On June 18, the Social Security Trustees released their annual report projecting the financial status of the federal government’s largest spending program, whose 12.4 percent payroll tax is the largest tax most Americans pay, and whose benefits form the largest source of income for most retirees. The trustees, made up of the secretaries of the Departments of Treasury, Labor, and Health and Human Services along with the commissioner of the Social Security Administration, project that Social Security’s retirement trust fund will run dry in 2033, after which benefits must be cut by roughly 23 percent unless Congress allocates additional revenues. And if Congress does decide to fix Social Security entirely through tax increases—which is the logical implication of both Democrats’ and Republicans’ promises not to cut benefits—it would be the biggest peacetime tax increase in history.

But none of that is particularly newsworthy. In fact, we’ve known it for years.

Social Security was last reformed in 1983, through a combination of tax increases, benefit reductions, and an increase in the retirement age. By 1984, Social Security’s Trustees projected the program would be insolvent over the long term. By the early 1990s, the trustees projected the Social Security trust fund would run dry in the 2030s, with that projection timeframe remaining fairly constant since.

Nothing has been done to change the trajectory of Social Security’s insolvency. In fact, Congress voted on a bipartisan basis in late 2024 to make Social Security’s finances even worse, by reinstituting windfall benefit payments to certain state and local government employees.

“Two decades of governmental inaction mean that we face a larger Social Security funding problem today, with fewer and more painful options available to address it.”

But 20 years ago, for a brief moment in the spring and summer of 2005, President George W. Bush made Social Security reform the highlight of his second-term domestic agenda. I was a bit player in that effort, first heading a Social Security Administration office that specialized in computer modeling of Social Security benefit changes; then traveling the country doing town hall meetings with the president; and finally a stint at the White House National Economic Council where I worked as part of the Social Security reform team.

Bush’s Social Security reform framework had two parts: The first was a benefit change often referred to as “progressive price indexing,” which would have frozen the maximum retirement benefit in inflation-adjusted terms rather than letting it continually increase in the future. Benefits for roughly the poorest third of Americans would have continued to grow over and above inflation, at the rate embedded into current law. Individuals in between the poorest third and those receiving the maximum would have received a slower rate of benefit growth. By itself, progressive price indexing would have fixed about two-thirds of Social Security’s long-run funding gap, while maintaining full benefits for those that need them the most.

On top of this, Bush’s plan would have allowed Americans, on a voluntary basis, to divert part of their 12.4 percent Social Security payroll tax to a personal account similar to a 401(k). These accounts would have prevented Congress from borrowing against the Social Security surplus to fund the government, as well as allowing—but not guaranteeing—individuals to increase their benefits by investing part of their payroll taxes in stocks and bonds. In exchange, individuals who chose personal accounts would give up a proportionate share of their traditional Social Security benefits.

Bush’s reform effort fell short for a variety of reasons, some having little to do with Social Security itself. The Iraq war was faring badly at the time, chipping away at Bush’s political capital. Moreover, congressional Democrats refused to engage on Social Security reform. When a fellow Democrat asked then-House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi when the party would offer its own reform plan, she responded, “Never. Is never good enough for you?

Meanwhile, Republican support for Social Security reform withered as it became clear that personal accounts were not the free lunch that had often been advertised. Rather than precluding the need for tax increases or benefit reductions, personal accounts funded out of the existing payroll tax required that such steps be taken sooner, to compensate for workers diverting part of their taxes to their own accounts.

Fiscally conservative Social Security reform efforts have never recovered. The political center of gravity among Republicans has shifted dramatically to the left under President Donald Trump, embracing a policy stance—no Social Security benefit cuts ever, even for the richest seniors—that in 2005 only the most progressive Democrats held.

But, 20 years later after the failure of President Bush’s reform drive, I asked myself: What might have happened if his reforms had succeeded?

In a new study released by the American Enterprise Institute, I modeled the effects on Social Security retirement benefits if Bush’s plan had been implemented, while incorporating the changes to traditional benefits via progressive price indexing as well as how real-world investment returns since 2005 would have determined the benefits paid from personal retirement accounts.

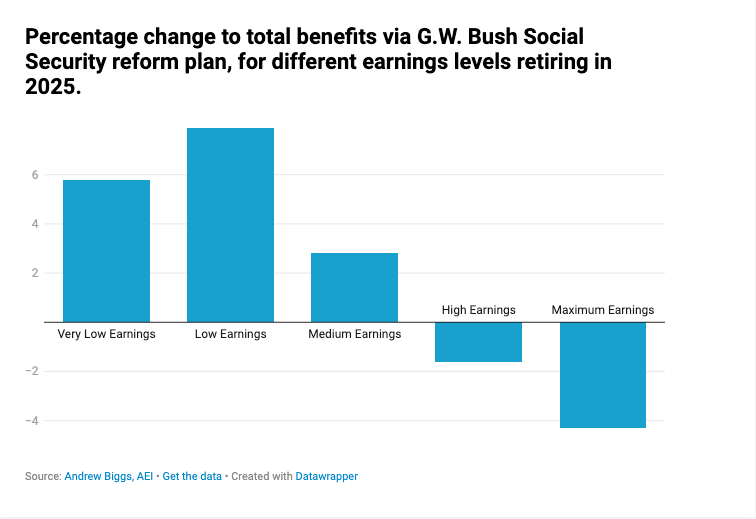

I found that Americans retiring in 2025 who had very low, low, and middle earnings over their careers would have received total Social Security benefits 3 percent to 8 percent above those scheduled in current law. While progressive price indexing reduced benefits for some, personal accounts more than made up the difference.

High-earning employees and those earning the maximum taxable wage and above would have received benefits 2 percent to 4 percent below current law scheduled levels. In these cases, the benefits paid by personal accounts compensated for most of the benefit reductions caused by progressive price indexing.

In a sense, however, the bigger news is that these small positive or negative changes to Social Security benefits would have occurred in the context of a plan that addressed much of Social Security’s long-run funding gap. By seizing the opportunity to act early, George W. Bush’s reforms would have made it easier to restore Social Security to long-run solvency while protecting lower-income Americans who most depend on Social Security benefits in old age. Bush’s reforms would not have fixed Social Security’s entire funding gap, but would have left Americans today facing a much smaller problem.

But, as the 2025 Trustees Report shows, two decades of governmental inaction mean that we face a larger Social Security funding problem today, with fewer and more painful options available to address it.

Now, the fact that Goerge W. Bush’s proposed reforms would have been largely successful does not mean that present-day reforms should simply attempt to revive the Bush blueprint. Bush’s reform drive fell short, for several reasons.

The first is that the American political process is strongly biased against large-scale reforms. I don’t mean simply Bush’s Social Security proposal, but also Bush’s proposed immigration reforms, Bill Clinton’s efforts to fix Social Security, Hillary Clinton’s ill-fated health care proposal, and even Barack Obama’s Affordable Care Act, which despite Democratic supermajorities in Congress passed only by the skin of its teeth.

The unfortunate fact is that the political process and media coverage do not demand that both sides step up with their own plans to fix a given problem. When George W. Bush argued for his brand of Social Security reform, Nancy Pelosi’s “Is never good enough for you?” was treated as good enough, even for a system that faced a multitrillion-dollar funding gap. Any major reform requires a game plan to bring a significant number of opposing-party policymakers on board.

“Instead of proposing difficult-to-understand incremental changes to a Social Security benefit formula that already is difficult to understand, policymakers should begin by outlining what they believe a 21st century Social Security program should look like.”

Second, while personal accounts funded by part of the Social Security payroll tax may have worked if enacted in the past, those days are gone. In 2005, Social Security was running substantial payroll tax surpluses. But this year, Social Security tax revenues will fall $250 billion short of what is needed to pay benefits, with the system relying on redemption of bonds held in its trust funds to make up the difference. The federal government lacks the capacity to cover an even larger Social Security revenue shortfall. While Social Security reform should accelerate household savings for retirement, it should do so with retirement accounts built on top of the existing program.

And third, while progressive price indexing would have moved Social Security toward solvency, it lacked a strong narrative picture of the system we would end up with. Progressive price indexing was a highly technical change to a Social Security benefit formula that most Americans already cannot understand. Moreover, Social Security would still lack any minimum benefit, and would provide weaker protections against poverty in old age than pension systems in other Anglosphere countries.

One of the lessons I took from the failure of Bush’s 2005 reform drive, lessons which shaped the writing of my new book The Real Retirement Crisis, is that Social Security reform should start by stating where it wants to finish. That is, instead of proposing difficult-to-understand incremental changes to a Social Security benefit formula that already is difficult to understand, policymakers should begin by outlining what they believe a 21st century Social Security program should look like.

This would likely produce a retirement system similar to countries such as the United Kingdom, Australia, or New Zealand, where the government provides a solid but limited base of retirement income to prevent poverty in old age. Retirement income on top of this government base is provided through household savings, either mandated (as in Australia) or facilitated (as in the U.K. or New Zealand) by the government.

This model of retirement security provides both stronger protection against poverty in old age and lower budgetary costs, because government pension benefits paid to middle- and high-income seniors are far more limited. For instance, the maximum Social Security benefit—which in 2025 will be $94,836 for a two-earner couple, each earning over about $170,000 annually over their careers—is two to three times greater than the maximum benefits paid in the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, or New Zealand.

The two decades since the failure of George W. Bush’s Social Security reform efforts tell us what might have been, and how costly lost opportunities can turn out to be. But they also point to the need for a different way of thinking about Social Security reform, such that effective policies can not only be devised, but passed into law.