This week’s major outage of Amazon Web Services’ cloud operation once again highlights the vulnerability of the world’s commercial, government, and social interactions due to a reliance on a handful of providers. The outage—which took several hours to resolve—impacted applications across a wide spectrum: social media, gaming, food delivery, streaming, financial and health services, and transport, among others. The effects were felt internationally—including in New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and India—and it was reported to have caused mayhem amidst the country’s Diwali celebration.

The core issue is a growing reliance upon highly networked infrastructure in the data transmission supply chain. This system is so complicated both technologically and contractually, that it has become nearly impossible for any single stakeholder to assume responsibility for managing the relationships in a way where meaningful service levels can be promised or accepted. The system relies upon a combination of best efforts. When one link in the chain breaks and the whole system is rendered inoperative, the associated costs lie where they fall on individual network participants. Even when it is possible to identify culpability for any outage, there is no reliable way for those harmed to either drive home responsibility or seek compensation for losses incurred.

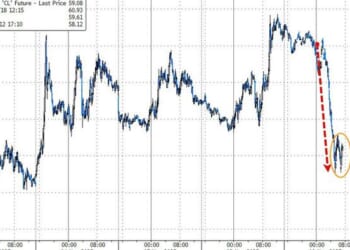

A failed Diwali technical display, a missed Zoom call, or an incomplete Robinhood share transaction at an optimal time may seem comparatively trivial. However, when aggregated globally, they constitute a significant economic and social impact. Furthermore, the frequency of such outages appears to be increasing as their scope also expands. The Amazon outage follows Microsoft’s July 2024 CrowdStrike outage, and follows other high-profile outages at telecommunications operators such as Canada’s Rogers in July 2022 and Australia’s Optus in November 2023 and September 2025. As more of society’s commercial, government and social interactions are digitized and designed or converted to cloud-based applications and platforms, the degree of vulnerability increases.

Growing cloud-based vulnerability appears to be replicating a pre-internet scenario where reliance upon technologies controlled by a small number of telecommunications firms could hold national economies and societies at ransom. The resolution then was twofold: High-value commercial customers could contract the firms to comply with minimum service levels or face the consequences in court; residential consumers could rely upon government monitored and enforced regulations to achieve similar outcomes. Following the AWS outage, similar calls have been made regarding the cloud platforms. As a small number of them (three or four internationally) hold so much power, can they not be subject to similar regulations or service-level guarantee provisions?

While conceptually attractive, it is difficult to see how such controls could be practically and meaningfully implemented in a cloud-based world.

First, contractual connections in a much simpler telecommunications world directly linked the end consumer with the responsible service provider. A direct line of accountability flowed linearly from consumer to provider—if a call originating in New Zealand could not be connected to a subscriber in the United Kingdom, the UK provider was contractually bound to the NZ provider and thereby the NZ consumer. In a networked environment, however, there is no direct contractual linkage. The benefit that the internet brought—resilience by breaking the requirement that data flows along contractual channels only, and the best efforts obligations that this necessitated—effectively renders a contractual solution impossible. While a Zoom customer might theoretically be able to hold Zoom contractually responsible for delivering a defined level of service, it cannot hold AWS—or any other cloud provider Zoom uses—accountable because it has no direct relationship. Moreover, neither Zoom nor AWS are likely to be willing to enter into a service level agreement of this type because neither can contractually constrain other providers in the supply chain, who influence service-level performance – such as the consumer’s ISP.

Second, regulatory controls are problematic because this is an international issue. While one country may implement regulatory controls, others may not. Alternatively, the controls may vary between countries, encouraging cloud operations to shift to the locations most advantageous to them. Each jurisdiction must be willing to exert monitoring and control effort within their boundaries, the benefits of which could mostly accrue in other jurisdictions. The efforts exerted are unlikely to be globally optimal. It may be possible to obtain some form of global cooperation to standardize regulatory approaches—for example, via the newly-established United Nations Global Dialogue on AI Governance—but such processes are not conducive to rapid responses in fast-moving environments.

Although reaching satisfactory resolutions may be problematic, a multi-stakeholder conversation must begin now on how—for society’s good—cloud-based systems can be made more resilient.

The post We Need to Talk About Cloud Resilience appeared first on American Enterprise Institute – AEI.