You’re reading Capitolism, Scott Lincicome’s weekly newsletter on economics. This edition has been unlocked for all readers. To read all of our reporting and analysis, become a Dispatch member today.

Wonks like me rarely weigh in on a case before the U.S. Supreme Court, but the current challenge to President Donald Trump’s “emergency” tariffs is so extraordinary that it demanded I make an exception. As has been widely reported, the case (Trump v. V.O.S. Selections, Inc. & Learning Resources Inc. v. Trump) raises profound legal questions about the scope of executive power—in particular whether the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) lets the president singlehandedly rewrite the entire the U.S. tariff code for effectively any reason, even though the Constitution establishes that tariff-setting is the exclusive purview of Congress. And, as we’ve discussed here, the case also matters greatly for the thousands of American companies facing new, unpredictable, and in some cases fatal taxes on their import-dependent business models—businesses that were operating perfectly normally and lawfully before Trump decided to go Full Tariff Man earlier this year.

Those issues are important, of course, and many smart and experienced people wrote to the court last week to explain why it should invalidate Trump’s IEEPA tariffs on those bases. (The hilariously imbalanced list of pro- and anti-tariff submissions is itself quite telling.) But my Cato Institute colleagues and I picked another topic altogether for our brief: the bizarrely inaccurate policy claims coming from the Trump administration and its lawyers—in particular, their repeated statements to the court that disaster would befall the nation’s economy and foreign policy if the tariffs were to be struck down.

It’s all pretty nuts. As we’ll discuss today, however, it nevertheless warranted a forceful and official response because this case, oral arguments for which are set for November 5, is a really big deal.

Another Great Depression? Cmon, Man.

The government’s policy claims are not only inaccurate but also ridiculous. I won’t go through all 10 issues we covered in the brief, but here are probably the biggest ones:

A ruling against the IEEPA tariffs would not lead to “financial ruin” or “a 1929-style result” for the economy more broadly. Tariffs are indeed raising billions of dollars in new federal revenue, but—leaving aside that most of these taxes are being paid by Americans—the totals are not a fiscal game-changer. For starters, even on a simple “static” basis (meaning no other changes to policy, spending/revenues, or the economy), customs duties were just 6.4 percent of total receipts when the tariffs were fully in effect in the May-September period, and IEEPA tariffs were a little more than half of this amount (around $90 billion). Even these figures, moreover, overstate the tariffs’ near-term fiscal effects because the tariffs reduce other federal tax receipts, thanks to 1) importing businesses deducting tariff payments from their taxable income (thus mechanistically reducing corporate and individual income tax amounts), and 2) slower economic growth and the smaller tax base that the tariffs create. “Dynamic” revenue calculations taking these factors into account thus show IEEPA tariffs raising billions less each year than what a static calculation shows.

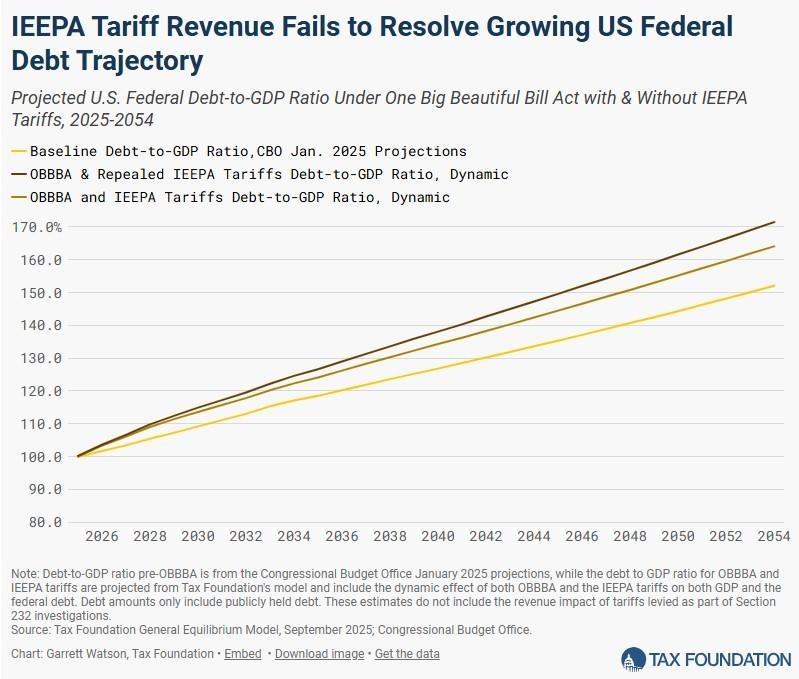

Just as importantly, the tariffs’ long-term impact is relatively small because other U.S. policies, especially entitlements, “predetermine the federal government’s long-term fiscal trajectory and will dwarf the IEEPA tariffs’ revenue effects.” Thus, the Tax Foundation has calculated that—from 2025 to 2055—U.S. public debt would rise from 99.9 percent of GDP to 164.1 percent with the IEEPA tariffs and to 171.5 percent without them. My Cato Institute colleague Dominik Lett finds much the same over the next 10 years.

The government claims that, “With tariffs, we are a rich nation; without tariffs, we are a poor nation.” In reality, we’re facing a crippling debt situation either way.

The administration’s predictions of “catastrophic consequences” for the broader U.S. economy are also silly. As we explain in the brief, the tariffs’ relatively modest fiscal effects explain why several studies of Trump’s spring 2025 tariff announcements found that contemporaneous movements in Treasury markets were driven mainly by economy-wide and tactical factors, not bond investors’ expectations of transformative tariff revenues. The government’s bizarre claim that nixing the tariffs would force Washington to “pay back” foreign investments promised as part of Trump’s trade deals—investments that aren’t assured, haven’t even started, and would create no government obligations when/if they do—is ludicrous on its face. And readers of Capitolism surely know by now that economic analyses and business surveys consistently show that invalidating the tariffs—and eliminating the massive uncertainty unique to the broad and vague IEEPA—would modestly help, not majorly harm, the U.S. economy. For these and other reasons, tariff pauses and adverse court decisions have been immediately followed by stock market gains, while new tariffs are typically accompanied by modest selloffs. (The U.S. economy is huge, of course, so we should never expect massive stock market moves either way.)

A ruling against the IEEPA tariffs wouldn’t implode U.S. trade and foreign policy. The administration is on similarly shaky ground regarding foreign affairs. First, its claims that U.S. trade deals simply couldn’t have been completed without IEEPA tariffs flies in the face of decades of history saying otherwise:

Since IEEPA’s 1977 enactment, the United States has completed 14 comprehensive regional and bilateral Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) with 20 countries as well as the multilateral Tokyo Round and Uruguay Round Agreements (establishing the World Trade Organization (WTO)) with 165 other countries currently. In virtually every agreement, U.S. trading partners lowered their average tariffs on American exports more than the U.S. did on foreign exports. None of these successful agreements were negotiated using IEEPA tariffs or the threat thereof.

Among these agreements is the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement that Trump himself negotiated and signed, and that was hardwired into U.S. law by congressional passage. As we go on to explain, these past U.S. trade agreements were also much better substantively than Trump’s new IEEPA deals for several important reasons. Not only were they approved by Congress (and thus clearly lawful!), but they were also more durable, comprehensive, and economically significant than the vague and unenforceable “term sheets” Trump has inked this year. The idea that U.S. trade policy couldn’t function without IEEPA tariffs simply doesn’t pass the giggle test. (And I was pleased to see several former U.S. government officials basically say the same in their amicus briefs, too.)

The government also errs when claiming that IEEPA tariffs are an essential part of U.S. foreign policy. As we show, the U.S. government has negotiated and ratified hundreds of real treaties (538, to be exact) since 1977 and never once used IEEPA tariffs to do it. Nor were the tariffs involved in any other pre-2025 diplomatic successes, including the Abraham Accords that normalized relations between Israel and several Arab nations, and that Trump himself considers one of his crowning foreign policy achievements. If anything, there are emerging signs that the IEEPA tariffs are pushing allies away from the United States, including and especially with respect to China. See, for example, this brand new dispatch from Southeast Asia on how former U.S. friends are playing nice with Trump but “rapidly seeking to reduce trade with the U.S. after [he] saddled them with sky-high tariffs earlier this year—a surrender of influence in the region to America’s number one adversary.” Also this week, these same nations deepened their free trade agreement with China, which was already each economy’s biggest trading partner.

Major tariff refunds are not only doable but have been done before. Finally, the administration is wrong to imply that refunding billions in ill-gotten IEEPA tariffs would be administratively impossible or otherwise cause a “significant disruption” in the government. In fact, the Trump team has quietly acknowledged the feasibility of duty refunds in this very litigation (when telling courts that pausing duty collections was unnecessary), and—even more importantly—U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) has issued significant duty refunds when the law or courts demand it. The duty refund process can be difficult—especially for small importers that don’t have lawyers and customs brokers on standby—but it can also be easy and automatic:

U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) has issued broad, automatic refunds when required to do so. For example, the March 2018 renewal of the Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) program required both retroactive application to January 1, 2018 and the refund of any duties collected on GSP-eligible merchandise…. In response, CBP issued Cargo Systems Messaging Service (CSMS) 18-000296 providing for the automatic processing of such refunds for all importers who had (1) used the agency’s Automated Broker Interface and (2) included the GSP Special Program Indicator prefix with the tariff number on their electronic entries. For these entries, CBP explained, refunds “will be processed automatically by [CBP] and no further action by the filer is required to initiate the refund process”—a process CBP expected to complete in approximately three months. CBP issued an even larger volume of automatic, retroactive refunds for the 2013—2015 lapse of GSP, and a similar coding system remains in effect.

As we go on to explain, CBP could use a similar system to refund most of the IEEPA tariffs because the agency has assigned at least one special tariff code (“Chapter 99”) to all imports subject to the tariffs. The agency could use these codes to find all relevant entries and refund IEEPA-related duties automatically—with most refunds simply direct-deposited right into importers’ bank accounts. The alternative—involving tons of paperwork, millions of transactions, and maybe even separate lawsuits for every aggrieved U.S. importer—would be a big mess. So, the only question here is whether the government wants such problems (to make it hard for U.S. companies to get their money back), not whether blanket refunds are possible. They are.

So, Why Weigh In at All?

The administration’s claims are so fantastical and nonsensical that one could be forgiven for simply dismissing them with little more than the usual Twitter snark. (And, to be honest, that was my original plan, too.) However, for those with longer memories the government’s language raises suspicions: Is this howling actually a strategic move to push the court to side with the administration, even when the law says otherwise? As legal experts have documented (and betting markets show), the administration is a slight underdog in the tariff litigation, and there’s precedent for using the president’s bully pulpit to paper over a Supreme Court case’s legal deficiencies. As you may recall, for example, the Obama administration and its allies also predicted big problems and engaged in a not-so-subtle pressure campaign when the fate of the president’s signature policy, Obamacare, was before the court in 2012. Many legal and political commentators have since speculated that the approach was indeed effective in pushing Chief Justice John Roberts to uphold the law (in extremely dubious fashion)—not for legal reasons but political and institutional ones.

To be clear, I have no idea whether the Trump team is pursuing a similar strategy here—at least as a Plan B in case its main legal arguments fail. (Reason’s Supreme Court-watcher Damon Root suspects they are.) Yet, with recent history in mind, we decided that the administration’s policy claims needed an official correction from people who know better, in the off chance that the administration’s doomsaying really could shift the court’s attention away from the legal arguments that should dictate the case’s outcome. Such claims might also manufacture public outrage in response to a court ruling against the tariffs, so we’re following up with op-eds and blog posts, too.

Maybe this risk is low, but the stakes here—on the law, the economics, and our system of constitutional governance—are big enough that we didn’t want to take any chances. As we discuss in the brief, for example, Trump’s IEEPA tariffs jettison the long-established system of U.S. tariff-setting—formal cooperation between the executive and Congress that’s been used more than 200 times to create a stable and predictable baseline tariff code (the “Harmonized Tariff System of the United States”)—for a new system in which a single person can declare an “emergency” for any reason and then completely rewrite the entire tariff code, covering thousands of products and hundreds of countries, however and whenever he wants. Presidents do have the power to apply duties on top of these baseline tariffs for certain goods or places, but they’ve never just scrapped the entire base itself (which includes all the trade agreements previous presidents and Congresses have codified into U.S. law). Yet that’s exactly what Trump is doing—repeatedly. And it’s just what he promised he’d do on the campaign trail last year.

Even this example, however, doesn’t really do justice (pun!) to the chaotic, dictator-like power that the government’s expansive view of IEEPA unlocks. Indeed, just as we were filing the brief, Trump announced brand new tariffs on Canadian imports—presumably under IEEPA—because the government of Ontario dared to run an advertisement featuring anti-tariff quotes from Ronald Reagan atop a bunch of scenes of Americans and Canadians happily coexisting. Never mind, as has now been widely documented, that the quotes were real, that Reagan strongly supported free trade with Canada (and generally opposed tariffs and other protectionism), that the ad never mentioned Trump or current U.S. policy, that Ontario is a province and thus acting independently of the Canadian government negotiating with the United States on trade, and that Trump himself has repeatedly criticized Reagan for supporting free trade. No, suddenly Reagan was actually a tariff-loving protectionist, and Ontario’s “lie” was sufficiently triggering for Trump to impose new, immediate, and unilateral U.S. taxes on hundreds of billions of dollars-worth of imports from one of the United States’ closest allies.

It’s just the type of “mad king” move that would’ve been considered too hysterical and absurd if I’d used it last year as a slippery-slope hypothetical on the risks arising from unbounded presidential tariff powers under IEEPA. And if the court decides that the president can do stuff like that under IEEPA (and without Congress), he can do almost anything—especially given the law’s broad wording about the types of transactions that could be regulated.

I don’t know how the Supreme Court will rule on Trump’s IEEPA tariffs, and I’ve called it a coin toss for more than a year. But the stakes really couldn’t be much higher—and certainly not just for the businesses and individuals from whom the U.S. government has taken billions of dollars.

Chart(s) of the Week