“When we assumed the soldier, we did not lay aside the citizen,” Gen. George Washington avowed to the New York Provincial Congress in 1775, “and we shall most sincerely rejoice with you in that happy hour, when the establishment of American Liberty on the most firm and solid foundations shall enable us to return to our private stations in the bosom of a free, peaceful, and happy country.”

Washington, the beau idéal of martial republicanism and an exemplar for generations of American posterity, set the tone for the expectations of personal sacrifice in the cause of liberty, and represented through personal example the duality of military service as an essential component of republican citizenship. Citizens of a republic could claim and affirm their place in civil society through acts of service. But for Washington, and presumably for the rest of his generation, such service (in this case, service in the military), represented a “fatal, but necessary operation of war” whose temporariness and voluntariness did nothing to diminish the fundamental sacrifice at its heart.

Washington’s own experience as commander in chief of the Continental Army both modeled and reflected that very relationship. Though a martial figure who pursued military accomplishment for much of his adult life, Washington’s own career in the army culminated in the self-termination of his authority at the height of his prestige and power. Washington’s famous resignation, immortalized by the artist John Trumbull in his 1824 painting General George Washington Resigning His Commission, reminds visitors to the Capitol rotunda of the personal and public sacrifice expected of the warrior-servants of the republic.

Washington, like his contemporaries, was immersed in the ideals of the republican tradition, and both knew and revered the tale of Roman consul Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus, the ideal citizen-soldier for that generation. When Rome faced the threat of invasion, the patrician Cincinnatus was banished from his esteemed public position and consigned to the simple life of a farmer, all unjustly. But when Rome faced another crisis and his fellow citizens begged him for help, Cincinnatus left behind the plow and led his nation’s armies to victory as dictator. The calamity averted, Cincinnatus voluntarily surrendered his immense power, selflessly embodying the highest examples of virtue and sacrifice for the good of his fellows.

That model of disinterested selflessness formed the heart of how Washington and his contemporaries conceived of republican citizenship during the War for Independence and in the years that followed. “When a few mighty matters are accomplished here,” John Adams wrote in 1776, “I retreat like Cincinnatus, to the Plough …, and farewell Politicks.”

“We have seen sons of Cincinnatus,” likewise proclaimed the former firebrand revolutionary Patrick Henry in 1788. Henry emphasized not only Cincinnatus’ military service, but also his selflessness and submission to the rule of laws inherent in the temporary nature of such service. “We have seen such men throw prostrate their arms at your feet. They did not call for those emoluments which ambition presents to some imaginations. The soldiers, who were able to command every thing, instead of trampling on those laws which they were instituted to defend, most strictly obeyed them.”

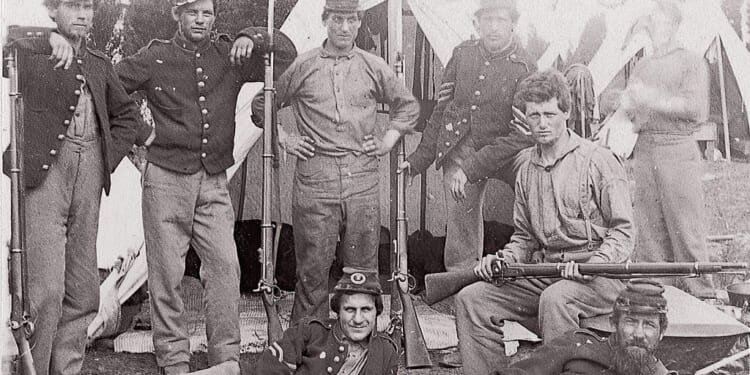

By the eve of the Civil War, Northerners and Southerners alike proudly boasted of such revolutionary traditions as voluntary service, self-government, and representative democracy. Though it seems perhaps strange to the modern ear, Civil War-era white men were, under the republican tradition, equal under the eyes of the law, a condition that Europeans could not likewise claim on such a universal scale. Their egalitarianism was not our egalitarianism, but relative egalitarianism it was. Americans in the Republic, at least those defined as citizens and members of the body politic, could claim the right to be treated the same as any other citizen by their government. Even more potent, that very government was subject to the wishes and desires of the governed.

Despite bitter divisions over slavery, the idea of union and the sense of necessary sacrifice for the republic and nation burned brightly in Civil War Americans of all persuasions, North and South. Their understanding of this responsibility sprang from their shared story of the Revolution and its costs, and yet they could, and did, sharply disagree on its proper interpretation and application. Though they faced the most destructive and divisive war in American history, with enmities that endure even to this day, Northerners of that era knew both the tremendous stakes of the fight at hand, and the price of surrender—or worse, of betrayal of the great principle of republican government.

Though they fought bitterly over the legacy of the Revolution and of the very meaning of republicanism, Civil War Americans agreed that their liberty demanded a willingness to engage in sacrifice, both for the good of the nation as they defined it, and for the survival of individual freedoms.

As the Philadelphia Public Ledger put it on June 7, 1861: “[W]e are fighting for … [a] great fundamental principle of republican Government—the right of the majority to rule. When the ballot-box was substituted for revolution, it was thought that all violent changes in established governments, all sudden overthrowing of political structures, would be obviated, for the will of the people could be peacefully known through the ballot.” Secession and rebellion, therefore, represented a rejection of lawful elections, a denial of the fundamental principles of self-government and political equality under the law, and a rejection of the sacrifices of previous generations, including that of the Revolution. “We are fighting to prove to the world, that the free Democratic spirit which established the government is equal to its protection and its maintenance. If this is not worth fighting for, then our revolt against England was a crime, and our republican Government a fraud.”

Antebellum Southerners drew from the same Revolutionary well as their Northern countrymen. Yet when the winds of secession blew through the winter of 1860-1861, cracks in the common edifice began to appear. White Southerners, particularly those who owned slaves or supported the system of slavery, rooted much of their understanding of the Revolution in values like independence and freedom from interference; in the peculiarly outward-facing idea of personal honor; in the deep roots of place, tradition, and community; in the necessity and value of social hierarchy and Christian virtue; and in the preservation of the institution of slavery and the racial order upon which it depended.

Southerners emphasized personal sacrifice for the collective right of constitutional self-government, and proudly traced their lineage to Southern sons of the revolutionary generation. As the Atlanta Southern Confederacy declared in 1861: “We [the South] quit the Union only because we had to quit those who had quit the Constitution. We chose to adhere to the substance, and leave the form. … We have resolved to preserve and [Lincoln] to destroy self-government. If you are conquered, you are no more freemen, but slaves. If you conquer, you remain free. Confiscation and chains, is the openly declared policy of our enemies.”

Though they fought bitterly over the legacy of the Revolution and of the very meaning of republicanism, Civil War Americans agreed that their liberty demanded a willingness to engage in sacrifice, both for the good of the nation as they defined it, and for the survival of individual freedoms.

As the nation reeled, and then slowly recovered, from the Civil War, new challenges and new tests for the notions of republicanism and sacrifice remained. Two world wars and the ordeals of the Cold War and the global war on terror led Americans to reimagine the role of sacrifice, particularly that of military service, in the nature of republicanism. What some have come to call the “civil-military divide” emerged, as the cultural, social, and political gap between the U.S. military and the civilian population it serves has replaced more universal notions of service and sacrifice. The American military remains among our most respected institutions, and yet it is increasingly separate from the broader public in ways that would have been foreign to Americans of the 18th and even 19th centuries.

The national revolutionary heritage that had been won by force of arms, paid for in toil and blood, demanded purposeful dedication and a willing buy-in from each subsequent generation, in military service, in public service, or in selfless dedication to the ideals that inspired, and continue to inspire, the American experiment. A 2018 Rand Corporation study revealed that a “call to serve” was the primary institutional motivation for modern American soldiers, and that spirit of sacrifice and service remains strong among our military. Whether that same motivation still survives among the American people as a whole is a more difficult question to answer.

Since the end of the draft in 1973 and the tribulation of the Vietnam War, the United States has relied on a voluntary military, which means only a small percentage of Americans serve or have close ties to someone who serves. Military service tends to be more common in specific regions (the Southern states and California), creating geographic imbalances in military representation, and most major military installations are located in only a handful of states, or overseas. Modern military service is often a family affair; children of service members are significantly more likely to join than those from civilian families. The military emphasizes hierarchy, discipline, duty, and cohesion—values that can differ from civilian norms of individualism and personal freedom, that many Americans are unwilling to surrender. Civilians may romanticize or misunderstand military life, while service members may feel civilians are disconnected, naive, or unappreciative of their sacrifices. And, the very notion of sacrifice, so essential to earlier national understandings of the meaning and nature of republicanism, feels increasingly abstract or even meaningless to some.

Since 1776, republicanism and the ideals of the American Revolution have weathered great tests, and perhaps in no clearer instance than the Civil War. Civic virtue in the form of military service maintained a claim of sacrifice for the freedoms and privileges of a free citizenry ever since. To be clear: This sacrifice is not sacrifice in service to the state, nor certainly to any one person or political tribe, nor must it be exclusively, or even mainly, military in nature. It is rather a willingness to gladly set aside one’s personal or private interests in the defense of the ideas, and ideals, that animate our national polity. Put another way, republicanism requires a collective dedication to the well-being of our neighbor, our community, and ultimately, our national family.

As James Madison so beautifully explained, a society that substitutes “the motive of private interest in place of public duty” leads inevitably to corruption. Conversely, a government rooted in the “understanding and interest of the society” produces a “government for which philosophy has been searching, and humanity been sighing, from the most remote ages.”

Two and half centuries on, our past selves, and the freedoms for which they gave so much, continue to assert a claim on us. If Madison is right, then the destiny of the republic may depend on recovering that notion of sacrifice for the common good.