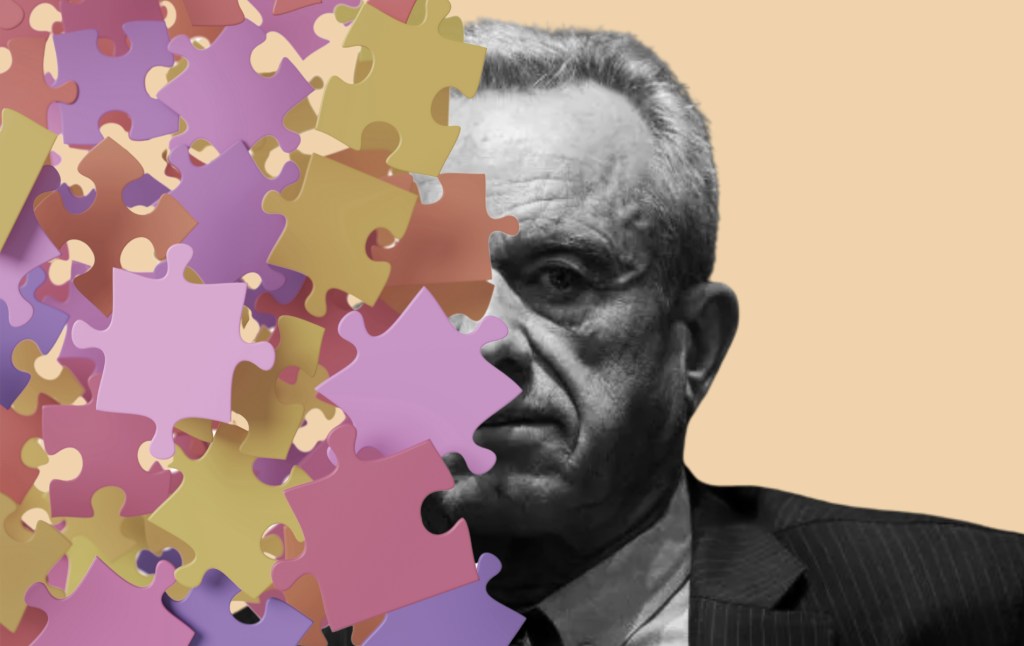

President Donald Trump hailed Robert F. Kennedy Jr. as a reformer when appointing him health and human services (HHS) secretary, declaring Kennedy would get “the American people the facts and the answers that we deserve.” Including about autism.

Since taking office, Kennedy has made the study of autism and its causes a focal point of what he hopes to accomplish at HHS, announcing the launch of a study examining the disorder’s causes and expounding on what he calls an “alarming rate” of diagnoses. But many of his statements about autism conflict with established, mainstream scientific understanding. Diverse coalitions of autism scientists and advocates have mobilized to counter Kennedy’s assertions, noting his positions ignore decades of peer-reviewed research.

Here’s how Kennedy’s recent claims stack up with the latest scientific understanding of autism.

On an autism ‘epidemic.’

In an April 2025 press conference on autism rates in the U.S., Kennedy referred to an “autism epidemic,” calling the latest prevalence numbers “shocking” and “relentless.”

Autism, officially called autism spectrum disorder (ASD), is a condition that affects how the brain develops and works. Someone is diagnosed with autism when differences in the way they communicate, their range of interests, and their behavior create difficulties in their daily life, according to the diagnostic criteria laid out in the current Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR), the American Psychiatric Association guide for mental health professionals.

Kennedy is correct that more children today are diagnosed with autism than in the past. The latest Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report, released April 15, estimates that about 1 in 31 American kids born in 2014 were diagnosed with autism by age 8, up from 1 in 36 for those born in 2012 and 1 in 44 for those born in 2010.

But experts say that these increases in recorded diagnoses should not be confused with an explosion in the real number of cases of autism. “There has been, certainly an increase in the number of children diagnosed with autism, but it’s really the result of a whole variety or bureaucratic or systematic changes and how we look at autism,” said David G. Amaral, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of California at Davis and founding researcher of the MIND Institute, which studies autism and other neurodevelopmental disorders.

Autism is a relatively new diagnostic category, introduced in the DSM-III in 1980. Since that time, the definition has broadened considerably. Autism used to be a much narrower diagnosis that excluded both individuals with more mild disability (who would have been diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome, generally characterized by having poor social skills but good verbal ones) and those with more pronounced disability (who would have been diagnosed solely with an intellectual disability but now might be diagnosed with autism with an intellectual impairment thanks to changes in clinical practices and increased awareness of the condition).

When Kennedy cites historical autism rates of 4.7 per 10,000 kids, he appears to be referencing 1975 data that predates modern diagnostic criteria by almost 50 years—when what we today call autism was considered a form of schizophrenia. Individuals who would qualify for an autism diagnosis today would not have been diagnosed as such in the 1950s and 1960s, when Kennedy grew up, simply because of how autism was defined at the time, said Amaral.

Many other changes in the cultural and health care landscape contribute to what looks like an increase in autism diagnoses. For instance, even in the recent past, a family would have had little incentive for seeking out an autism diagnosis. Until about a decade ago, many autism therapies, which can be expensive, were paid for out of pocket. But in 2014, Medicaid began covering autism services. Today, all 50 states require state-regulated health plans to cover some form of autism treatment. Having a diagnosis now unlocks access to these covered services.

When not everyone who is autistic receives a diagnosis, the official count will be lower than the actual number of cases. As access to accurate screening improves, more cases emerge accordingly.

The state-level data within the CDC report support the idea that increased access to screening helps drive increased prevalence of autism. Of the 15 states used to generate the national estimate, California reported the highest prevalence, with approximately 1 in 19 8-year-olds diagnosed with autism, while a site in Texas had the lowest at roughly 1 in 103. “I don’t believe for a moment that the numbers are that different in California and Texas,” said Amaral. The CDC report attributed California’s higher prevalence to the state’s push for early detection using the Get SET Early Model, a screening program without an equivalent in Texas.

On the severity of autism cases.

In his remarks about the new prevalence data, Kennedy claimed that “most cases now are severe” and characterized autism as a “tragedy” that “destroys families,” suggesting that autistic individuals would never “hold a job,” “go out on a date,” or “use a toilet unassisted.”

These statements swiftly drew criticism from autism experts and advocates, who called the remarks disrespectful and untrue. American Psychological Association CEO Arthur C. Evans Jr. countered: “People with autism can and do lead rich, productive lives.”

While a HHS spokesperson later walked back some of Kennedy’s remarks, stating that Kennedy was only referring to severe cases, experts say his perspective is still out of step with current scientific thinking about autism.

Autism varies widely among individuals, as does how disabling it is. A 2023 CDC report suggests that about one-quarter of cases could be classified as “profound autism,” while other research arrived at a number closer to 10 percent. No evidence supports Kennedy’s claim that most autism cases today involve severe disability, nor that the proportion of severe cases is increasing over time, noted Amaral.

Today, researchers recognize that autism’s impact on daily life can even change significantly across a person’s lifespan. For example, Amaral and his colleagues at the MIND Institute assessed autistic children’s symptoms at age 3 and again at age 11. About one-third of the study’s participants had less severe symptoms by the time they entered middle school, according to results published in 2022 in the journal Autism Research.

Early intervention can make a meaningful difference in what is possible as an autistic child grows up. For instance, therapies that involve teaching parents how to support their autistic children result in improved social and communication skills and reduce problematic behaviors, a 2022 analysis of randomized controlled trials concluded. These gains could help autistic kids develop more rewarding friendships and reduce harm from self-injury.

“The brain is incredibly plastic,” explains Amaral, “Even with an issue [like autism] that potentially makes it more difficult, the potential for real change over time is always there.”

In contrast to Kennedy’s alarming interpretation, this view suggests that the CDC’s rising prevalence statistics may actually represent good news: More children receiving accurate autism diagnoses could mean more kids accessing appropriate health care that helps them thrive.

On the possibility of an environmental cause.

Under Kennedy’s direction, HHS announced a plan to assemble a team of scientists to identify the cause of autism, pledging “to begin to have answers by September.” Kennedy, an environmental lawyer by trade, has been clear that he believes the cause is environmental.

“We know it’s an environmental exposure,” he said at the April press conference. Kennedy has framed his position as contrary to mainstream thinking: “Obviously, there are people who don’t want us to look at environmental exposure.”

But researchers have already spent decades investigating autism’s causes. “I think Kennedy doesn’t appreciate that literally thousands of researchers in the United States and around the world have been trying to figure out the causes of autism for the last 30 years,” said Amaral. These studies have examined many environmental factors, including the toxins in air, water, medicine, and food that Kennedy claims haven’t been investigated.

Some environmental exposures experienced during gestation appear to confer a small but real risk. For instance, a study in Southern California that included more than 300,000 children found that pregnant mothers who lived near the most heavily polluted local and arterial roads were about 19 percent more likely to have babies who were later diagnosed with autism compared to those living in areas with the least roadway air pollution. (Neither more moderate air pollution nor highway air pollution seemed to increase risk.) Given the latest autism rates, this would mean that roadway pollution might bump a given child’s risk of having autism from 3.2 percent to 3.8 percent.

Other research-supported potential environmental risk factors include older parents, prematurity, and prenatal toxic metal exposure. Importantly, “All of the autism causes that have been determined thus far affect the development of the fetal brain,” said Amaral.

However, none of these environmental exposures has the explanatory weight of genetics. Autism has long been observed to run in families, with data—including a study published in JAMA Psychiatry involving more than 2 million people in five countries—suggesting that autism may be up to 80 percent related to inherited genes.

With the advent of genomic research, autism scientists have been able to directly examine the genetic profiles of individuals with autism. “Twenty percent of the cases of autism are entirely linked to a genetic change,” said Amaral. While air pollution might elevate someone’s autism risk by a fraction of a percent, certain genetic mutations will result in autism virtually 100 percent of the time. So far, over 185 gene mutations associated with autism—some inherited, some occurring spontaneously during conception—have been identified.

While autism isn’t believed to have a single cause, the current scientific evidence strongly suggests that genetics is the dominant factor, with environmental influences playing a much smaller role. Despite Kennedy claiming genetics is a “dead end,” any complete explanation of autism’s cause would have to account for the substantial body of genetic evidence.

On vaccines.

Vaccines have been at the center of Kennedy’s public remarks about autism for at least 20 years. It was in 2005 that Kennedy penned a since-retracted story published jointly in Salon and Rolling Stone alleging a government cover-up involving a preservative common in the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine at that time. Kennedy has repeated claims linking vaccines and autism across the decades, including to Fox News in 2023, when he told Jesse Watters, “I do believe that autism does come from vaccines.”

Kennedy’s HHS reportedly hired vaccine skeptic David Geier to analyze data on autism and vaccines, suggesting his views remain unchanged. Kennedy’s position contradicts scientific consensus. “There is absolutely no evidence that the MMR vaccinations that take place around 12 and 20 months after birth have any link whatsoever to the cause of autism,” said Amaral. “There’s a really strong consensus in the field that autism starts prenatally.”

Since Kennedy began voicing his views, research disproving any connection between vaccines and autism has amassed. For example, in a 2019 study published in Annals of Internal Medicine, researchers reviewed medical records from all children born in Denmark between 1999 and 2010. When they compared autism rates in children who received MMR vaccination to those who were unvaccinated, researchers found that receiving the MMR shot did not increase the odds of a child being diagnosed with autism.

One reason for the persistence of the debunked vaccine-autism link is that many parents start to notice symptoms of autism in their children after they begin to receive vaccines. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends the first MMR vaccine be given between 12 and 18 months, just before it recommends screening for autism (between 18 and 24 months). As a consequence, cases of autism would naturally be uncovered after administration of the MMR vaccine based on the AAP’s schedules alone. But research suggests the timing of observing autism symptoms may only reflect when they begin to interfere with daily life, rather than indicate a new onset condition.

In fact, trained experts and brain imaging tools may be able to detect signs of autism much earlier, potentially within a baby’s first six months, according to an analysis of 25 studies. “Autistic individuals are born with autism. They don’t acquire it after birth,” said Amaral.