Thankfully cooler heads appear to have prevailed, helped along by the sudden market drop yesterday when it briefly appeared that Powell’s termination really was imminent. Now that it’s “highly unlikely” that he’ll be fired, we can all rest easy, no?

Of course not. Trump is almost certainly going to fire him anyway, assuming he doesn’t resign first.

Patterns.

For all his personal volatility, the president is predictable in how he handles crises.

Take the Epstein debacle. Absurdly, he’s trying to spin the Justice Department’s Epstein files as yet another Democratic “hoax” after MAGA media spent years alleging that proof of a Democratic child-molestation cabal lies within. Much more absurdly, he’s so weirdly insistent about it that he’s renounced the support of fans who persist in believing otherwise.

But he’s just doing what he always does when he feels cornered politically and can’t talk his way out of it, as happened after he lost the 2020 election. “Hoax” is code for “loyalty test.” Trump is trying to reframe the Epstein debate as a matter of the right-wing Us versus the left-wing Them and trusting that loyalty to Us will lead skeptical Republicans to drop a subject that’s uncomfortable for him, grudgingly or not. His approach to this crisis was predictable even if the target of it—his own base!—was not.

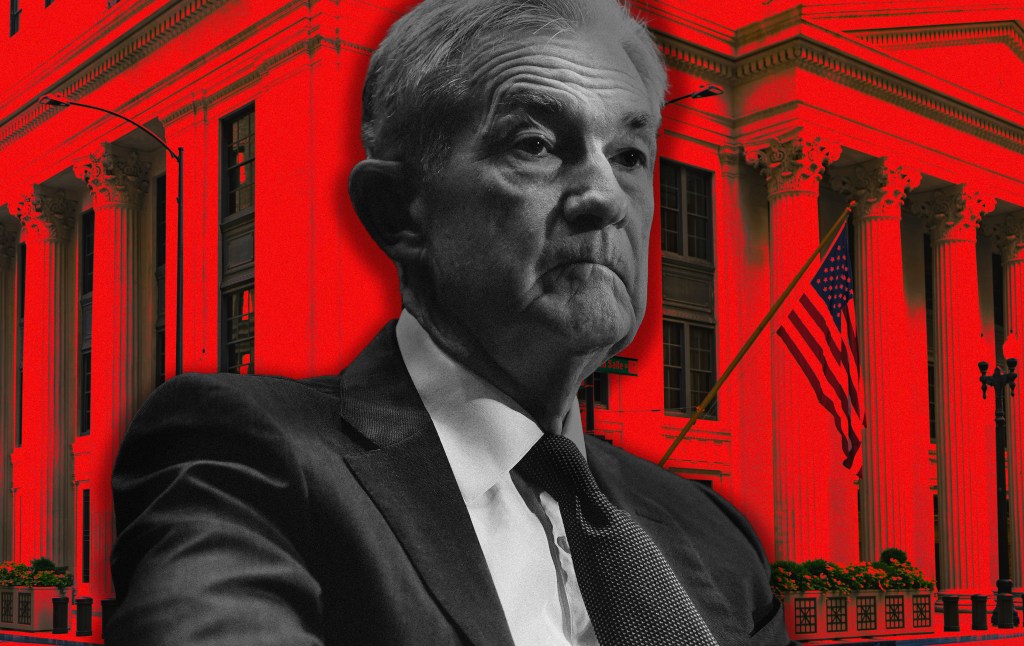

His approach to Jerome Powell is also part of a behavioral pattern. Numerous times in his four-plus years in charge, Trump has nursed intense grudges against “disloyal” deputies until they’ve become vendettas playing out in full public view. No other president has made such a spectacle of trying to hound disfavored underlings out of office.

You can name names as easily as I can. James Comey, Christopher Wray, Jeff Sessions, Robert Mueller: The president browbeat each of them relentlessly until eventually he fired them, as with Comey and Sessions, or convinced them to resign before he had the chance, as with Wray.

“He didn’t fire Mueller,” you say. Right—but he tried. It was only because Don McGahn, his White House counsel at the time, threatened to quit in protest that Trump relented. There are no more Don McGahns around in 2025. I’m sure many administration figures believe firing Powell would be a historic blunder, starting with Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, and I’m just as sure that none will risk their jobs this time to try to stop the president from doing so.

As I sit here, I can’t think of a single Trump official who’s gotten the full vendetta treatment that Powell is experiencing yet hung on to the bitter end of his (or Trump’s) term without quitting or being cashiered. The president’s whole point in humiliating deputies, I’ve always assumed, is to make their lives so unbearable that they’ll resign and spare him the ordeal of having to fire them himself.

Certainly that’s his strategy with Powell. Terminating the Fed chair would place him on thin legal ice and bring down an avalanche of criticism that he has destabilized U.S. monetary policy by politicizing the central bank. While hounding Powell out of office wouldn’t solve the second problem, it would solve the first, which is probably why the daily demagoguery is ramping up.

Do we really think Jerome Powell is prepared to endure 10 more months of it, given the sort of threats he and his family are likely receiving from hardcore MAGA cranks as a result? Even if he is, do we think Donald Trump has the patience to endure 10 more months of Powell ignoring his demands to cut rates if and when the economy slides into a tariff-driven slowdown?

There’s no way. We’re talking about a guy who once dashed off an out-of-the-blue memo giving the Pentagon two months’ notice to pull everyone out of Afghanistan. He’s a little impulsive, you may perhaps have noticed at some point since June 2015. If he’s already having letters about firing Powell drafted and showing them off to toadies like a trophy, it’s unimaginable that he won’t pull the trigger during some economy-related tantrum between now and May 2026.

Besides, I think the Powell saga reflects another Trump pattern that’s reasserted itself lately, this time having to do with trade.

Return to form.

The extended pause on “Liberation Day” tariffs is almost over so the White House has resumed threatening steep levies on U.S. trade partners. Not just partners with whom we’re running a trade deficit, either, and sometimes not even for reasons having to do with trade.

Markets don’t care. The S&P 500 plunged after “Liberation Day” but is roaring along as Trump flirts with tariffs every bit as hair-raising as the ones he briefly imposed in April. The reason is obvious: Investors expect that he’s going to TACO his way out of imposing them as the end of the pause approaches.

I don’t think he is. He sure sounds serious about sticking our friends in Japan with a 25 percent tax on their imports, for instance. To all appearances, he’s about to rerun the same “Liberation Day” experiment that he ran this past spring in hopes of getting a different result.

The “TACO” barbs that have gotten under his skin may have something to do with his resolve, as there’s no surer way to goad a strongman into proving his strength like calling him a wimp. But I suspect Trump feels encouraged by the robust post-“Liberation Day” market recovery to revisit his grand plan for the economy. His mistake in April was moving too abruptly in launching his trade war, he might believe. Now that he’s given investors time to price in the costs of protectionism, the moment has arrived for a second try.

Simply put, he may be convinced that the economy is resilient enough for him to start screwing around with tariffs again. And if he’s convinced of that, why wouldn’t he also be convinced that it’s resilient enough for him to pink-slip Jerome Powell without causing a financial Chernobyl?

His approach to Powell this year mirrors his approach to tariffs, in fact, in that in both cases he moved aggressively before hastily retreating and then slowly inching back toward his initial position. Remember that, as far back as mid-April, Trump said of Powell that his “termination cannot come fast enough!” after the Fed chair made unhappy noises about his trade policy. Someone (probably Bessent) must have pulled him aside after that and warned that decapitating the Fed would cause already jittery bond markets to go haywire, so the president clarified the following week that he had “no intention” of firing its chairman.

Now, at the very moment that it’s making another run at a trade war, the White House is coincidentally also making another run at Jerome Powell. An ill-advised blitz attack, then a cooling-off period to give Americans time to adjust, then a renewed attempt at the original goal: If that’s the pattern on tariffs, why wouldn’t it also be the pattern on firing Powell?

Guardrails.

Powell is different, you might say, because the president knows he can’t “pause” his firing once it’s been ordered the way he can with new tariffs. If the prospect of Donald Trump dictating interest rates to a chair-less Fed causes markets to melt down, there’s no way to undo that damage. Which, logically, should deter Trump from taking a chance on inflicting it.

It should, right. But remember who we’re talking about here. The predictable market reaction to “Liberation Day” should have deterred Trump from launching a thermonuclear trade war but it didn’t, did it? When he has his heart set on something, he’ll find a way to rationalize the risk.

Which, frankly, won’t be hard for him in the case of firing Powell. He’s the kind of person still capable of believing in 2025 that tax cuts “pay for themselves.” So he’s probably also capable of believing that installing a stooge as Fed chair to slash interest rates to zero will ignite enough growth to more than offset investors’ loss of confidence in a banana-republic-ized United States.

Okay, you might respond, but Powell is still different because legally Trump can’t fire him. Comey, Sessions, Mueller, and Wray were all executive officers directly answerable to the president. The Fed chairman is not. The White House might be willing to cause upheaval in markets for the sake of replacing Powell with someone more compliant. But why would it take that risk for a gambit that’s likely to end with Powell still on the job?

That’s a solid point, made more solid by a Supreme Court ruling less than two months ago. In a decision released in May, the court went out of its way to distinguish the president’s authority to fire officers at independent agencies like the National Labor Relations Board from his alleged authority to fire officers at the Fed. “The Federal Reserve is a uniquely structured, quasi-private entity that follows in the distinct historical tradition of the First and Second Banks of the United States,” the majority warned. Hint hint: Don’t try to fire Powell.

Would Trump take that hint, though? The court has sided with him a bunch lately on questions of executive authority, most notably last month when it restricted the power of federal district courts to enjoin his policies nationally. Because Trump understands Supreme Court rulings purely in terms of whether the Republican majority is feeling loyal to him or not, he might surmise that the moment is ripe to try his luck with firing Powell. Maybe they’ll swallow his nonsense about renovation “fraud” amounting to good cause for termination under the Federal Reserve Act.

Or maybe the White House suspects the case won’t get that far. Perhaps they expect that Powell would conclude it’s better for the country and for global markets for him to accept his termination than to litigate the matter in court for months, leaving leadership of the Fed under a legal cloud and investors drowning in uncertainty. The president won’t be deterred by civic-minded considerations like that. Powell might be.

In the end, maybe the best argument that Trump shouldn’t bother trying to fire him is that doing so almost certainly won’t achieve what the president wants. The Fed chairman doesn’t set interest rates unilaterally; the Federal Open Market Committee, a board of 12 members over which the chairman presides, does so via majority vote. If Trump wants to dictate rates, he’d have to replace multiple members with political flunkies. Does the White House have the stomach to try that?

Maybe? Put it this way: If any White House does, this one does.

But even if it doesn’t, Trump might fire Powell simply to scratch his itch for “retribution,” not to try to force a rate cut. That’s what he did with Jeff Sessions, who was canned eventually for having failed to recuse himself from the Russiagate probe even though his dismissal did nothing to end that investigation or to place it under the president’s control. Vendettas aren’t about accomplishing policy goals, they’re about anger, and Trump was angry at Sessions.

Just like he’s angry at Jerome Powell.

Politicization.

If what we’re worried about in all this is the president politicizing monetary policy then to some degree it doesn’t matter at this point if he terminates Powell.

He’s trying to influence the Fed’s decisions on interest rates by intimidating its highest-ranking official. No matter what happens now, investors will wonder whether his jawboning successfully introduced political considerations into its calculus.

If the Fed lowers rates, it’ll be suspected of having caved to presidential pressure. That will encourage Trump to turn up the political heat in hopes of browbeating it into additional cuts. And that in turn might drive up long-term bond rates amid fears that politics, not sound economic reasoning, will increasingly inform U.S. monetary decisions in the future.

If the Fed declines to lower rates, the GOP will accuse it of acting not out of fear of inflation but out of fear of being perceived as capitulating to the president. Any economic downturn over the next three years will be blamed, ironically, on the juvenile grudge that Powell and the Fed’s board supposedly harbor toward Trump. Again, investors will be led to believe that politics rather than economics is driving monetary policy.

The Federal Reserve will end up caught in the same trap that Trumpists have created for the federal judiciary. In the spirit of their leader, their primary intellectual frame for understanding government action is loyalty and their primary method for influencing it is intimidation. So when some official actor like a judge—or the Fed—issues a ruling, partisans on both sides tend to explain it in those terms. If the ruling is favorable to Trump, it was motivated by right-wing tribal allegiance and/or fear of “retribution.” If it was unfavorable, it was motivated by disloyalty and/or the desire to restrain MAGA. Either way, the calculus is assumed to have been improperly political.

Respect for institutions can’t exist in an environment like that and increasingly it doesn’t, even on the left. Jerome Powell and the Federal Reserve are no exception. Trump is going to fire him, just as he always ends up firing perceived “enemies.” He might as well get on with it.