A little over a month ago, we first (and the Economist about a month later), summarized the plight of Japan’s soaring inflation and contracting economy with one word: rice…. well, technically it was a few more words. This is what we said:

What is ironic, is that Japan does not actually have high core inflation; it does however have soaring rice prices which have skewed inflation expectations across the population as rice is a huge component of the overall CPI basket. Meanwhile the BOJ is scrambling to contain inflation – which has tumbled ex food with real wages near record lows – and is tightening conditions by raising rates even though it has zero control over food inflation. However, as a by product of its monetary policies and strong yen, the bond market is crashing every day now, and soon this bond crash will spread to Japan’s banks and global markets, sparking a global crisis.

TL/DR: Japan will unleash the next financial crash because the Japanese are now poor farmers.

Fast forward to today when, with just two weeks until a critical election in Japan, attention is finally turning to this most important commodity for Japan… and perhaps the world. And it starts with Japan’s Nikkei profiling what we said was ground zero of Japan’s inflation crisis: rice farmers.

On a lush green plain bordered by mountains in northern Japan’s Yamagata prefecture, Nobuhiko Kurosawa does what 20 generations of his family have done before him: He grows rice. There is, however, a problem.

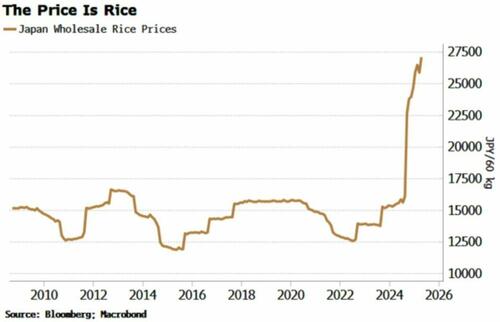

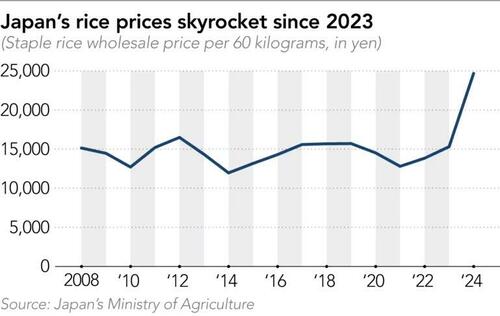

Tending to seedlings under a piercing June sun, Kurosawa finds himself in territory unfamiliar to his predecessors. A shortage of the commodity kickstarted by an extreme 2023 heat wave and compounded by an inability of the zombified, extremely heavily-subsidized local rice industry to quickly adapt to changing conditions, has sent rice prices skyrocketing, doubling within a year.

That shortage has brought rationing of sales in big-city supermarkets and made the humble staple of the Japanese diet the focus of a fierce cost-of-living debate in a campaign for an election to the upper house of parliament on July 20. Were the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) to lose its existing majority in the upper house, Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba’s position could be at risk, sparking a political crisis in Japan that could have profound consequences for both fiscal and monetary policy, not only in Japan but across the globe.

From his 30 hectares of paddies, Kurosawa supplies rice far and wide, from a nearby rice ball shop to businesses across Japan and overseas.

“We received inquiries from new customers, but we were unable to sell to them because we already had contracts with existing customers,” he told Nikkei Asia. “Our company also experienced a shortage of rice, and last year we had no choice but to narrow down our business partners before the summer.”

Meanwhile, Prime Minister Ishiba leads his conservative LDP toward the upper house elections with moribund approval ratings hovering in the mid-30% range, and inflation identified as the biggest issue of concern among survey respondents, according to a Nikkei/TV Tokyo poll. Just like in the US before Trump crushed Kamala Harris in every battleground state.

Having lost its majority in lower house elections under Ishiba’s stewardship last year, the LDP, the dominant force in Japanese politics for much of the last 70 years, needs to hold on to the slim majority it holds in the upper house, with a coalition partner, or face daunting challenges in pursuing a policy program as a minority administration in both houses. If the LDP performs poorly, Ishiba’s premiership will be in doubt, the Nikkei warns.

He faces a daunting uphill climb: the outrage around the soaring price of rice – hitting its highest this year for 30 years – has coursed through mainstream and social media debate in Japan for months. Recently even Donald Trump weighed in, criticizing Japan for not agreeing in increasingly tough trade talks to tackle the crisis by importing more U.S. rice, a move that would be viewed in a dim light by Japan’s farming lobby, a key LDP electoral base. It would, however, send the price of rice plunging, demonstrating once again just why government subsidies are always a two-edged sword.

“The rice shortage that began in the summer of 2024 was due to a shortage of rice produced in 2023,” according to Masayoshi Honma, distinguished professor at the Asian Growth Research Institute. “To compensate for this, advance purchases of 2024 crop rice have also occurred, driving up prices.”

Last year, demand for rice also surged due to the growing number of foreign visitors to Japan – a record 37 million – thanks to the plunging yen (which in turn sparked a burst of non-rice inflation higher) as well as a growing appetite for dining out and the relative affordability of rice compared to bread and noodles, said Kunio Nishikawa, a professor at Ibaraki University specializing in agricultural economics. Overall, Nishikawa calculates, “a supply-demand gap” of approximately 440,000 tons developed, an amount he estimates to be the equivalent of 1.8 months’ rice sales volume at supermarkets nationwide in Japan.

Since then, Japanese television news and talk shows have been filled with daily reports on people waiting in lines to buy rice, how to cook old rice so that it still tastes good and politicians’ statements about rice. In May a furor engulfed the then-agriculture minister after he said he had never bought rice himself as it was always presented to him as a gift by supporters.

Former prime ministerial aspirant Shinjiro Koizumi, a rising star in the LDP and son of a former premier, was swiftly appointed agriculture minister with a brief to get a grip on the rice crisis. Koizumi immediately pledged to halve rice prices to 2,000 yen ($14) per 5 kilograms, releasing government-stockpiled supplies in late May. Emergency stockpile sales, however, were promptly halted just hours later, after retailers snapped up all they could buy in apparent rationing amid soaring demand Still, shelves in the capital Tokyo are frequently empty as of early July as stores sell out, often rationing sales to one bag per family per day.

Which goes back to what we said almost two months ago: because the Japanese have become poor rice farmers, a global financial may be imminent. Some more background.

While many in Japan seek out rice for daily consumption, as the world’s fourth-biggest economy has developed (not to mention aged), so too have tastes for fancier and foreign foods. Demand for rice as a staple has dropped over recent decades to levels well below those seen in developing economies – to 73.5 kilograms per capita in 2022, according to World Population Review, equal to a third of Vietnam’s consumption.

As production of staple rice for Japanese consumers has fallen broadly in line with the demand decline in recent decades, production of rice for other uses – including animal feedstock and a small amount of exports – has begun to take off.

Shunsuke Orikasa, chief researcher at the Distribution Economics Institute of Japan, points out that as a result of a prolonged surplus of rice before 2023, “The price of rice had fallen to the point where producers would incur losses if they continued to grow rice as usual. For farmers, it was more profitable to switch to producing rice for non-staple use as instructed by the government and receive subsidies for it, so they moved toward reducing the amount of rice produced for the table.”

And then prices exploded.

Back in Yamagata, farmer Kurosawa said the delicate staple rice supply-demand balance has been upended. “Japan has been producing just enough to meet demand, so the extreme heat of the year before last was too much to handle,” he said.

On the other end of the supply chain, consumers are also concerned about the long term. A 26-year-old man living in Tokyo told Nikkei Asia he used to eat rice every day, but has changed habits due to the rise in rice prices since last summer.

“I’ve started eating pasta and udon noodles instead of rice, and I buy rice less often,” he said. While he welcomed lower prices since Agriculture Minister Koizumi was appointed, “I can’t say I approve of him because I don’t know what will happen to rice prices in the long term, and I don’t plan to go to vote.”

A 54-year-old woman living in Kanagawa Prefecture to the west of Tokyo said she also now shops differently. “The branded rice I used to buy online became too expensive, so I stopped buying it,” she said. “However, since rice is something I eat every day, I now buy rice sold at a nearby cheap supermarket.”

She welcomed Koizumi’s intervention, saying, “If he had not been in power, we would have had to buy rice at a higher price, so I’m grateful.” But she added, “I don’t want the LDP to become a one-party system, so I won’t vote for them.”

There is some good news: according to Japan’s Ministry of Agriculture, the average price of rice at supermarkets dropped 3.0% in the week to June 22, the latest date for which numbers are available, versus the previous week. But the news is mostly bad: at 3,801 yen per 5kg bag, the price was still up 71% year-on-year, although granted the price had been twice as high as the same period last year until recently.

Japan’s image as a global giant in rice is rooted in history: According to U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization data, it was the world’s fifth-biggest producer in 1970, but by 2020 it was in 11th position, one rank behind the U.S.

That decline began when Japan’s government implemented a policy of reducing staple rice production to maintain prices, starting around 1970, in part to retain the support of the farming lobby for the LDP, which has been in power for all but a few years since the mid-1950s. Although the policy was abolished in 2018, production adjustments continued through the system, such as subsidies for converting to other crops such as feed rice.

Yoshihisa Godo, professor at Meiji Gakuin University, said that what Japan is now dealing with is not a “rice shortage,” but a “shortage of staple rice.” The conversion of staple rice paddies to other crops has progressed, and the area of non-staple rice paddies has increased to more than 10% of total rice cultivation, according to Godo.

Amid the change in the rice business, the role of Japan Agriculture (JA), the national cooperative organization through which many farmers do business, is changing. Kazuhiro Koutsusa, a former JA employee and agricultural management consultant, said the percentage of rice sold through agricultural co-ops has declined significantly compared to several decades ago. Farmers can now communicate with buyers while working in the fields, finding customers themselves thanks to the spread of mobile phones, social media and the internet.

While the current staple rice price is roughly double that of last year, it remains at the same level as 30 years ago. In fact, Shigeru Someya, a rice farmer in Chiba Prefecture near Tokyo, said, “The rice prices of just a few years ago were less than half of what they were 30 years ago.”

Over the past few decades, the cost of machinery, materials, and fertilizers used in rice farming has risen, Someya said. At the time, the selling price of rice not only failed to increase but actually declined. Along with industrialization in adjacent areas offering new job prospects, that contributed to many abandoning rice farming. Someya currently cultivates rice on approximately 155 hectares of paddies, but the expansion of his operation was made possible by the fact that around 350 to 400 farming households that used to operate around his farm ceased rice production.

* * *

The government’s efforts to tackle rice price rises have been met with skepticism from the rice industry, with farmers and experts dismissing them as merely election-year measures that don’t address structural problems.

“Everything Koizumi is doing is election strategy; he is not talking about fundamental reform,” said Asian Growth Research Institute professor Honma, and he is right: what Koizumi is doing is literally identical to what Joe Biden did when he drained half of the US Strategic Petroleum Reserve to keep gas prices low in 2022 and 2023.

For the Distribution Economics Institute of Japan’s chief researcher Orikasa, the issue has wider implications. “From a broader perspective, the government’s attempt to control the price of a specific commodity in a free market economy is a challenge to capitalism,” he said.

Farmer Someya, meanwhile, expressed concern about Koizumi’s introduction of a standard price of 2,000 yen per 5kg bag. “While the government might say, ‘It’s 2,000 yen because it’s stockpiled rice,’ consumers might come to see 2,000 yen as the standard price even for new rice,” Someya said.

In the meantime, Japanese consumers are showing greater interest in imported rice than ever before, indicating a potential solution at least for buyers. Imports of staple food rice, subject to high tariffs, exceeded 10,000 metric tons for the first time in May, an increase of 126 times from the monthly average last year, according to data from the Ministry of Finance.

Aeon, Japan’s largest retailer, began selling blends of Japanese and American rice in April. In early June, it started selling California-grown Calrose rice, which it says is “selling better than expected.”

Reflecting at the end of a long day in his Yamagata paddies, farmer Kurosawa didn’t hide his concern for the future.

“The Japanese government has already released most of its rice reserves, so if this summer turns out to be as hot as the year before last, it could be disastrous,” he said. “If we have no reserves left and the quality of the rice has deteriorated due to the extreme heat, Japan may have to import a considerable amount. The food problem is not [just] a problem for farmers, but a problem for everyone who eats.”

At that time, Japan’s rice inflation – which also happens to be a component of the country’s core CPI – will explode and spark total chaos at the BOJ which will be scrambling to hike rates just because Japan’s farmers are unable to feed the country’s giant appetite for rice; in the process they will spark an economic depression.

Turning to the political dimension of the rice crisis, Bloomberg chimes in and writes that “a shortage of rice in Japan has caused the price of the household staple to surge, exacerbating the country’s cost of living challenges and fueling resentment among the population.”

As of June, a 5-kilogram bag of rice cost on average ¥4223 ($29.15) — almost double what it did a year ago. In some cases schools have cut back on the days they serve rice for lunch. Shops and restaurants have hiked the prices of their rice dishes.

With people angry over the record high prices, the issue has the potential to inflict damage on Ishiba and the ruling Liberal Democratic Party in elections this July.

The problem for Japan is that the outrage against Ishiba comes at a crucial time for Japan (the world’s most indebted nation by far): when it is facing a domestic fiscal crisis, coupled with trade war with the US.

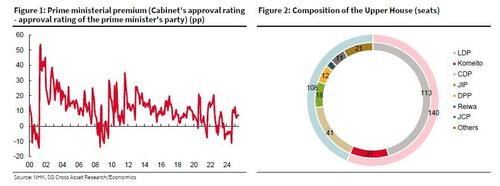

In a note published today by SocGen‘s Jin Kanzaki (available to pro subscribers), the strategist reminds us that the Upper House election is scheduled for 20 July, and writes that following the Tokyo Metropolitan Assembly election held on 22 June, the LDP is no longer the largest party there. However, both the cabinet’s and the ruling party’s (LDP and Komeito) approval ratings in early June rose by 6.0 and 4.7%, respectively, from May. This rise is thought to be due to a degree of appreciation for Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Minister Koizumi’s efforts to lower rice prices, namely dumping emergency stockpiled rice at low prices (in the process assuring much higher prices in the long-term). However, a survey conducted at the end of June showed that approval ratings for the cabinet and the ruling party had again fallen by 5.0 and 4.0%, respectively, from early June.

The election will test the performance of Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba’s minority government and the opposition parties. Key issues include inflation countermeasures—such as consumption tax cuts and cash handouts—and social security reform. A total of 522 candidates are expected to run for 125 contested seats, with the ruling coalition aiming to secure a majority when combined with its 75 non-contested seats. Opposition parties seek to prevent the ruling bloc from winning a majority of the contested seats. The outcome of tariff negotiations with the US, government efforts to lower rice prices, and the results in 32 single-member districts (where vote splitting among opposition candidates could benefit the ruling party) are expected to influence the election

As the ruling LDP has 75 seats that are not up for re-election this time, it can secure a majority with just 50 seats. Assuming that Komeito wins 10 seats and that the LDP wins a record low of 12 seats under the proportional representation system and one seat in each of the 13 multi-seat districts, the number of seats the LDP must win in single-seat districts to avoid losing its majority will be 15 seats. But given that the opposition parties are split among themselves while there are only 32 single-seat districts and the cabinet’s and ruling party’s approval ratings are declining again, at this stage SocGen only sees a 50-50 chance of the ruling party being able to maintain its majority.

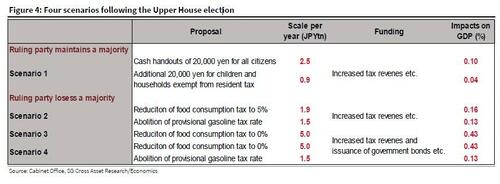

There’s much more in the full note (see here), but here is SocGen’s conclusion on the four most likely scenarios following the Upper House election:

Scenario 1 (50%): the ruling party maintains its majority

- The ruling party maintains its majority and Prime Minister Ishiba continues in office. In this case, cash payments will be implemented as part of the autumn economic measures, fiscal concerns will subside, and long-term interest rates will remain stable.

Scenario 2 (20%): the ruling party loses its majority and the next PM is Koizumi or Hayashi

- The ruling party loses its majority and Prime Minister Ishiba resigns. However, the ruling party will continue to form the government with a minority in both houses of the Diet as the opposition parties will refuse to join the coalition government. Either Minister of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Shinjiro Koizumi or Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshimasa Hayashi are likely to be selected as the next prime minister. In this case, as part of the autumn economic measures, the consumption tax rate on food will be lowered to 5% and the provisional tax rate on gasoline abolished. Meanwhile, long-term interest rates will rise initially, but eventually return to the level of Scenario 1.

Scenario 3 (20%): the ruling party loses its majority and the next PM is Takaichi

- The ruling party loses a majority, and Prime Minister Ishiba resigns. However, the ruling party will continue to form the government with a minority in both houses of the Diet while the opposition parties will not join the coalition government. Former Minister of Economic Security Takaichi will be selected as the next prime minister. Under this scenario, as part of the autumn economic measures, the consumption tax rate on food will be lowered to 0%, while long-term interest rates will rise from the beginning of the government’s term and remain high. In addition, the view that the BoJ will postpone rate hikes will become stronger, so the yield curve will steepen.

Scenario 4 (10%): a coalition government centred on the opposition parties is formed

- The ruling party loses its majority, and Prime Minister Ishiba resigns. As a result, a coalition government centred on the opposition parties (opposition parties + ruling party or opposition alliance) will be formed. Under this scenario, as part of the autumn economic measures, the consumption tax rate on food will be lowered to 0% and the provisional tax rate on gasoline abolished, so long-term interest rates will rise significantly from the beginning of the government’s term and remain high.

Bottom line: according to the French bank, there is a 50% chance that the outcome of the Japanese election in two weeks leads to a government crisis, which sends bonds yields in Japan soaring. And since global rates – especially at the long-end – are painfully interconnected in this day and age of soaring budget deficits, a bond market crash in Japan would also immediately result in a bond crisis around the globe.

Finally, what does all this mean for the yen? For one answer, we go to UBS Japan Execution Sales trader Sara Onozato who writes that “USDJPY is showing more signs of stagnation, with limited movement due to a lack of strong buying incentives for the yen and ongoing dollar selling driven by expectations of US interest rate cuts.”

As of June 30, the yen was trading around 144, with minimal monthly depreciation compared to more pronounced shifts in April and May. This stagnation is attributed to simultaneous weakness in both currencies. The dollar index has fallen to its lowest level since February 2022, while the yen has also weakened against European currencies, reaching 170 in EURJPY and 182 in CHFJPY.

In the futures market, net short positions in the dollar against major currencies have reached their largest levels in nearly two years. This trend is driven by expectations that the Federal Reserve Borad (FRB) is leaning toward a more dovish stance, favoring interest rate cuts. Market participants have fully priced in two rate cuts in the second half of the year and anticipate further declines in interest rates and a weaker dollar. Speculative net long positions in the yen are still high, limiting further upside.

The outcome of tariff negotiations between Japan and the United States is seen as a key factor, with the July 9 deadline approaching. The US administration has maintained a firm stance on imposing a 25% tariff on Japanese automobiles and criticized Japan for not importing US rice. The BoJ’s Tankan survey released on July 1 showed an unexpected improvement in business sentiment among large manufacturers. If tariff uncertainty clears, the BoJ could raise rates as early as September, potentially pushing the yen to 140 against the US. Conversely, stalled tariff negotiations could lead to further yen depreciation. The House of Councillors election on July 20 adds another layer of political uncertainty, especially after the ruling coalition lost seats in the Tokyo Metropolitan Assembly election.

UBS concludes that while most expect USDJPY to remain rangebound between 142 and 146, several key developments could push the pair beyond this range. A move toward 140 could occur if uncertainty around US-Japan auto tariffs is resolved and broader sentiment improves, especially following the BoJ’s recent Tankan survey, which showed an unexpected uptick in business confidence. This, on top of expectations for a BoJ rate hike, could create conditions that support yen strength. In contrast, USDJPY could climb toward 150 if tariff negotiations stall, triggering yen selling—particularly as many companies are expecting a smooth resolution. Political uncertainty from the upcoming House of Councillors election could further weigh on the yen.

Structural factors – such as Japan’s persistent trade deficit and the BoJ’s distance from rate hikes -may also limit yen appreciation, even amid broader dollar weakness. Overall, July could bring renewed volatility, with USDJPY direction hinging on how these economic and political events unfold.

Much more in the Socgen and UBS notes available to pro subs.

Loading…