The comedian John Mulaney tells a funny—and terrible—story about trying to cure himself of his cocaine addiction by instructing his financial manager to keep cash out of his hands. No cash, no coke—I guess his dealer didn’t take Venmo. What happened next was a predictable series of shenanigans in which the comedian thought up ways to, in effect, embezzle from himself, e.g., buying a $12,000 watch and selling it for $6,000 on the same day. Mulaney’s story of desperate addiction offers a good example of one of the common mistakes we make in our current econo-political debate: trying to use economic means to solve non-economic problems. Mulaney’s problem was not economic: He has been very, very successful and probably could blow $6,000 a day for a very long time without endangering the mortgage payment. His problem was that he loved cocaine.

There are a great many modern pathologies and problems that often are described as results of capitalism or as aspects of capitalism—of “late capitalism,” as the pseudointellectuals sometimes put it. For example, as formerly poor and hungry countries have become more prosperous and better-fed, they have seen an increase in obesity and diabetes, and, in some cases, they have seen higher levels of alcohol and tobacco use as increased private incomes enable the consumption of what had been unobtainable luxuries. Use of some other drugs has increased, in some places, with wealth: You need a little bit of money to have John Mulaney’s former bad habits. There are increased environmental pressures and externalities associated with increasing wealth, too, as the newly affluent consume more energy, food, and petroleum products (plastics, chemicals, pharmaceuticals—the list is long) than they had. When poor people leave farming villages for higher-paying jobs in urban environments, there are new pressures put on everything from utilities to transportation networks to housing.

Capitalism becomes a go-to bogeyman, the witch behind every contemporary malady: “Blame capitalism for men’s loneliness,” etc.

There surely are some social evils that are the work of capitalists—as Willi Schlamm famously put it, the problem with capitalism is capitalists (but the problem with socialism is socialism). But greed, dishonesty, and short-sightedness are human qualities present in men and women under every economic arrangement. Socialists steal, lie, and exploit, too.

In the same way, nearly all of the problems attributed to capitalism are (or were) present in much more intense forms in non-capitalist economies than in capitalist economies: See, for example, the environmental record of Communist China or the results of forced industrialization in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. Nutrition and health outcomes are not great in North Korea or Venezuela. Municipal services in Cuba are … also not great.

It is not that the medical or environmental or cultural problems of the rich capitalist world are not real or that they are unimportant—it is that these are problems that are mainly non-economic in origin and unlikely to be much improved by economic means. And where economic means are employed, they often are simply a stalking horse for old-fashioned state coercion, as in Barack Obama’s promise to “bankrupt” coal-based businesses—a prohibition disguised as a fine or a tax is still a prohibition. People who propose putting a $1,000 tax on a box of ammunition are not actually engaged in tax policy. They are like John Mulaney trying to treat a psychiatric problem through cash flow management.

But what about all that economic inequality we hear about? Surely that is a problem that is economic in origin? That is, at most, half right: economic—yes; a problem—no, not really.

An extraordinary thing has happened with the incomes and total wealth of the tippy-top of the distribution since the 1990s and the emergence of the internet and that vaguely defined collection of international phenomena we call, for lack of a better word, globalization. The fortunes acquired by such tech titans as Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk are indeed remarkable. They have almost nothing to do with the economic situation of the poor or the middle class, and they are not, in the main, the result of public policy. That is not to say that public policy could not diminish those fortunes (for instance, by simply seizing them, as many of my leftist friends desire), but Amazon and Apple and such have not exploded in value the way they have mainly because of government favoritism or political steering, though, the world being a fallen place, these exist and are factors. (Critics here will point to the subsidies enjoyed by Musk’s constellation of rent-collecting enterprises, and they are not wrong to do so. But even with these subsidies in mind, the broader point stands, for reasons that I hope the following lines will make clear.) What has made Bezos’ splendid fortune is the growth and integration of markets: If you have the most successful car dealership in Plainview, Texas, then you probably do pretty well—but you do a lot better if you have the most successful car dealership in Los Angeles. Same business, bigger market, hence, bigger returns to small improvements in margins.

The poor are not poor because the rich are rich. The poor are less poor because of the same economic factors that have made some of our rich guys so shockingly rich.

If Jeff Bezos were the most successful shopkeeper in New York City, he’d be wealthier than if he were the most successful shopkeeper in Little Rock or Indiana—as it happens, he is the most successful shopkeeper in the world, serving hundreds of millions of users in more than 100 countries. Where markets are very large, returns to profitable innovation, efficiency, investment margins, excellence in corporate management—or luck!—also are very large. When Saks & Company was just a shop on Fifth Avenue, there was no way for its owners to make the kind of profits that a large, international chain of department stores could—to say nothing of the kind of profits Amazon can generate. But these profits are not, vulgar class-war rhetoric notwithstanding, deductions from the common good or from the share of wealth available for distribution—they are the result of wealth created, not merely wealth distributed.

The poor are not poor because the rich are rich. The poor are less poor because of the same economic factors that have made some of our rich guys so shockingly rich. Creating wealth makes societies—and the world—wealthier. Even with the returns going lopsidedly to a relatively small number of investors, wealth creation of the kind that makes billionaires also produces tons of economic benefits and secondary activity, tax revenue, etc. The thing about richer societies is, they’re richer.

But, strangely, when my progressive friends talk about economic inequality, they invariably talk about the incomes of the very wealthy—and almost never about the poor. And there is a reason for that: The story of the economic situation of the world’s poor does not offer very much rhetorical fodder for the enterprising anticapitalist.

Most of the world’s population lived in extreme poverty in 1800—about 80 percent of the human race. By 1980, that share was down to about 43 percent—a substantial improvement. By 2015, that number was down to around 9 percent, and today it is a little less than that. (NB: Estimates vary among sources, of course, but every credible account has the share of the world population living in extreme poverty radically reduced, by about the same proportion in the same years.) By historical standards, very few people live in extreme poverty today, and they are concentrated in sub-Saharan Africa, which accounts for about two-thirds of the population living in extreme poverty.

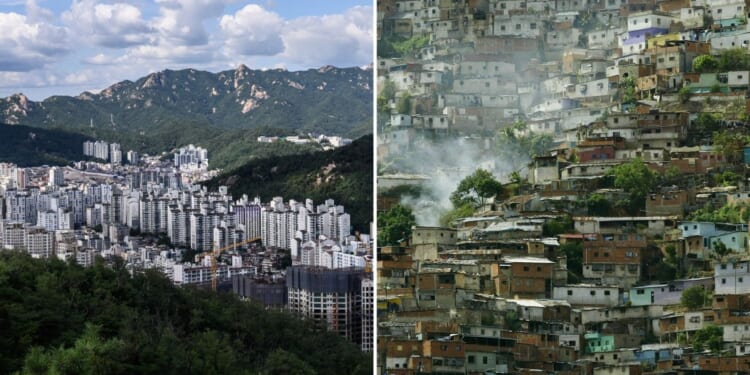

A little capitalism goes a long way. When the government of Narasimha Rao began its program of economic reform in India, the average citizen of that republic died before age 60; today, the typical Indian lives past 70. Left-wing anticapitalism is not the only kind of anticapitalism, and right-wing anticapitalism has predictable results: In 1960, South Korea was under a military dictatorship with its boot heel on a very regimented economy, and the average life expectancy was 53.8 years; a steady program of liberalization saw South Korean life expectancy grow from about 63 years in the 1970s to 73 years in the 1990s to more than 83 years today. North Korea, on the other hand, saw its average life expectancy decline by a decade in the 1990s.

From the United States to the United Kingdom to Europe to India to South Korea, the story is the same: Capitalism is good for people, and it is very good for the poorest people. The reasons for that are obvious enough: Relatively poor societies do not have very much to share with the neediest among them, nor do they have the kind of resources that allow adequate investment in big infrastructure projects that improve sanitation and access to clean water, which are key to improving public health and life expectancy. Often, these are a matter of public works rather than a matter of market goods provided by for-profit entities. The thing to understand is not the libertarian cliché that “free markets will take care of it,” maybe with an assist from private charity, which is often true but not always.

Rather, the thing to understand is something that even Karl Marx appreciated: Capitalism produces the level of economic development and wealth that is necessary in order for a society to have adequate resources to direct at such age-old problems as profound poverty, preventable diseases, or the provision of public goods. Marx thought that the wealth of capitalism would provide the fertile ground into which to plant the seed of socialism, but he was not quite right: Socialism, for reasons having more to do with the use of knowledge in society than with industrial production techniques or financial incentives, always and everywhere fails on its own terms. What has instead grown out of the rich soil of capitalism is … more capitalism, more complex capitalism, more global capitalism, more productive capitalism, together with a variety of approaches to the design and implementation of social welfare programs, which liberal-democratic countries (and some less than liberal and not quite democratic) have adapted to their own local conditions with varying degrees of success: Even within the richest nations of Europe, there are radically different models of social welfare (e.g., Sweden vs. Switzerland), while peoples rooted in different cultures have come up with reasonably effective—sometimes extraordinarily effective—alternatives of their own, as in Singapore and South Korea. But what Sweden and Switzerland and Singapore and South Korea have in common is capitalism. What North Korea and Venezuela and South Sudan have in common is the absence of capitalism. North Korea and Venezuela offer two distinct flavors of socialist backwater, while in South Sudan the state-run oil enterprise is something close to the entire economy.

Capitalism is one part of the magic formula—it goes along with liberalism and democracy, and, just as there are different versions of capitalism appropriate to different cultures, there are different versions of liberalism and democracy. Swiss democracy is not very much like American democracy, and American liberalism is not precisely the same as the liberalism of Germany or that of Singapore. The rich world is not an Erector set with standardized parts. It is more like a cake recipe with ingredients that may vary in both their composition and their relative proportions, according to taste: democracy, political accountability, the rule of law, independent courts, a free press, etc. The capitalism bit of that comprises property rights, freedom of exchange, freedom of contract, trade, a stable money supply, etc. These things together have produced remarkable results in everything from poverty to education to food production to health to occupational safety to peace to every other factor my friends over at Human Progress track.

Even in regimented and autocratic systems such as that of China, it is the zones of relative liberalism that have produced the wealth that has relieved extraordinary poverty.

In 1800, most of the world was desperately poor. In 1980, nearly half the world was desperately poor. Today, something like 9 percent of the world is desperately poor—and what most of that 9 percent most desperately needs is access to capitalism, to its tools and opportunities. That progress did not happen by accident, and it was not the result of some committee of experts thinking deep thoughts in Washington or Brussels or Davos. (Much less Beijing or Moscow.) And while I am sympathetic to a lot of that all-the-way libertarian stuff, you don’t have to pretend that this is some kind of anarcho-capitalist fairy tale in which government plays no role, inasmuch as conventional modern capitalism expects—and counts on—government to play some role: Property has to be protected, contract disputes have to be litigated, public goods need to be provided. Sometimes private actors and market-based players can get a lot of that done, and that’s great. But, in the modern, developed-world experience, capitalism works best with competent government based on liberal democratic traditions.

There is nothing more nonsensical than hearing some ingrate—Bernie Sanders, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, J.D. Vance, Sohrab Ahmari—insist that we need to reimagine capitalism or revamp it or remake it from the inside out. Capitalism works just fine—let that golden goose be. What we should be talking about is much more in-the-weeds and much less grand: What kinds of real-world reforms are needed in our tax system and public finances? What should we do about the persistent lack of price transparency in health care? Why do we get such poor results from our public schools even as we spend more and more money on education? How should we go about preventing financial disaster in the public pension systems? How do we honor democratic norms and local political accountability while getting rid of the political sclerosis that has arrested so much infrastructure development and housing construction? Those are real questions. None of them requires “reinventing capitalism” or whatever dumb catchphrase the politicians are using this year.

Capitalism—the thing that happens when property rights are protected and the freedom to exchange is honored—not only has a record of raising people out of poverty, it is the only economic system with a record of doing so. Even in regimented and autocratic systems such as that of China, it is the zones of relative liberalism that have produced the wealth that has relieved extraordinary poverty. That China remains an autocratic police state is not an indictment of capitalism—it is another example of the fact that economic policies solve economic problems but generally are not much good for non-economic problems. John Mulaney could not cure his cocaine addiction by managing his money—though surely it is the case that his considerable wealth provided him with resources to support his efforts at cleaning up his life when he worked up the will to do so. That approximates the role of capitalism in a complex society: Capitalism does not cause or cure diabetes or obesity or environmental degradation or urban dysfunction—but it does provide us with resources that give us the ability to make better choices, once we have worked up the will, under conditions that are much more favorable than those we would endure if we had a Cuban economy or a Venezuelan economy or a North Korean economy. The proverb attributed to Deng Xiaoping is true but not the whole truth: “It is glorious to get rich.”

If you doubt that, ask someone who used to be poor.