William F. Buckley Jr., meditating on his last memory of his mother, wrote: “God’s creature. Well done, Lord. My Lord. Our Lord.”

That’s a very Buckley formulation: presumptuous in congratulating the Creator, but also devout, plain, wise, and full of gratitude. Buckley knew his popes and cardinals, and interviewed the occasional saint on his television show, but he saw God’s goodness and understood it, without any need for a theology as such, when it was put in front of him. His Catholicism was intellectual and generally orthodox, but his religious conspectus takes its title from a Unitarian hymn: “Nearer, My God.”

Nearer, my God, to Thee, nearer to Thee!

E’en though it be a cross that raiseth me.

Easy to sing. Hard to mean.

Hard, that is, if you think about it and take it seriously. One of the things that put me off of Christianity when I was young (beyond an intellectual vanity that was out of place) was that the greater part of Christian conversation and teaching, in my experience, had been intended to keep us from thinking about it too hard or taking it very seriously. Simple faith. That old-time religion. Just believe. Most of us have met That Christian—I sat next to her at my local café earlier in the week, and she was trying to convince her college-age children that there were no dinosaurs. “You have to ask yourself who pays for those studies,” she said. “I just believe the Bible.” I tried to concentrate on my eggs.

But what I wanted to tell her is that there is an interesting concurrence between certain implications of evolution and the plainest kind of Christianity. From evolution, we learn that our bodies and our behavior were shaped by natural pressures to maximize our chances of survival in ancestral conditions of radical scarcity and, hence, we could reasonably assume that at least some of our modern problems—the prevalence of obesity and anxiety, for example, in the rich, digitally saturated world—are the result of living in an environment that is radically different from the one for which we were optimized by evolution. From Christianity, we learn that man is fallen and out of step with his intended place in creation, that we have been separated from that condition for which we were fitted. And at whatever level of literalism you wish to apply to Genesis and whatever degree of sophistication you can bring to bear on your biological analysis, there is a point of commonality:

This is not the world we were made for. We are outcasts and misfits—or, if our separation is sanctified, we are pilgrims.

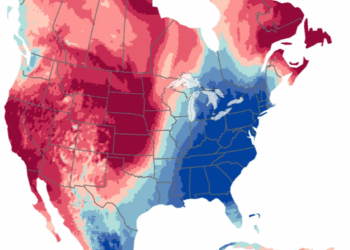

It is cold today, here at the foot of the Blue Ridge Mountains, down in the 20s in the late morning even with the sun high and bright. We had snow in early November, including a little dusting on November 11, the anniversary of the signing of the Mayflower Compact.

But we have had it easy for a while. Maybe we have forgotten what it is like to be cold. Really cold.

I do not propose to write an account of climate change today, but I will note that it used to be much, much colder around these parts. You can read in the diaries of George Washington and Thomas Jefferson about a 1772 blizzard that dumped three feet of snow on Virginia. In 1922, nearly 100 Washington theatergoers were killed when the weight of blizzard snow caused the roof of the Knickerbocker Theater to collapse—a disaster death toll that would not be matched in the D.C. area until September 11, 2001. But it isn’t all ancient history: In early November of 1987, a foot of snow fell on Virginia practically at all once, and the commonwealth’s modern transportation snow plan dates from that event.

It was a good deal colder in 1620, when our spiritual forebears signed the Mayflower Compact upon landing in Massachusetts on November 11, during a period known as the Little Ice Age. The ground was hard, there was sleet and snow, and the Pilgrims were not very well prepared for it. Subsequent winters, Pilgrim sources report, were even colder. As I have written before, I think it is worth remembering—repeating to ourselves, out loud as often as is necessary—that those trembling fanatics came here in sailboats, taking their children and only such supplies as they could carry across the Atlantic. They landed a month shy of the first official day of winter. But it was cold enough. Nearly half of the Mayflower passengers died before the winter’s end, with only about 50 of the original 102 living to see the snow melt and witness the blooming of the springtime ground laurel. (That plant, Epigaea repens, is now known as mayflower.) That suffering and brutalization was not forced upon them—they chose it.

What possibly could have?

Here is a time, perhaps, to speak of the Holy Ghost. Not the Holy Spirit. Jorge Luis Borges wrote admiringly of English’s connotational diversity: “It would make all the difference in the world in a poem if I wrote about the Holy Spirit or if I wrote ‘the Holy Ghost,’ since ‘ghost’ is a fine, dark Saxon word, when ‘spirit’ is a light Latin word.” There is something dark in the possession of the Puritans—I do not mean dark in the sense of evil, of course, but in the sense of genuinely occult, mysterious, beyond our sight, something in the shadows of that fine Saxon darkness. The Puritan polemicist Thomas Goodwin, chaplain to Oliver Cromwell, published a tract titled The Work of the Holy Ghost in Our Salvation. It makes good Thanksgiving reading:

God made and prepared a world consisting of, and filled with [a] variety of creatures, the making of which cost him six days’ work. There were delicacies of fruits for the taste, an entertainment for the eye in all sorts of colours, light, ornaments, and tapestry, which heaven and earth affordeth to this day. There was a brave world, and richly furnished, as the apostle speaks of it. The angels stood by, and wondered all the while for whom all this should be prepared, for they had not senses to be affected with them. God after all, at the latter end of his work, brings in man, and sets Adam down in the centre of this world; and lo, he had at the first of his creation an eye to see and to be taken with all the beauties God had scattered up and down throughout the whole. He had an ear to hear all the music which the melodies of birds singing, or the murmurings and warblings of rivulets, could afford. He had a taste and belly suited to take pleasure in all these varieties of fruits, or whatever else God had provided as a banquet for him; insomuch as there was not any one thing God had made but he had some sense, inward and outward, to take in a pleasure from it, or some faculty in his mind to close with and make use of it.

Whence it was apparent unto himself and the angels, the spectators, that God had first prepared and set out all these for the man, and then created the man, in like manner prepared and fitted for all these things. He had an ear and an eye (as both the prophet’s and apostle’s words are) to receive and take in what was thus made for him. Thus the apostle tells us it falls out in this new creation, God hath been from everlasting contriving and ordaining, and in the fulness of time preparing, all these glorious truths and things which the apostle to whom was committed the news and tidings of this world to come, by the Holy Ghost.

Half of them died. The rest were miserable, often sick, often hungry, often afraid. And they designated a day for thanksgiving. Again: What possessed them? What was the Holy Ghost whispering to them and showing them in their ecstacies and visions? Some of them dreamed of a new Israel, and some of them dreamed of a new Eden, well provided with “delicacies of fruits for the taste” and other good things in the New World. But all of them—these were serious men and women—knew they were landing on the shores of a savage wilderness. On the edge of winter. With what? Some hardtack, a little salt pork, a plan, and their prayers. They knew that this was a death sentence for at least some of them, likely many of them.

Why? Why do that to themselves? Why do that to their children? Why, in God’s name?

Be ye not unequally yoked together with unbelievers: for what fellowship hath righteousness with unrighteousness? and what communion hath light with darkness?

And what concord hath Christ with Belial? or what part hath he that believeth with an infidel?

And what agreement hath the temple of God with idols? for ye are the temple of the living God; as God hath said, I will dwell in them, and walk in them; and I will be their God, and they shall be my people.

Wherefore come out from among them, and be ye separate.

We call them pilgrims. But they did not call themselves that. They called themselves Separatists.

“Work out your salvation with fear and trembling,” says the apostle. Would you like to know a little bit about my fear and trembling? How about a nightmare? How about two?

One of the nightmares goes like this: I am holding a baby boy in my arms, and I am full of dread. The baby boy isn’t one of mine. Maybe he is supposed to represent all four of them. Maybe he is supposed to represent something else. Maybe boyhood per se. Maybe my nightmares do not have to make that much sense. My middle name is Daniel, but I am no interpreter of dreams and probably wouldn’t be good at that even if my middle name were Sigmund. (Freud, just one vowel off from fraud—now, there is some psychoanalytic chum for you.) As I hold that baby boy, I pull him very close and hold him very tight, and I know, somehow, that he is about to disappear, fading into nothingness. Soon, he vanishes like steam, and I am full of grief. Maybe he is supposed to be a ghost or a hallucination. I do not know. I can tell you that it gets me up at 2:27 a.m. on a Wednesday to go stand outside my boys’ bedrooms and debate whether to risk waking them up by going in to check on them. Another nightmare goes like this: I am in a rundown house, and I can hear one or more of my sons crying in another room. But, as I go from room to room, I cannot find my sons. They are always on the other side of some wall or door, always crying, and, when I follow the sound of their distress, they are not there. I have an idea that eternity in this run-down house is what Hell would be for me.

(Have some turkey. We’ll have pie later, too.)

You get new things that make you thankful, and, at the same time, you get new things that make you afraid. It is a package deal, sides of a coin. One of the interesting sensations attending fatherhood is that moment when you can almost physically feel the locus of your fear moving out of your own body into a tiny one you are just seeing for the first time. You experience an entirely new kind of terror.

In a moving (and, unhappily, premonitory) passage about suicide, the novelist David Foster Wallace considers the case of people who jump from burning buildings.

Make no mistake about people who leap from burning windows. Their terror of falling from a great height is still just as great as it would be for you or me standing speculatively at the same window just checking out the view; i.e. the fear of falling remains a constant. The variable here is the other terror, the fire’s flames: when the flames get close enough, falling to death becomes the slightly less terrible of two terrors. It’s not desiring the fall; it’s terror of the flames. And yet nobody down on the sidewalk, looking up and yelling ‘Don’t!’ and ‘Hang on!’, can understand the jump. Not really. You’d have to have personally been trapped and felt flames to really understand a terror way beyond falling.

A terror way beyond falling. My fear of death has not diminished in middle age—it has been multiplied by five. I do not want to die any time soon and miss out on this “brave world, and richly furnished,” that God in His infinite goodness has seen fit to provide for such a specimen as me. But when I think about the possibility of an early death, the part that is almost unbearably excruciating is thinking of my wife and sons grieving, of their being deprived of the man who is, whatever his considerable and well-documented inadequacies, the only husband and father they have. My terror of death is “still just as great as it would be for you or me” considering the eventuality on any ordinary day. The fear of death “remains a constant. The variable here is the other terror.”

Be careful which virtues you pray for—God may give you what you are asking for, and, if Scripture is any guide, you are not going to enjoy that very much. As you may have noticed (and as a few of you have remarked), God has given me many, many different means and opportunities to learn the virtue of humility, to only very modest effect. I do not mind it so much. But what terrifies me the most is that He may decide that I need a lesson in gratitude. And I know how He goes about teaching that lesson.

A decade ago, I might have said, and may even have been genuinely convinced, that I was perfectly happy living my life as a man largely unattached to the world, a man with very little to lose beyond his own petty comfort and satisfactions and not much of real value beyond the love of a few good friends. If I had gone out in a blaze of indifference on a speeding motorcycle at 3 a.m. while thinking about Hunter S. Thompson’s meditation on late-night rides …

So it was always at night, like a werewolf, that I would take the thing out for an honest run down the coast. … The dunes are flatter here, and on windy days sand blows across the highway, piling up in thick drifts as deadly as any oil-slick … instant loss of control, a crashing, cartwheeling slide and maybe one of those two-inch notices in the paper the next day: “An unidentified motorcyclist was killed last night when he failed to negotiate a turn on Highway I.”

I had plenty of chances to, and it was good enough for a Meat Loaf song, wasn’t it? It beats suffocating inside a giant can of pork and beans.

But, now—no motorcycle, no more werewolf rides down the coast or out in the desert or out near there somewhere in Spain with the Castejón Mountains in the background. I used to go “AmEx camping,” just get in the car or on the bike with a couple of changes of socks and underwear and the trusty American Express card and go. It didn’t matter where, because it didn’t matter where.

Now, it matters. Every trip to the Kroger matters. To have something truly precious to lose is a great blessing—and a great terror.

We usually celebrate Thanksgiving with my wife’s family in Massachusetts. I am happy about that. I enjoy spending time with my in-laws: They are excellent cooks with a great fireplace, Massachusetts is a natural Thanksgiving setting, and I remain the undefeated Trivial Pursuit champion of the extended family, including one game where I took on the entire family singlehandedly. (Being the precise age I am gives me an unfair advantage when it comes to the original edition.) I do my best to keep what Winston Churchill called the “black dog” at bay. But I hear him sniffing around the door like Warren Zevon’s werewolf.

There are no more Williamsons left to celebrate holidays with, and the unhappy if squalid and tedious little truth is that holidays with my family were not the sort of thing that brought on great powerful feelings of gratitude. I can remember a Thanksgiving when my mother complained that her daughter-in-law was not helping in the kitchen and then breaking down into an unhinged, screaming rage when the daughter-in-law tried to help. I do not believe my mother was ever able to spend another holiday with her granddaughter.

But the one I remember most vividly was a Christmas morning with the man who would become my mother’s second husband, a troubled, alcoholic Vietnam veteran who was living with us at the time and who had not gotten her a gift for Christmas. He improvised and proposed marriage to her instead, though without the benefit of a ring. I believe I was 6, and even I understood what was happening, and that this would end badly, either by his reneging on the engagement or, the worse option, going through with it. He used to keep careful track of how many beers he drank and stack his Silver Bullets in a neat pyramid as he finished them off and then drink mouthwash or Mexican vanilla when he ran out of proper booze, and he once beat me badly enough that I was disoriented for some time afterward, though I cannot remember how long. It was an unhappy marriage and a short one, though not short enough to my thinking, then and now.

Holidays were sometimes disappointing and sometimes agony. I worry sometimes that I will go Clark Griswold and make my family miserable by trying to make holidays so perfect that they are ruined. So far, I have avoided Griswoldism by means of sloth—those Christmas lights around my mailbox were up very, very late until a week or two ago, but now they are up early. Soon, they will be perfectly timely. Some things do take care of themselves in time.

Well-meaning friends sometimes try to tell me that my family stuff was, looked at properly, all for the best, that these experiences built character and made me resilient, that these made me the man I am, which they mean in a complimentary way without knowing how it sounds on the other side of these particular slightly protruding ears. Freddy Nietzsche’s proverb notwithstanding, that stuff did not kill me, but it did not make me stronger, either. It can make it hard to enjoy the holidays without a little shadow of regret, which is something that I do not want to share with my family. There are some things that just do not get better, some injuries that get worse over time rather than healing, some kinds of loneliness that just become a part of who you are, however many friends you have, however joyful a family with which you are blessed later in life. It doesn’t stop. There is no upside to any of that, and nothing in it for which to be grateful. But it is personal and, if it is not your private affair, it is tedious to hear about. So I do not usually say what I am thinking when any of that stuff comes up, as it does from time to time, especially with my oldest friends, who, being Americans, are addicted to the power of positive thinking, even for horrors, applying their positivity thick like a heavy coat of revisionist varnish.

Nothing good was going to come of it. But, luckily for me, I knew from a young age what I had to do:

“Wherefore come out from among them, and be ye separate.”

I went on a pilgrimage once. Of a sort. It was in Rome and was organized by some American Catholics very connected to political circles at home and at the Vatican, which meant first-rate guided tours and a lot of two-pasta-course lunches with cardinals—the kind of pilgrimage where you gain three pounds. Beyond forgoing a nice hotel room, there was not much in the way of mortification of the flesh. I may have provided some opportunity for mortification to the other pilgrims—I don’t think I was very good company at the time and may even have been on the verge of unsufferable. “You never know just how you look through other people’s eyes,” and that probably is a mercy. I did sleep in a little dormitory bed that might have made me feel like a college student if I had ever lived in a dorm, which I hadn’t. What I felt like was a very comfortable monk. But, of course, a monk for a day or a week is no kind of monk at all, just as a marriage without vows is no marriage at all.

Thomas Merton, the Trappist monk and writer, rejected the notion that life in the monastery amounted to a retreat from the world and insisted, instead, that the life of the monastery, with its prayer and contemplation, is at the very center of the world, that the prayerful monk takes a “true part in all the struggles and sufferings of the world.” Or, as his admirer Father Henri Nouwen put it, “When I pray for the world, I become the world; when I pray for the endless needs of the millions, my soul expands and wants to embrace them all and bring them into the presence of God. But in the midst of that experience I realize that compassion is not mine but God’s gift to me. I cannot embrace the world, but God can. I cannot pray, but God can pray in me. When God became as we are, that is, when God allowed all of us to enter into his intimate life, it became possible for us to share in his infinite compassion. … True contemplatives, then, are not the ones who withdrew from the world to save their own soul, but the ones who enter into the center of the world and pray to God from there.”

Manhattan has the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, while Father Richard John Neuhaus affectionately called his relatively poor and architecturally modest church in Brooklyn (which he served in his days as a Lutheran minister) “St. John the Mundane.” Is one of those the center of the world that Nouwen wrote about?

We used to say of my hometown of Lubbock, Texas: “It isn’t the middle of nowhere, but you can see it from there.” But it is the middle of somewhere.

The center of the world is in the monastery, in the cathedral, in the tabernacle, at the corner of 73rd and Park Avenue, high on the Llano Estacado, high in the Himalayas or here in these mountains, cold today and lightly sugared with snow—the center of the world is where we find it. The cathedral is where we find it—where we build it, and so is the tabernacle. That mystical center is the place we pilgrims are going, wherever that happens to be, because we bring it with us only to find that it was already there. It is “the cross that raiseth me.” It is the cross we carry, and the pilgrim ship that carries us across the dark waters, it is the shore we land on, and all of us pilgrims are standing on holy ground because holy ground is the only ground there is to stand on, sanctified and consecrated by the touch of its Creator at the moment of its creation. And who or what could deprive creation of its holiness? “God saw every thing that he had made, and, behold, it was very good.” Gratitude is, in a sense, the spiritual discipline of trying to align ourselves with God’s own stated point of view on the matter. But we are small and vulnerable, easily wounded, often resentful, and—the point, as I experience it, keeps getting sharper—not made for this world. To try to take up God’s point of view is not an easy thing. Bitterness is easy. Indifference takes more work, but I have never shied away from labors of that kind.

It is 2:27 a.m. I have shaken off the bad dreams. I am awake, all the way awake. The triplets still sleep in our dining room—it will be a few more months (and a bathroom renovation) before we move them upstairs. Our older boy sleeps soundly in his little room, having recently transitioned to his first big-boy bed. I think I have managed to avoid waking my wife. If our dachshund, Pancake, is awake, she is content. God’s creatures. Well done, Lord. I try to “enter into the center of the world and pray to God from there.” The prayer of a righteous man availeth much, Scripture says, but, for now, the world will have to make do with mine—the righteous are still in bed. They don’t have my dreams. There is a little snow blowing around outside, and just enough moonlight to see the babies, bellies down, breathing nearly in unison. There will be deer-hoof prints in the snow in the morning, possibly bear tracks. It is cold. But we are warm here in our little pilgrim ship, and, as far as I can tell at the moment, our course is true, with fair winds and following seas. And I think I know, at least for the little piece of time between 2:27 a.m. and 2:29 a.m., what is required of me.

I look upon His works and, behold, they are very good.