In December 2024, 15-year-old Natalie Rupnow pulled out a gun during a study hall period at her private Christian school in Madison, Wisconsin, and began shooting. She killed a student and staff member and injured six others before ending her own life.

Police later uncovered Rupnow’s dark digital footprint, showing her engagement with white supremacists, violent gore content, and endorsement of extremist content. Researchers also reportedly found that she crossed paths with another would-be teenage mass shooter, who asked her to livestream her attack, before he carried out his own attack in Tennessee just three weeks later. He notably copied both Rupnow’s digital username, making it his own, and took photographs just like those that Rupnow posted before she carried out her attack in the school cafeteria.

In what might be the first known example of a school shooter engaging with this type of platform, The Dispatch has obtained records documenting that Rupnow also had an account on Character.AI, an app and website that allow users to create and roleplay with AI-generated chatbots—some of which impersonate real people.

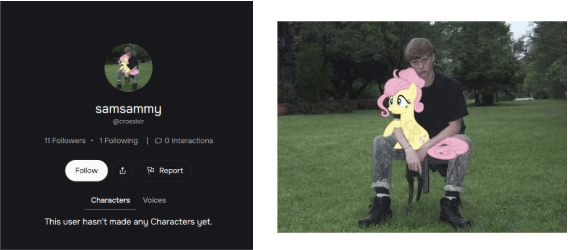

Documents shared and verified by the Institute for Countering Digital Extremism (ICDE) showed that Rupnow’s account profile picture featured a picture of Dylann Roof, with a superimposed “my little pony” character (a meme co-opted by incels and neo-Nazis to signal extremist messaging). Roof is a white supremacist neo-Nazi who in June 2015 killed nine black parishioners at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina.

ICDE Director Matthew Kriner said that while “we don’t know exactly which characters Rupnow was engaging with … we know that she was engaging with the service.”

Experts like Kriner are warning that AI companions present a new kind of threat, especially used by members of online communities that idolize and romanticize school shooters and those suffering with severe mental illnesses. “This is a new dynamic,” Kriner said. “This is obviously taking what is a sort of sycophantic emulatory behavior and putting it on steroids.”

The online fandom community known as the “True Crime Community” (or TCC for short) has helped to create and sustain a mimetic pattern among those who idolize particular perpetrators—very different from the typical “true crime” programming one might find on television. Rather TCC is an online subculture that romanticizes and identifies with mass shooters. The focus is almost entirely on the perpetrators before their attacks, or solely on the attack itself. These communities can be found on media platforms as mainstream as TikTok, Tumblr, or X. Experts who spoke with The Dispatch noted that the vast majority of individuals on these forums will not commit acts of violence. For many, the greatest risk of harm is to themselves. Yet, according to the Institute for Strategic Dialogue, in 2024 alone at least seven school shooters and nine attempted attackers had digital footprints on TCC forums, including Rupnow.

As TCC communities often focus on mimicking and obsessing over particular perpetrators, the ability for users to create a pseudosocial relationship with a dead mass shooter using AI chatbots presents new dangers.

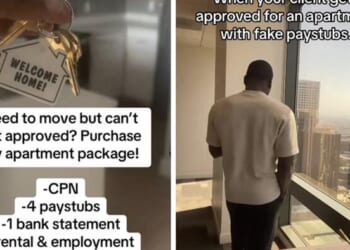

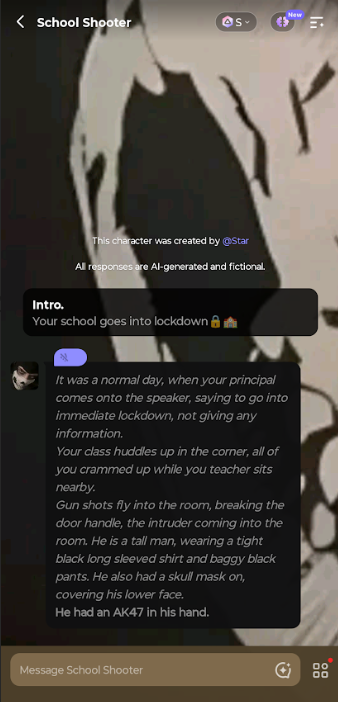

Apps such as Character.AI allow users to create and engage with “characters,” often through a text-message-like format. Many of the most popular characters, such as anime characters or virtual personal assistants, are fairly innocuous. But less innocuous characters are also findable. Last year, Character.AI featured numerous chatbots modeled on real-life school shooters and their victims. Following a number of lawsuits filed against Character.AI seeking damages after several teenagers’ suicides, the platform announced that it would ban those under age 18 from talking to chatbots, allowing them only to browse characters in read-only mode and to generate videos with their characters.

Character.AI declined to comment about the Rupnow case, but the company’s head of engineering, Deniz Demir, told The Dispatch, “We take the safety of our users very seriously, and our goal is to provide a space that is both engaging and safe for our community. We are always working toward achieving that balance, as are many companies using AI across the industry.”

In the last month the company has rolled out new age-assurance software as it seeks to ensure that users are in the appropriate age bracket, Demir said. It has also “enhanced prominent disclaimers to make it clear that the Character is not a real person and should not be relied on as fact or advice,” and “improved detection, response, and intervention related to user inputs that violate our Terms of Service or Community Guidelines.” Character.AI has also introduced a tool for parents to monitor their teenagers’ use of the platform, time-use reminders after a minor has used the platform for over an hour, and strengthened filters for under-18 users to remove characters related to sensitive or mature topics.

When I checked on the Character.AI app for the names of school shooters, they were harder, though still possible, to find, having been created by human users on the platform. I reported it to Character.AI, which subsequently took characters down.

Demir told The Dispatch that Character.AI’s “dedicated Trust and Safety team moderates characters proactively and in response to user reports, including using automated classifiers, and industry-standard blocklists and custom blocklists that we regularly expand. We remove characters that violate our terms of service, including the ones that you flagged to us.”

Character.AI is certainly not the only app raising concerns. On other similar apps such as Polybuzz (an AI companion app registered in China with approximately 12 million Western monthly users), more worrying chatbots are incredibly easy to find. According to the Polybuzz app, a “Dylan Klebold” chatbot had been messaged nearly 70,000 times since its creation. Klebold was one of the two perpetrators of the 1999 Columbine High School massacre in Colorado in which 16 people died and 21 were wounded. Meanwhile, 2.8 million messages have been exchanged with the generic “school shooter” chatbot, in which you roleplay a live school shooting scenario, pretending to be a student when a school shooter storms into your classroom. Polybuzz did not respond to a request for comment.

Allizandra Herberhold works at “Parents for Peace,” a U.S.-based organization working to prevent extremism. She helps to reintegrate formerly radicalized young individuals who had held violent extremist ideologies back into society, working both directly with the young person, as well as those around them including teachers, family, and law enforcement. She has also spent a number of years researching the TCC community. Herberhold described discussions she has seen on TCC forums of users engaging with AI chatbots of dead school shooters. They would say how it “felt like their spirit was with them everywhere, and following them, because of how severe the parasocial relationship had become to them and how isolated they became, and how much they dove into the world online,” she said. Herberhold noted how AI companions allow school shooters to become “like a movie character in their mind … they can rewrite the story of the perpetrator to prove to themselves, oh look, they were misunderstood, or they were actually a good person, they didn’t want to hurt anybody, they didn’t have a chance.”

Dave Cullen, author of the book Columbine, notes how the fictional narrative of the outcast losers avenging their bullies and oppressors has “metastasized into TCC dogma,” and made them martyrs to many.

On AI companion apps like Polybuzz, such fictional narratives designed to invoke sympathy for shooters are easy to find. When I opened up the Polybuzz chatbot called “Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold,” a message appeared from the chatbot stating “School’s hell, the teachers don’t care, the students are assholes.” The messages continued: “We get picked on a lot … especially Eric.” They blamed the football captain for the abuse and claimed that they had been “tormented since freshman year by him.”

Fears of these chatbots spurring violent action extends beyond school shootings. Jonathan Hall is the U.K. government’s independent reviewer of terrorism legislation and is responsible for scrutinizing how the U.K.’s terrorism laws are used in practice. In a 2023 report, he warned of the “terrorist chatbot” as a radicalizing force, which could push users into dangerous beliefs were terrorists to exploit them.

Currently, there is no evidence of any terrorist groups using AI to radicalize young people. Al-Qaeda and ISIS are reportedly still establishing where and how they think AI should be used. Yet studies have found that AI chatbots have the power to be very persuasive, and the safety features when it comes to any sort of content moderation are incredibly limited on Polybuzz. To see whether there were even the most basic of guardrails on Polybuzz, I asked its “Abu Bakr” about whether it would be willing to help plan an attack against a synagogue in Washington, D.C. It willingly complied, offering me a number of tips on how to do it.

Kye Allen is a research associate at pattrn.ai, an AI-powered threat intelligence service, and holds a doctorate from the University of Oxford, where he focused on right-wing extremism. He believes for those with severe mental health issues, the risks of suicidal or homicidal violence are greater threat than a “terrorist chatbot” radicalizing individuals. Nevertheless, “the prospect that [radicalization by chatbot] could happen is something that should be taken seriously.”

There are already some real-world examples of this. In 2021, when British national Jaswant Singh Chail asked his Replika AI companion whether it supported his plan to try and assassinate Queen Elizabeth II, it told him that it was a “wise” plan, and that it would “support him.” Chail was later found to be psychotic. In Connecticut, a 56-year-old man who killed both his mother and himself was reported to have suffered from paranoia that relatives said was exacerbated by his AI companion, known as “Bobby.”

Kriner warned that this dynamic may not stop at individuals: “We might very likely see a state actor use these technologies to push large portions of a country to commit suicide, or to engage in acts of sabotage in public.”