis of 2020-23.

***

It would be indictment enough of COVID policymaking if our governments unnecessarily imposed widespread restrictions on human freedom and then failed to modify or end such restrictions when evidence demonstrated their ineffectiveness. But it was worse than this, for the policies themselves carried undeniable and substantial health, economic, and social costs—costs that were simply ignored by policymakers and public health officials.

For Macedo and Lee, “one of the most striking features of Covid policymaking” was this “[i]ndifference to weighing the expected costs of pandemic control policies against their expected benefits.” Life is full of trade-offs, and it seems an elementary point that when proposing policies to achieve certain social benefits, one must consider the costs imposed by the policies themselves and determine whether the anticipated benefits outweigh the perceived costs. Failure to consider both costs and benefits, the authors write, “constitutes a fundamental failure of democratic deliberation.” Yet, in 2020-21, “consideration of trade-offs was systematically swept aside.”

The public health experts most responsible for directing national COVID policy all embraced an extremely narrow understanding of the policies’ purpose. Fauci acknowledged that he did not see it as his job “to consider the economic costs or other ‘potential negative consequences’ of Covid policy.” Dr. Deborah Birx, who was brought in to coordinate COVID policy in the White House, saw her job strictly as “reduc[ing] disease-related fatalities.” She “simply could not tolerate the notion…[that] even 0.1% of Americans die a preventable death.” As the authors put it, “under Birx’s view, preventable deaths must be prevented, regardless of cost.” (It would be like asking a transportation engineer to design a highway system with the single goal of reducing deaths from traffic accidents. So much for left turns, or speed limits much above 30 miles per hour.) And Fauci’s boss, Francis Collins, then-director of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), now admits that he gave no consideration to the costs of COVID policies. As he said in 2023 of the “public health mindset” that he embraced, “You attach infinite value to stopping the disease and saving a life. You attach a zero value to whether this actually totally disrupts people’s lives, ruins the economy, and has many kids kept out of school in the way that they never quite recover from.” It’s scarcely believable that the person at the top of the $45 billion agency devoted to promoting the nation’s public health could hold such a view. If this were not bad enough, the media and academics joined the public health establishment in ignoring, or denying, the collateral costs of COVID policies.

***

And, indeed, the costs of COVID policies—including costs to physical and mental health—were considerable. Among others recounted by Macedo and Lee: “cancer screening declined drastically”; excess deaths from heart disease, diabetes, Alzheimer’s, overdose, and homicide all rose; obesity increased, especially in children; anxiety, depression, and eating disorders all increased, as did “pediatric emergency department visits for self-harm, suicidal ideation, and attempted suicide”; substance abuse rose; and people in nursing homes and long-term care facilities were deprived “of meaningful human connections, personal well-being, and quality of life.” One might think that public health professionals would care about such costs and not assign them a value of “zero.” The authors report that in May 2020, COVID task forces advising decision-makers in 24 countries had “mainly virologists and epidemiologists” but largely no “specialists in areas such as mental health, child health, chronic diseases, preventive medicine, gerontology, not to mention experts in non-health spheres.”

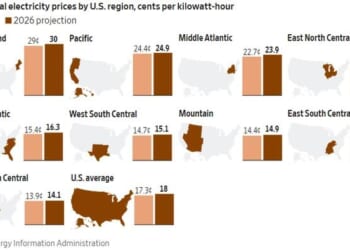

What, then, of the non-health costs imposed by COVID policies? Congress authorized $5 trillion in new spending, with most of it going to compensate individuals and businesses for the income lost by COVID policy restrictions. The “massive aid packages,” together with disruptions in supply of goods, led to “sharply elevated levels of inflation, a dramatic reversal of the low inflation environment prevailing for many years before 2020.” Businesses closed and unemployment skyrocketed, especially harming “low-wage, service-sector workers.” More broadly, “nearly every aspect of the pandemic response inflicted greater harms on economically disadvantaged people.” For the first time in American history, “public schools were closed wholesale in an effort to preempt the spread of a novel infection.” It is hardly surprising that school closures resulted in “major declines in student learning.” Even more, after schools reopened there was a doubling of “chronic absenteeism from school.”

***

Macedo and Lee conclude their summary of the costs of COVID policies with a poignant paragraph about “the sheer reality of lost time”:

The time lost with aging parents and grandparents, including holidays in 2020, the last Thanksgiving or Christmas for many; lost ceremonies and commemorations (graduation 2020; Zoom retirement parties); canceled school plays; lost sports seasons for young athletes who will never get those youthful days back…. Lost connections—new friends that students would have made in person, lost loves never met in chance encounters, forgone travel. Even teleworking members of the laptop class lost connections with work colleagues—collaborations that never happened, new ideas no one ever had because the conversation that would have sparked them never took place. The policy response to the Covid pandemic reshaped lives; indeed, it reshaped all of our lives, often in profound ways.

It might not have been possible for decisionmakers to factor in the costs associated with “lost time.” The same cannot be said about massive new federal spending and the inflation it engendered, the business closures and job losses that affected those not fortunate enough to be able to work from home, and the steep declines in student learning. Yet, consideration of these costs, as well as the physical and mental health costs outlined above, played no role at all in formulating the government’s COVID policies. What is especially dismaying is that pre-pandemic planning in the public health community had “correctly anticipated many of the costs and ethical dilemmas that emerged during the Covid pandemic response.” COVID policymaking, Macedo and Lee aver, was nothing less than a “failure of democratic deliberation.”

***

One might think that the authors would end their account here. Instead, in their final chapters they warn of deeper pathologies in American democracy that the COVID crisis revealed and that portend serious problems in the future. One is the politicization of science. Macedo and Lee describe the efforts by leading scientists in February and March of 2020, including Dr. Fauci, to deceive the public into believing that the virus must have come from natural processes involving a jump from bats to humans through some intermediary species sold at the Wuhan seafood market. Yet from the very beginning, key scientists believed that the evidence supported an alternative theory: that the virus, originally from bats, had been manipulated in the Wuhan Institute of Virology to be able to infect humans and had accidentally leaked from the lab. Such “gain of function” research, though highly controversial, was defended as a proactive measure to allow scientists to develop vaccines in advance of a possible epidemic. Macedo and Lee show, through the growing public record of communications among the key players, that scientists intentionally distorted what was known about the virus and managed to relegate the lab-leak hypothesis to “conspiracy theory” status.

Why would scientists do this? In Covid’s Wake suggests two possible reasons. First, some apparently believed that if the virus were known to have been manipulated at a Chinese lab, a major international incident might result—up to and including war. Others may have “lacked faith in President Trump’s ability to manage such a crisis.” And there were genuine fears that the Chinese government, if found to have tolerated unsafe conditions at the Wuhan lab, might refuse to cooperate with the international scientific community. But Macedo and Lee insist that even if these judgments were sound, “[t]hese were not, however, scientific judgments” (emphasis in the original), but rather political judgments to be made by public officials. “Is it consistent with the governing principles of democracy or science,” they ask, “to entrust scientists in closed and secretive sessions to make such policy judgments unilaterally? We think not.”

The authors also show that less high-minded motivations were likely at work. Consider Dr. Kristian Andersen of the Scripps Institute in San Diego. In late January 2020, when the novel virus first became known to American scientists, Andersen believed that it had “properties that may have been genetically modified or engineered.” A few days later, he wrote to Fauci that he and three other scientists believed the virus “look[ed] engineered” and found “the genome inconsistent with expectations from evolutionary theory.” According to testimony he later gave to Congress, Andersen repeated his concerns in a conference call with American and European virologists on February 1. Three days later, he wrote to a colleague that “the lab escape version of this is so friggin’ likely to have happened because they were already doing this type of work and the molecular data is fully consistent with that scenario.” Yet, within weeks, Andersen was the lead author of the now-famous “Proximal Origin” paper, published online in February and then in final form in Nature Medicine in mid-March. It concluded that “[o]ur analysis clearly shows that SARS-CoV-2 is not a laboratory construct or a purposefully manipulated virus.” At a press conference, Andersen said, “We can firmly determine that SARS-CoV-2 originated through natural processes.” We now know that just days before the paper went online, Andersen had emailed the senior editor at Nature that he and his colleagues could not “refute a lab origin and the possibility must be considered as a serious scientific theory.” The “Proximal Origin” paper “was highly influential in shaping the narrative around Covid’s origin.” By July of 2023, “it had been accessed nearly six million times.”

***

Macedo and Lee hold that the paper misrepresented, apparently intentionally, the state of the science: that “the headline-grabbing claims in the article are not supported by the evidence presented in it.” (Later, the authors cite congressional testimony from 2024 by Professor Richard H. Ebright, the head of a research laboratory at Rutgers University, who concluded that there was an “extremely strong case” that the COVID virus had “a research-related origin” and that there was “compelling evidence” that the “Proximal Origin” paper was “a product of scientific misconduct, up to and including scientific fraud.”) Fauci, Collins, and others trumpeted the paper’s “findings” as settling the issue of the origins of the virus. The chief editor of Nature Medicine urged others to put aside “conspiracy theories” about the virus’s origins and to stop spreading “misinformation.”

Within a few weeks, the authors write, “Andersen’s lab received a $1.9 million grant from Fauci’s NIAID.” Although peer review of the grant application had been completed months earlier, “final approval was pending as Fauci and Collins oversaw the effort of Andersen and his co-authors to deflect responsibility from the lab that NIH and NIAID were helping to fund.” This points to “the vast power wielded by Collins, Fauci, [Dr. Jeremy] Farrar [director of the Wellcome Trust in London], and the agencies they headed as the world’s mega-funders of health-related research.” It is hard to make sense of Andersen’s contradictory positions during this first month after COVID became known to U.S. scientists unless he felt some great pressure to conform to Collins’s and Fauci’s preferred natural origins hypothesis. It is reasonable to believe that a $1.9 million government grant would constitute such pressure.

***

But why would it matter to Fauci in particular, especially so early in the pandemic, whether the virus was produced by nature or by a researcher in a lab? Either way, it presents the same public health problem for the nation and the world. Macedo and Lee show that Fauci “had long supported gain-of-function research of the sort done by the Wuhan institute of Virology.” He had even co-authored an op-ed with Collins (and another virologist from NIAID) in The Washington Post in 2011 that defended gain-of-function research. Though the op-ed did not use that term, it explicitly endorsed “generating a potentially dangerous virus in the laboratory” if this could be done safely and could help researchers develop vaccines, or other counter-measures, in advance of a possible natural evolution of the virus. As the title of the op-ed announced, this was a “risk worth taking.” More importantly, “Fauci’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases funded gain-of function research in the Wuhan lab, through grants to the EcoHealth Alliance, which used the Wuhan Institute as a subcontractor.” If Fauci had forgotten that fact in the early weeks of the pandemic, he was reminded of it by one of his top staffers in a memo on January 27, 2020, “two hours before he was to appear at a White House news conference and just days before initiating the conference call that led to the writing of ‘Proximal Origin’ and what now appear to be efforts to suppress open inquiry concerning Covid’s possible lab origins.”

Yet, in congressional testimony and other public statements Fauci has adamantly denied that his agency funded gain-of-function research at the Wuhan lab. Most memorably, he did so in widely viewed and fiery confrontations with Senator Rand Paul in Senate hearings. Fauci seems to have made up his own definition of gain-of-function. In congressional testimony in May 2024, the principal deputy director of NIH confirmed the standard definition that research was gain-of-function if it involved “enhanced pathogenicity and/or transmissibility” of a virus. But Fauci claims that research is gain-of-function “only if it is ‘likely highly transmissible and capable of wide and uncontrollable spread’ among humans and is ‘highly virulent’ or deadly.” “In other words,” write Macedo and Lee, “only the worst imaginable killer viruses count.” Fauci, of course, had powerful reasons for engaging in such deception; for the “reputations [of Fauci, Collins, and others] were very much on the line should the Covid pandemic be found to have spilled over from gain-of-function research.” When Fauci left government at the end of 2022, he “retired to media acclaim—from the same news outlets that stigmatized the lab leak theory as a conspiracy theory and that have not yet (as this book goes to press) adequately investigated the question or their own previous handling of it.”

***

Perhaps news outlets are now coming to grips with the massive public deception perpetrated by scientists about COVID’s origins and their own complicity in it. In March 2025, The New York Times ran a lengthy opinion piece by frequent contributor and Princeton professor Zeynep Tufekci. Under the title “We Were Badly Misled About the Event That Changed Our Lives” and relying on information that had come to light through congressional investigations, leaks, and Freedom of Information requests, Tufekci recounts how “some officials and scientists hid or understated crucial facts, misled at least one reporter, orchestrated campaigns of supposedly independent voices and even compared notes about how to hide their communications in order to keep the public from hearing the whole story.” On the last point, she reports that “David Morens, a senior scientific adviser to Fauci at the National Institutes of Health, wrote to [Peter] Daszak [the president of the EcoHealth Alliance] that he had learned how to make ‘emails disappear,’ especially emails about pandemic origins. ‘We’re all smart enough to know to never have smoking guns, and if we did we wouldn’t put them in emails and if we found them we’d delete them,’ he wrote.” Not only did “public health officials and prominent scientists” suppress evidence of a lab leak and grossly overstate the case for a natural origin, they, and others, treated those who speculated about a leak from the Wuhan lab as “kooks and cranks” and conspiracists.

Tufekci agrees with the current assessments of the CIA, the FBI, and the Department of Energy that “a lab leak…[was] the likely origin” of the COVID pandemic. She reports that German officials had reached a similar conclusion very early on, and she asks a highly pertinent question: “Why did it take until now for the German public [and the world] to learn that way back in 2020, their Federal Intelligence Service endorsed a lab leak origin with 80 to 95 percent probability? What else is still being kept from us about the pandemic that half a decade ago changed all of our lives?”

Tufekci’s purpose is not simply to help to correct the historical record, but to call attention to the dangers of the kind of research conducted at the Wuhan lab. She reports the lab did not employ “the very highest safety protocols”—protocols that, according to two experts on coronaviruses she quotes, are “insufficient for work with potentially dangerous respiratory viruses.” She concludes that if the COVID pandemic resulted from a lab leak, “that would mean two out of the last four or five pandemics were caused by our own scientific mishaps.”

***

The campaign of public deception about COVID’s origins had the effect of deflecting public and government attention away from the dangers of gain-of-function research. Scientists circled the wagons around the EcoHealth Alliance in 2020 when, after it lost a grant to conduct research into bat viruses at the Wuhan Institute, “no fewer than 77 Nobel laureates and 31 scientific societies lined up to defend the organization.” Here is how The New York Times covered the story on May 21, 2020: “The group [EcoHealth Alliance] collaborated with the Wuhan Institute of Virology, which has been at the center of conspiracy theories about how the novel coronavirus originated. Virologists and intelligence agencies agree that the virus evolved in nature and spread from animals to humans.” Well, as In Covid’s Wake convincingly demonstrates, scientists in January and February of 2020 certainly did not agree that the virus evolved from nature rather than accidentally emerging from the Wuhan lab. The Times coverage is testimony to the effectiveness of the secret campaign by the nation’s highest public health officials, and scientists in league with them, to allow only one possible explanation for the origins of the virus. By labeling the alternative a “conspiracy theory,” The New York Times, and myriad other news organizations, saw to it that no other explanation would be tolerated in the public sphere.

***

What’s more, the larger scientific and academic establishment would not tolerate dissent on either the origins of the virus or the restrictive policies imposed to confront it. This is illustrated by the reaction of Collins, Fauci, and others to the Great Barrington Declaration of October 2020 and by the efforts of Stanford University faculty to censure Dr. Scott Atlas, M.D., of Stanford’s Hoover Institution. The two cases are now well known, and ably recounted by Macedo and Lee.

In the first case, three “distinguished academics” with highly relevant expertise—Dr. Martin Kulldorff of Harvard, Dr. Sunetra Gupta of Oxford, and Dr. Jay Bhattacharya of Stanford—met in the town of Great Barrington in western Massachusetts and formulated a recommendation, which they published online on October 4, to alter prevailing COVID policies by focusing protection on the elderly and the most vulnerable while allowing businesses, sporting events, and schools to open. “Current lockdown policies,” they insisted, “are producing devastating effects on short and long-term public health…leading to greater excess mortality in years to come.” Eventually, “thousands of ‘medical and public health scientists’ signed the Declaration” as did “nearly fifty thousand medical practitioners.” (After his nomination by President Trump and confirmation by the Senate, Bhattacharya became the director of the NIH on April 1, 2025.)

Back at the NIH, the reaction was immediate. Within days of the Declaration’s publication, Director Francis Collins emailed Fauci and others denouncing it as the product of “three fringe epidemiologists” (though, as he acknowledged, it was also co-signed by “Nobel prize-winner Mike Leavitt at Stanford”) and urging “a quick and devastating published take down of its premises.”

Denunciations of the Great Barrington Declaration promptly appeared in Wired and The Nation, the latter written by Gregg Gonsalves, an associate professor of epidemiology at the Yale School of Public Health. Oddly, just six months earlier, Gonsalves had “rallied more than eight hundred public health scholars and scientists…to sign an open letter warning of the costs of lockdowns, school closures, and travel bans.” (One of the recurring themes of In Covid’s Wake is how quickly and radically public health officials and other scientists reversed their positions on both purely scientific questions, such as the origin of the COVID virus, and the larger public policy issues about how best to respond to the pandemic.) Other denunciations of the Great Barrington Declaration soon followed.

For Collins, then, it wasn’t enough to assign a value of “zero” to the health and other deleterious effects of COVID policies. It was necessary also to shut down any dissent at all, and certainly any larger public debate, on COVID policies. To the best of my knowledge, Collins never denied the charge in the Great Barrington Declaration that the shutdown policies had resulted in “lower childhood vaccination rates, worsening cardiovascular disease outcomes, fewer cancer screenings and deteriorating mental health”—not to mention the economic, educational, and social effects of closing businesses, schools, and sporting events. Whether these effects were real, whether they were substantial, and whether they might outweigh the benefits of shutdowns—none of this was to be debated.

***

The case of Dr. Atlas is a chilling example of academic suppression of dissent on COVID policies. A fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution, Atlas specializes in radiology and is the author of five books on health care policy. In late April 2020, Atlas published an opinion piece in The Hill that challenged lockdown policies on many of the same grounds later detailed in the Great Barrington Declaration. He reiterated these points in appearances on Fox News. President Trump brought him into the White House as an adviser in July 2020, where he served through November 2020.

Soon after Atlas went to the White House a campaign began to discredit him. “Ninety-nine Stanford University professors of epidemiology, immunology, and public health published an open letter condemning their colleague.” They claimed that “[m]any of his opinions and statements run counter to established science,” that he had “undermin[ed] public-health authorities,” and that he had spread “falsehoods and misrepresentations of science.” Strikingly, “[t]he page-and-a-half letter cited none of Atlas’s writings or statements nor any scientific research.” Macedo and Lee report that after the letter appeared, “Dr. Martin Kulldorff offered to debate any of the signatories but had no takers.” Then in November, the Stanford University Faculty Senate voted to censure Atlas for advocating “a view of COVID-19 that contradicts medical science.” According to The Stanford Review (November 25, 2024), Atlas had been given no “opportunity to defend his positions” before the censure was issued. And in November of 2024, “[e]ven as evidence…mounted supporting many of Atlas’s positions,” the Faculty Senate voted against repealing its 2020 censure.

***

Macedo and Lee charge Atlas’s Stanford critics with two offenses: refusing to engage “on the point that anti-Covid policies entailed harms of their own,” thus “begg[ing] all the relevant questions,” and seeming to hold “that pandemic policy should be made by people with narrow scientific expertise.” For the authors, the latter position is nothing less than “absurd”: “Such experts should inform decision-makers, but their expertise is far too narrow to provide a sound basis for policy affecting the whole of society.” Scientific experts are in no position to assess the “complex array” of “value judgments and trade-offs across alternatives, numerous social and economic considerations, and highly uncertain predictions about human behavior.”

Even more ominous than academics censoring their own for deviating from the approved party line was government actively urging social media companies to censure opposition to official policy. In Covid’s Wake highlights “extraordinary restrictions on free speech” that came with the “mobilization against Covid.” So extensive were these restrictions that “[i]n the summer of 2023, a federal judge characterized this effort as the biggest campaign of government censorship in U.S. history.” Through disclosures in a court case brought by Kulldorff and Bhattacharya, we now know that the White House, the Centers for Disease Control, the FBI, and other federal agencies “were deeply involved in social media censorship activities.” No opposition was beyond the reach of the censors. At one point, YouTube removed a video of an official public hearing in Florida where Governor DeSantis and the authors of the Great Barrington Declaration discussed COVID policies. Another platform even removed “a video of counsel for the state of Louisiana complaining about being censored.” Remarkably, the federal government was urging the private sector to censor deliberations by state and local governments about COVID policies that were mainly the province of those state and local governments. This is wrong in so many ways.

***

In an incident reported by journalist Matt Taibbi in March 2023 (not covered in In Covid’s Wake), something called the Stanford University Internet Observatory urged social media companies to suppress “[t]rue content which might promote vaccine hesitancy,” such as “viral posts of individuals expressing vaccine hesitancy, or stories of true vaccine side effects.” The Observatory even urged the suppression of “true posts” of “individual countries banning certain vaccines,” lest such information “fuel [vaccine] hesitancy.” I am not aware of a comparable example in the history of the country of an arm of an American college or university expressly calling for the suppression of truth in the public sphere. Stanford’s Internet Observatory, it may be hard to believe, titles its periodical publication “Journal of Online Trust and Safety”—as if suppressing the truth on social media will enhance public trust in the truth of the content of social media.

Perhaps most alarming to the authors—as it should be to all of us—is the “authoritarian technocracy” that the COVID episode portends for our future. “[T]he Covid crisis,” Macedo and Lee conclude, “revealed a troubling alignment of the scientific establishment and political elites to employ technology to prevent the proliferation of error—as they defined it, under an always-shifting definition of truth.” These elites have even come up with three new terms to describe information or views with which they disagree: “misinformation,” “disinformation,” and “malinformation.” “Indeed,” write the authors, “one need not be George Orwell to find suspicious the proliferation of new terms for what is, essentially, erroneous information.” Increasingly, educated elites have come to believe that “social and political institutions” need “greater control of information…to combat error.” In a word, the people must be shielded from exposure to “error,” as defined by their betters.

One way to do this is to discipline physicians who spread COVID “misinformation,” as called for in an article that appeared in August 2023 in a journal of the American Medical Association. The article identified five examples of COVID “misinformation”—a) that “[t]he virus originated in a lab in China”; b) that government officials withheld Covid information from the public; c) that “the effectiveness of masks” was doubtful; d) that natural infection and recovery were as effective in contributing to herd immunity as the vaccines; and e) that government officials pressured social media companies to censor COVID-related information—all of which, Macedo and Lee claim, “may actually be correct, or, at minimum, within the scope of reasonable disagreement.” More pointedly, most of the five statements were almost certainly true. So, as with Stanford’s Internet Observatory, no statements that challenged the orthodoxy, even if true—perhaps especially if true—were to be allowed. And in this case, violations might bring career-ending reprisals for doctors who challenged the orthodoxy.

***

“In sum,” write Macedo and Lee, “Covid policy furnishes a window onto trends in scientific and journalistic practices, and the public culture more broadly, that need far more critical attention.” “Most troubling” is the fact that “elites now assert the need for control over the spread of ‘misinformation.’” But, the authors insist, “placing unchecked power to define ‘error’ in the hands of elites in government and the scientific establishment would be a grave error, incompatible with liberalism, science, and democratic self-government.”

With In Covid’s Wake, Stephen Macedo and Frances Lee have written a brave and wise book about scientific misbehavior, the utter failure of officials to consider the impacts of their policies on the American public, the manipulation of public opinion by stoking fear and censoring opposing views, the complicity of the media and the academy, and the corruption of public deliberation. The nation paid a high price for this dysfunction, but it may pay an even greater one in the future if the dangerous trends revealed during the COVID crisis go unchallenged.