Alas, all you tech-optimists, the artificial intelligence revolution is seemingly everywhere except in the economic statistics. That’s the downbeat conclusion from JPMorgan strategists, who have scoured the macro data for green shoots of a big-time productivity revolution—and come up empty-handed. For now, the ChatGPT era is more show than substance.

“If large long-term productivity effects of AI are in fact realized,” they write, “we believe that they largely lie ahead of us.”

To gauge what may come, the authors sensibly look to what came before. The late-1990s IT boom remains the most instructive precedent. Between the mid-1990s and early 2000s, American labor productivity surged to three percent per year, nearly double the pace of the prior decade and a half. The biggest early winners were the tech companies themselves: Productivity in the computer and electronics sector soared to 21 percent annually in the five years ending 1999, while the data processing and internet sector clocked in at 13 percent by the mid-2000s.

Crucially, during the IT boom, productivity gains in tech-producing sectors led the broader economy by several years. But so far, the evidence is underwhelming that the clock is even ticking on such a timeline today.

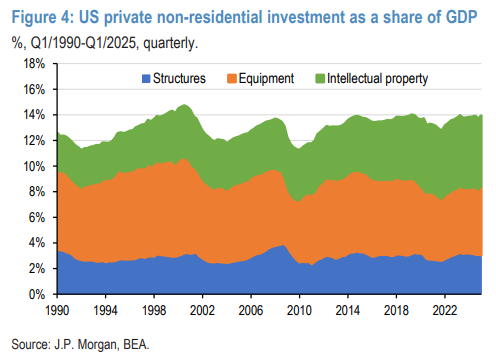

Productivity growth in AI-heavy industries like software and computer systems design has been “quite modest,” the analysts conclude. And while investment in data centers is ramping up, there has been no echo of the 1990s boom in private nonresidential investment, which climbed from 11.2 percent to 14.7 percent of GDP in less than a decade:

In our view, it is reasonable to expect a similar run-up in investment as AI tools are developed and deployed, though any such increase is not yet clear at the macroeconomic level based on [US private non-residential investment as a share of GDP].

The bank also offers a cautious note on what to expect if a productivity acceleration does actually emerge (bold by me):

It is, however, not a foregone conclusion that AI will in fact deliver large long-term productivity gains. Important changes in the ways in which people work do not always show up in the national economic accounts. There is, indeed, still much debate about its potential. More optimistic views are typically grounded in the predictions of technologists and theoretical economic research. However, nascent empirical economic research is far from emphatic, with some research finding that productivity gains are likely to be quite modest. At the low end of the spectrum, Acemoglu (2024) argues that total factor productivity (cf. labor productivity) gains could amount to 0.66% over 10 years. Haskel argues that a broader approach to the question indicates larger labor productivity gains of 0.7% per annum. Ultimately, it is still too early to predict the long-term impact of AI on productivity with any great confidence. That said, informed by the admittedly limited body of empirical research on this question, our bias is to be somewhat wary of claims that the labor productivity gains will far outstrip what was observed during the IT revolution in the US. Nevertheless, our base case expectation is for a meaningful pick-up in productivity growth that could be sustained for up to a decade, at least in some countries

While optimists patiently wait, they can take comfort from this bit of good news in the bank’s analysis: America appears best placed globally to reap the eventual rewards from an AI boom. It boasts so many of the right ingredients, especially high-skill immigration trained at elite universities and regulators who have so far opted for a relatively hands-off approach—another 1990s parallel. (“At the current juncture, the US still appears to benefit from these comparative advantages, though both are clearly policy-dependent and therefore far from guaranteed to persist.”)

For all the excitement—and the eye-popping valuations—AI’s golden age remains more tantalizing than tangible at this point. The latest technological revolution may well be here, but there’s a reasonable case that it is unlikely to be tabulated in the national accounts anytime soon.

The post Why the AI Dividend Isn’t Here Yet appeared first on American Enterprise Institute – AEI.