We’d appreciate your input on a few questions about environmental and energy policy. This brief survey should only take one minute to complete.

Your responses will help us better understand different perspectives on these important issues. All responses are confidential.

Welcome to Dispatch Energy! The intensity of the news cycle nowadays means that longer-term perspectives on energy can be overshadowed by unfolding events—Venezuela! Iran! Two-dollar gasoline!

Energy markets, policies, and technologies do of course respond to daily events, but they also evolve over years and decades. We use scenarios—representations of plausible futures based on current understanding—to shape our thinking about how today connects to tomorrow. Scenarios are not predictions of the future, but offer ways to explore the implications of what we currently believe about how the future might play out.

For decades, the International Energy Agency (IEA) has played a key role in producing such projections. And although the agency’s models have not been free from criticism, such criticism reflects the importance of using these scenarios as a baseline for debating both where we appear to be headed and where we’d collectively like to go.

Today, I highlight five figures from the IEA 2025 World Energy Outlook (WEO) that embody key assumptions worth paying attention to as we move into the future.

- Pay attention to projections of future population growth.

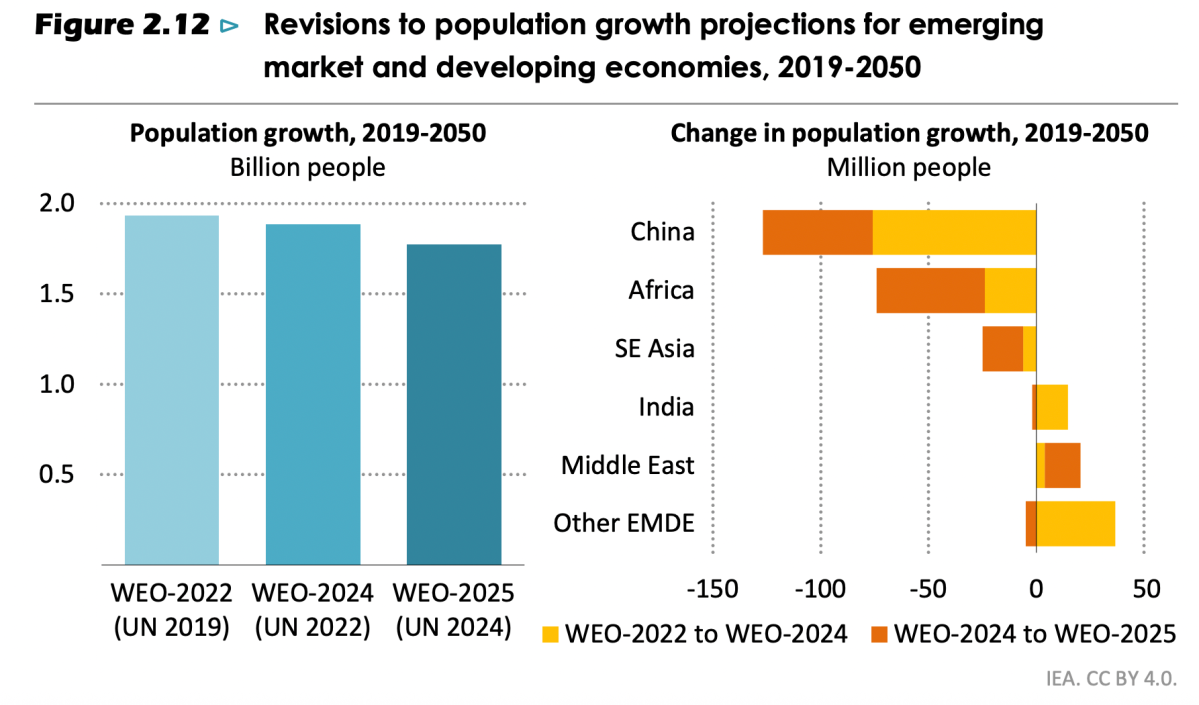

These graphs from the IEA 2025 WEO are remarkable. They show that in just one year, from 2024 to 2025, projections of the global population in 2050 dropped by about 100 million people, based on United Nations estimates, with most of the decrease in Asia and Africa.

The reduction in expected population is now a trend, with each year’s updated projections showing a smaller expected population than the last. It also appears that the trend is accelerating due to rapidly falling birth rates around the world, for reasons that are not yet fully understood.

If downward revisions for global population continue, the pattern will have significant implications for energy and also the broader economy.

- Energy demand is going up, by a lot.

The graphs above show that global energy demand is projected to increase significantly by 2050. Of note, all of this increase occurs outside of Japan, Korea, North America, and the European Union.

In contrast, some experts project that demand for electricity in particular will increase dramatically in regions where the IEA foresees little or no growth. For example, consultancy ICF expects U.S. peak electricity demand to grow 14 percent by 2030 and 54 percent by 2050. Deloitte similarly predicts U.S. peak demand to grow 26 percent by 2035. The IEA and these groups cannot both be correct.

Just as population growth projections may be trending lower over time, projected demand for energy may be trending higher. We should also pay attention to the degree to which demand may or may not depend upon overall population. It is possible to envision a world with fewer people than previously expected, with a mid-century peak in population, but with higher energy demand regardless.

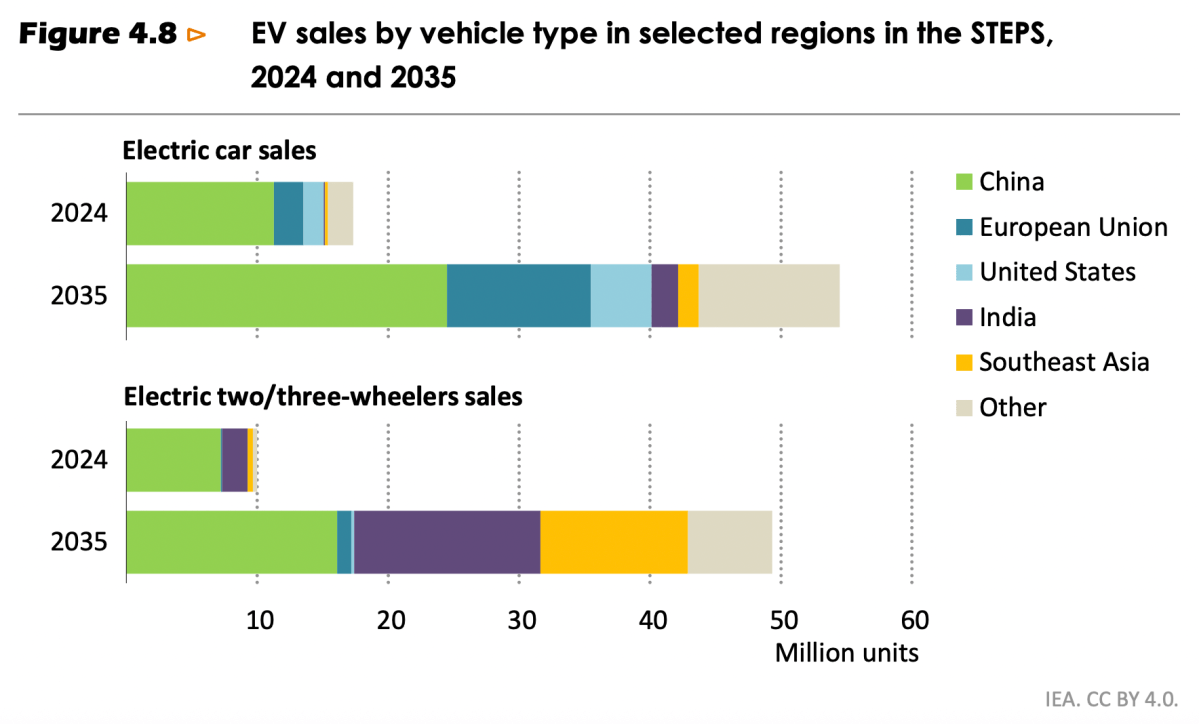

- Electric vehicle adoption is projected to increase dramatically.

This figure shows that the use of electric vehicles is projected to rise dramatically around the world, with the vast majority of the increase expected to occur outside the EU and U.S. The increase in projected sales of two- and three-wheelers (think motor scooters and tuk-tuks) approaches 50 million per year in 2035.

These assumptions have considerable implications for the consumption of liquid fuels, and even small changes in the projections of EV adoption could lead to ripple effects across other projections, such as demand for liquid fuels. Consider that U.S. gasoline consumption has not increased over the past two decades, and has decreased over the past decade. As an analogy, consider that the U.S. saw “peak horse” in 1915 with more than 20 million horses, and by 1950, that number had plummeted to just 5 million. The lesson is that when technology advances, change can occur much faster than previously assumed.

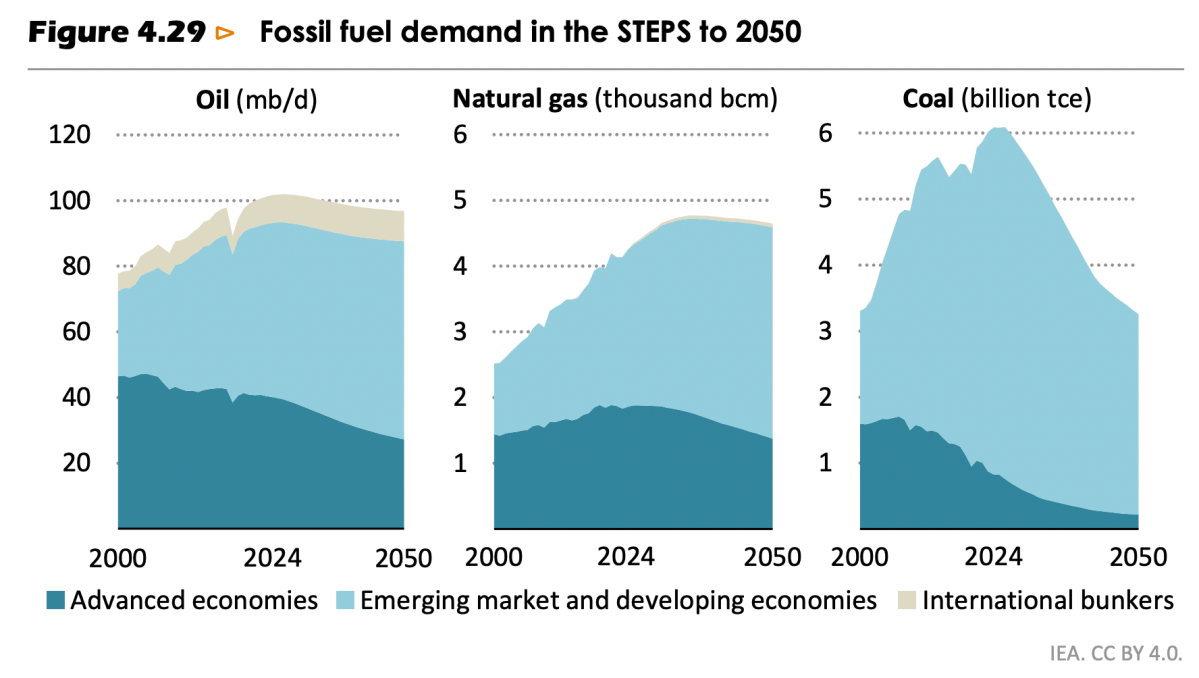

- Fossil fuels are here to stay.

The charts above show that the IEA expects consumption of oil and natural gas to plateau in the coming years and slowly decline to 2050. In contrast, coal is projected to have a sharper peak and decline, but revert to 2000 levels by 2050.

When the IEA first projected in 2023 that global demand for fossil fuels would peak this decade, much attention was paid to the notion of peak rather than what the agency expected would be a steep rate of decline afterward. The IEA has since relaxed those assumptions of a rapid decline following considerable criticism.

Whether or not fossil fuels peak in the near term, the larger context here is that fossil fuels are here to stay for much of this century under the IEA’s projections. Even so, the agency projects global temperatures to increase by less than 3 degrees Celsius by 2100, which is in line with other projections.

Expectations of a rapid transition off of fossil fuels are not supported by the IEA’s estimates, nor are rapid increases in fossil fuel consumption, as foreseen by others, particularly the scenarios that underlie much of climate science and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Whether fossil fuel consumption goes up, down, or plateaus will make a big difference for projected climate change.

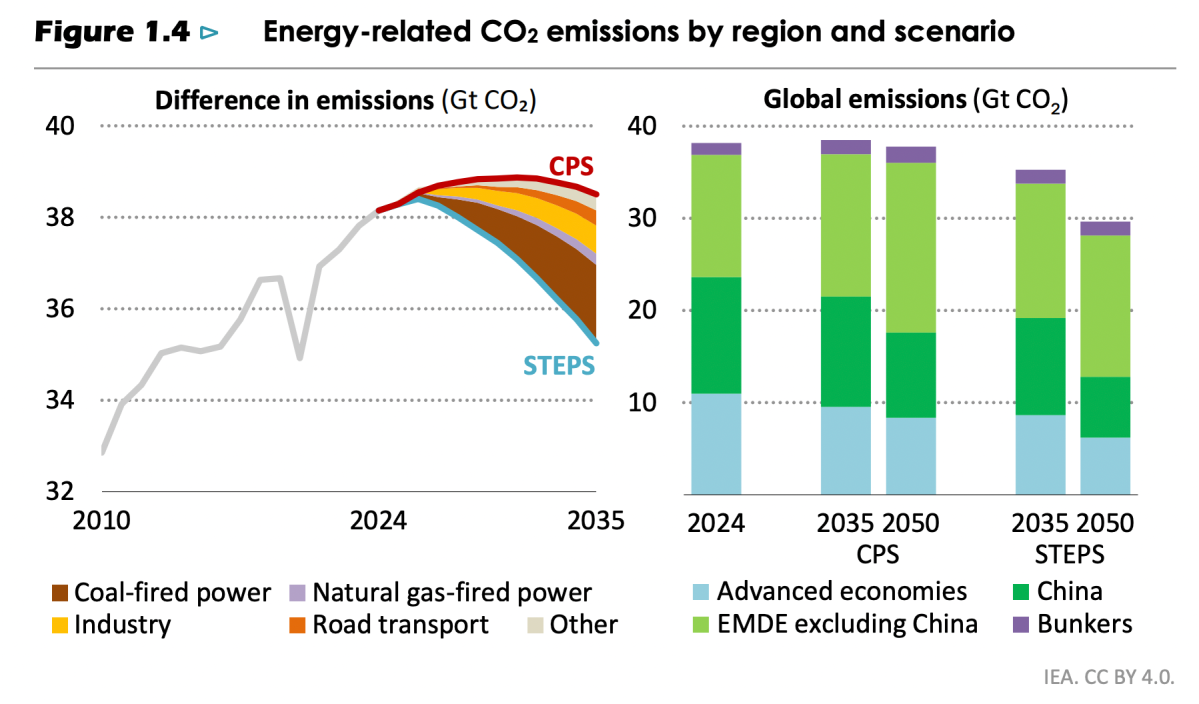

- Should the world actually decide to more rapidly reduce emissions, cutting coal consumption offers the single biggest opportunity.

These graphs show clearly that coal-fired power offers the single biggest opportunity to reduce emissions faster than projected. In the left panel of the figure above, the largest “wedge” of projected emissions reductions is the brown wedge representing coal-fired power.

Consider that one study estimated that just 150 coal power plants (5 percent of the 3,000 plants examined) were responsible for some 25 percent of all carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuels. Replacing these plants with natural gas would cut emissions from these power plants in about half, and nuclear replacement would just about eliminate them. Most of these plants are in Asia, but some are also in Eastern Europe.

The IEA WEO 2025 is wickedly complex. However, it shows that there is low-hanging fruit for rapid and deep reductions in emissions.

Small Town Versus Activist Group’s ‘Citizen Suit’

Last November, Tennessee Riverkeeper—an environmental activist group—filed a “citizen suit” against the small town of Luttrell, Tennessee, alleging that the town’s wastewater facility exceeded the limits of its discharge permit.

Facing potentially years of litigation, the town of just over 1,000 could’ve offered to settle—as others have done when facing the group’s wrath. Instead, it chose to fight back, securing a resounding victory in just weeks.

Policy Watch

- Last week, the Trump administration announced plans to withdraw the United States from 66 international organizations, including the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the latter of which was established under the auspices of the U.N. Environment Program and the World Meteorological Organization. While much attention is rightly paid to climate change at these forums, they’re also important venues for discussions on global energy policy. Of note, the IPCC has for decades overseen the creation of energy production and consumption projections that are applied in settings far beyond climate policy. I have argued that the U.S. abandons these forums at some risk to its own interests.

- The Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air, a Finnish nonprofit, released a report assessing that India’s coal-fired power generation fell by 3 percent year-over-year in 2025. The drop marks only the second full-year decrease in at least half a century, with the other occurring during the COVID pandemic. The report argues that the coal decline is the result of a few different factors, including policy-driven upticks in electricity capacity, with solar, wind, and small-hydro capacity increasing by 42 gigawatts in 2025. The other factors were milder weather, necessitating less air conditioning, and a slowdown in overall demand growth. India is one of the world’s largest consumers of coal, and it remains to be seen whether 2025 is the start of a more significant trend or an anomaly. Some argue that India’s economic growth may be accelerating, which would create increasing demand for electricity and possible increases in coal consumption.

Innovation Spotlight

- Much has been said about AI’s role in driving electricity demand. However, a much larger source of rising global demand is the expected increase in the demand for cooling. Increased demand for air conditioning, particularly in regions that today have very little air conditioning, will lead to increased demand for electricity, but it also offers a major opportunity for innovation in cooling technologies. The IEA estimates that air conditioners in Japan operate at twice the efficiency of air conditioners in the Middle East and North Africa.

Further Reading

- S&P Global has published a new report on copper, projecting an eye-popping “surge from 28 million metric tons in 2025 to 42 million metric tons by 2040 – a 50% increase.” The report argues that the surge in demand is driven by an expected 50 percent increase in global electricity demand, and the delivery of electricity depends upon copper. The report identifies increasing electricity demands of artificial intelligence as one factor driving this trend, but perhaps surprisingly, not as the most important factor. Other drivers include urbanization, changing building practices, the rise of electric vehicles, and the production of defense infrastructure in an era of geopolitical uncertainty.