Two weeks ago, a man rammed his truck into a Latter-day Saint meetinghouse in Grand Blanc, Michigan, shattering the serenity of Sunday worship service. The attacker viewed the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and its members—“Mormons,” as he referred to them—as the “antichrist.” Less than a week before the attack, the perpetrator reportedly went on an “anti-LDS” tirade to a local city council candidate, Kris Johns, who was out canvassing. “It was very much standard anti-LDS talking points that you would find on YouTube, TikTok, Facebook,” Johns said.

After smashing his car into the church, the gunman set the chapel ablaze and opened fire on fleeing parishioners, killing four and wounding at least eight others. In the wake of such an atrocity, survivors understandably struggled to find words to capture their emotions. “It’s just devastating. …We were worshiping our Savior Jesus Christ and then this happens,” a congregant named Paula said in the aftermath. “My church is gone. I joined the church 38 years ago in that building, and now it’s gone.”

Nearly two centuries earlier, Joseph Smith walked the charred rubble of the Ursuline Catholic convent, burned to the ground in 1834 at the hands of an anti-Catholic mob outside Boston. If such an atrocity could happen on the selfsame soil where English separatists fled for religious refuge and patriots bled to secure it, Smith surely feared for his own persecuted flock in the western reaches of Missouri.

“The Mormons must be treated as enemies,” read Executive Order 44, issued by Missouri Gov. Lilburn Boggs in 1838. They must be “exterminated” or “driven from the state. … their outrages are beyond all description.” Smith petitioned the federal government for redress, traveling to the White House in person. After Smith presented his people’s plight, President Martin Van Buren responded, “What can I do? I can do nothing for you. If I do anything, I will come in contact with the whole state of Missouri.”

A central paradox in the early history of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is that the same laws and freedoms that were essential to its founding—providential, even—were seemingly insufficient to fully protect it from abuse.

There’s a common myth, as Latter-day Saint historian Spencer McBride has pointed out, that “the American Revolution ushered in universal religious freedom.” But any perusal of American history as it relates to Catholics, Jews, Muslims, or numerous other minority faith traditions in the United States quickly dispels this notion. Latter-day Saints provide an easy “Exhibit A.”

After the Saints painstakingly documented the atrocities of Missouri—the violence, the burnings, the stolen land, the rapes, and the murders—the church petitioned anyone who would listen and many more who wouldn’t. Smith sent a handful of letters to potential presidential candidates, seeking an answer to how they would protect the Saints if elected.

He received a few responses, but none proved satisfactory. Some pointed to the states’ rights doctrine, holding that the Bill of Rights was simply unenforceable against the states. Only the 14th Amendment, ratified after the Civil War, would eventually change that. But even then, the Supreme Court didn’t rule that the First Amendment applied to the states until the 20th century. Faced with these disappointments, Smith decided to take a different approach, launching his own bid for the presidency in 1844.

Smith’s campaign platform called for the reestablishment of a central bank, the abolition of slavery, radical reforms to penitentiaries, and, most significantly, protections for religious freedom.

“If it has been demonstrated that I have been willing to die for a ‘Mormon,’” Smith preached, “I am bold to declare before Heaven that I am just as ready to die in defending the rights of a Presbyterian, a Baptist, or a good man of any other denomination; for the same principle which would trample upon the rights of the Latter-day Saints would trample upon the rights of the Roman Catholics, or of any other denomination who may be unpopular and too weak to defend themselves.”

In the midst of his bid for the presidency, Smith and other church leaders were awaiting trial in Illinois on charges of “inciting a riot” when a mob of more than 100 men—faces smeared with gun powder—stormed the jail. The attackers shot Smith, who fell from the second-story window in a hail of bullets, proclaiming, “Oh Lord, my God!”

This dark hour marked the first assassination of a presidential candidate in United States’ history. The Latter-day Saints lost their beloved “prophet, seer, and revelator.”

This episode underscores the antebellum struggle to fully realize the promises of religious freedom set out at the nation’s founding. That struggle, of course, continues as we see alarming rates of antisemitism and other forms of religious bigotry, violence, and discrimination. But there’s reason to be hopeful about religious freedom’s future, not just for protecting faith but also for helping it flourish. Social science is establishing with increasing granularity the varied ways in which religion remains essential to America’s long-term prosperity and well-being.

The highly religious—those who don’t just attend worship services but also engage in what scholars at the Wheatley Institute call regular home-centered religious practices—are more likely to report happiness and meaning in life. According to Yale professor Samuel Wilkinson, the highly religious tend to have better mental health and less suicidality. They are also more likely to marry and marry younger. They have more children and sustain marriages marked by emotional closeness, shared decision making, and greater sexual and marital satisfaction.

Perhaps this doesn’t seem too remarkable. But if the population broadly continues to trend in a different direction—fewer marriages and children, worsening mental health, and mounting social isolation—the divergence will only grow. To put it bluntly: The highly religious are replacing themselves. Most other groups in America are not. In a very literal sense, as Jesus said in the gospels, the religiously meek are inheriting the earth. Consequently, the nation’s demographic fate will be tied at least in part to the health of America’s religious ecosystem.

Latter-day Saints provide something of a case study in the fruits that come when prosocial faith is provided space to live out its ideals.

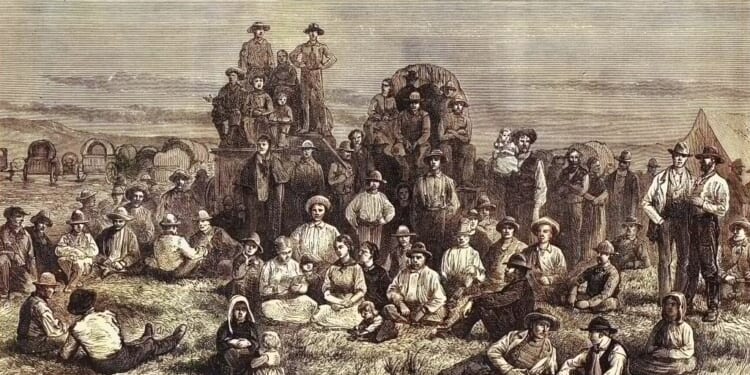

After fleeing Missouri and Illinois—and after the death of Joseph Smith—the Latter-day Saints were once again uprooted. In one of America’s largest overland exoduses, they left for the Rocky Mountains in a final bid to find freedom beyond the traditional bounds of their homeland.

Again, religious freedom was about survival. But the Saints also challenged and refined the contours of America’s first freedom, from the polygamy cases of the late 19th century to Utah’s battle for statehood and the four-year hearing over the election of Latter-day Saint Apostle Reed Smoot in the U.S. Senate.

More recently, Latter-day Saints have linked arms with broad coalitions of faith groups to advance congressional and judicial decisions pertaining to religious freedom in the 20th and now 21st centuries. The late Utah Sen. Orrin Hatch was a central champion of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act in 1993, which prohibited the government from substantially burdening the free exercise of religion. Former Sen. Mitt Romney was vital to amending the Respect for Marriage Act in 2022 to include robust religious freedom protections supported by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the Seventh-day Adventists, the Jewish Orthodox Union, and the Coalition for Christian Colleges and Universities, among others.

Though not without conflict—including the threat of a military confrontation with the federal government in 1857—the Latter-day Saints found in Utah a promised land—their own vine and fig tree. And today, the state contains a larger-than-usual concentration of Latter-day Saints. The impact of this critical mass of highly religious citizens often manifests itself in specific outcomes.

This spring, U.S. News & World Report named Utah the “best state” in the union for the third year in a row. The report looks at a variety of factors, including job prospects, education, the economy, and overall quality of life, among others.

Utah has a higher percentage of children raised in a two-parent household and greater social cohesion. It has higher rates of upward mobility, especially for young women, according to research from Harvard’s Raj Chetty.

Utahns, on average, consume less alcohol and tobacco. Drunk driving fatalities are low and life expectancies high. Utah’s population is one of the youngest, its economy is one of the strongest, and its poverty rate is among the lowest in the nation. Utah, predictably, has the highest rates of church attendance, volunteerism, and charitable giving.

The benefits of highly religious individuals broadly—and not just Latter-day Saints—are well documented. As the country faces a slew of distinct challenges, including social isolation, political polarization, declining mental health, and decreasing marriage and birth rates, America needs strong and proven antidotes. Religion is one of them.

Most Latter-day Saints have grown up hearing some version of a prophecy that the U.S. Constitution will someday hang “by a thread,” and the church would play a role in preserving it. To quote Joseph Smith: “This people will be the staff upon which the nation shall lean.”

After the Grand Blanc shooting, David Butler, a member of the church, was moved by his faith to start a fundraiser to support the widow and son of the perpetrator. To date, the fundraiser has raised more than $380,000 in less than two weeks. Many of the donations are relatively modest contributions of $10, $25, or $50.

Some donors wrote notes, such as this one, from Chris: “I’m so sorry for what your family is going through. It’s so hard to have to deal with consequences of the choices our loved ones make. I hope the money helps, but mostly I hope you can feel the compassion we have for you.”

David French, writing for the New York Times, applauded the effort and quoted writer Kelsey Piper who said on social media that if America is to survive, it will be because people forgive when “they should never have had to.”

To that sentiment French adds the following: “America has witnessed two remarkable acts of forgiveness in the last month. Erika Kirk forgave the man who killed her husband. Latter-day Saints loved the family of the man who massacred their brothers and sisters. A nation that produces such acts of such love is a nation that still has life. It’s a nation that still has hope.”

I’m not qualified to judge prophecy or assess its fulfillment. But after witnessing these gestures, I too feel as if I glimpsed alongside Piper and French a vision for how our fractured, polarized republic might piece itself back together. I also see hints of what it might mean for Latter-day Saints and all people of goodwill to become a “staff upon which the nation shall lean.”