Netflix has a Trump problem. The streaming behemoth, which two weeks ago seemed to have emerged victorious from a monthslong bidding war to acquire Warner Bros. Discovery’s (WBD’s) streaming and studio business, is now in the middle of one of the most dramatic corporate battles in Hollywood history. Not only was the company’s $72 million equity bid topped last week in a surprise hostile takeover effort by rival Paramount Skydance, the deal is now being intruded on by the president of the United States himself.

When asked about the deal at the Kennedy Center Honors ceremony on December 7, President Trump told reporters that Netflix already holding a significant share of the streaming market could pose an antitrust problem and that he would be part of any government decision to pursue action to stop or approve a deal. “They [Netflix] have a very big market share, and when they have Warner Brothers, you know, that share goes up a lot. So, I don’t know, that’s going to be for some economists to tell,” Trump said. “And I’ll be involved in that decision too.”

During an Oval Office meeting several days later, Trump spoke about the deal again, saying that CNN—a property owned by WBD and a frequent target of his attacks on the media—should also be sold as part of any agreement. “I think any deal, it should be guaranteed and certain that CNN is part of it or sold separately,” Trump said. “I don’t think the people that are running that company right now and running CNN, which is a very dishonest group of people, I don’t think that should be allowed to continue.”

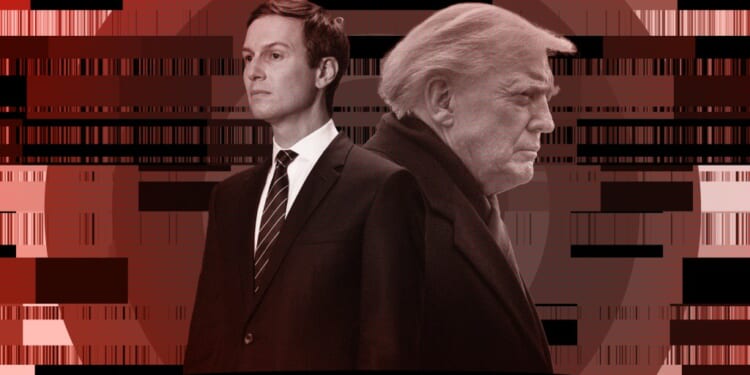

A president taking such a direct role in antitrust discussions—at least publicly—is unusual, and Trump’s close ties to Paramount Skydance’s bid—both political and familial—add yet another concern to a growing list of presidential conflicts of interest attached to the Trump White House.

WBD, which was formed in 2022 after AT&T spun off its WarnerMedia media business and merged it with Discovery, has been working to separate its more profitable studio and streaming businesses—which include properties like HBO Max, DC Entertainment, and Warner Bros. Studios—from its traditional television networks—like CNN and TNT—since last year. The media conglomerate has been formally in the market to sell those streaming and studio assets since the summer, the announcement of which sparked a bidding war among some of the country’s largest media businesses, including Netflix, Comcast, and Paramount Skydance.

On December 5, WBD and Netflix announced they had reached a deal for Netflix to acquire WBD at $27.75 per share following the separation of its traditional networks business late next year. The cash-and-stock deal assigned WBD a total enterprise value of around $83 billion, which would make it one of the largest corporate acquisitions of the decade. Only three days later, however, Paramount Skydance—which previously had seen several high-profile bids rejected by WBD—launched a hostile takeover bid of the entire WBD business, offering $30 per share in a direct appeal to shareholders. “WBD shareholders deserve an opportunity to consider our superior all-cash offer for their shares in the entire company,” Paramount CEO David Ellison said in a statement about the hostile bid. “Our public offer, which is on the same terms we provided to the Warner Bros. Discovery Board of Directors in private, provides superior value, and a more certain and quicker path to completion.”

Unlike Netflix’s agreement with WBD, Paramount’s bid is all cash, backed partly by the fortunes of the Ellison family and partly by three Middle Eastern sovereign wealth funds. Donald Trump has said that he considers both David Ellison and his father, multibillionaire Larry Ellison, as friends, and the president has long been allied with the elder Ellison politically. According to an SEC filing submitted by Paramount Skydance, financing for Paramount’s bid is also being supported by Affinity Partners, a private equity fund founded by Trump’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner, in 2022.

Last week, the Wall Street Journal reported that, during a recent meeting with the president, David Ellison promised Trump that Paramount would make “sweeping changes to CNN” should it succeed in acquiring WBD—something Trump’s remarks indicated he would favor. Ellison’s supposed promise to reform CNN has recent precedent. In October, Paramount, under Ellison’s leadership, acquired The Free Press for around $150 million and appointed its founder, Bari Weiss, as editor-in-chief of CBS News—a network division that drew similar ire from the president. Last October, Trump personally sued CBS News in response to a 60 Minutes interview with Democratic presidential candidate Kamala Harris that he claimed had been deceptively edited. Paramount settled the case with Trump for $16 million in July, shortly before federal regulators approved Paramount’s $8 billion acquisition by Ellison’s Skydance Media.

Trump’s close connections to Paramount’s bid for WBD via both Ellison and Kushner could pose a conflict of interest through Trump’s ultimate control over government antitrust authorities. These authorities, like the Department of Justice’s antitrust division and the Federal Trade Commission’s bureau of competition, are responsible for reviewing mergers and acquisitions and enforcing antitrust laws against deals that are deemed anti-competitive or otherwise against the interest of consumers. While antitrust law has often been prone to subjectivity, Trump’s direct involvement is atypical for presidents. “Trump wanting to be involved—wanting to have some leverage and some input—that’s really the biggest difference from past administrations,” Jessica Melugin, director of the Center for Technology & Innovation at the Competitive Enterprise Institute, told The Dispatch.

Antitrust enforcement has long been a contentious area of executive power, particularly because of its capacity to significantly delay, and sometimes prevent, corporate mergers and acquisitions. However, while antitrust was once largely based on the assumption that large companies were inherently prone to anticompetitive behavior, its enforcement has been relatively objective for decades. “From the 1980s until about 2016, antitrust enforcement was very consistent,” Jennifer Huddleston, a senior fellow in technology policy at the Cato Institute, told The Dispatch. “Even though you had both Democrat and Republican administrations during that period, [antitrust enforcement] was really focused on the consumer welfare standard, which was designed to be an objective, economically founded tool that looks at the purpose of antitrust as wanting consumers to benefit from a free and competitive market.”

That consumer welfare standard, however, which focused specifically on whether an acquisition would harm consumers, has recently ceded ground to a more aggressive approach known as neo-Brandeisianism that views all concentrations of economic power as suspect, even if they do not harm consumer welfare. This approach, which critics have labeled “hipster antitrust,” took root during the Biden administration and does not appear to have fully receded under Trump’s leadership. “It’s a return of this ‘big is bad’ mentality,” Huddleston said. “That really shifts the vision away from being focused on consumers, and instead puts a much more subjective and arbitrary measure that would allow the government to truly pick winners and losers and also risk interrupting naturally functioning markets.”

Antitrust experts like Huddleston and Melugin worry that a return to more subjective antitrust assessments may make it easier for presidents to leverage their authority over antitrust enforcement agencies to put a thumb on the scale of business deals like that between WBD and Netflix. “The consumer welfare movement was an effort to make things more objective by introducing economic analysis. … Let’s take the grift out, let’s pull the politics out, let’s get down to the numbers here,” Melugin said, describing the regulatory philosophy. But Trump’s direct involvement in the WBD deal, and particularly his suggestion that CNN must be sold and reformed as part of it, puts the politics right back in. “That is so outside the bounds of antitrust analysis that I’d dare to call it unprecedented,” Melugin said.

Whether Netflix emerges victorious or Paramount’s hostile takeover wins the day, the direct involvement of a president in antitrust considerations threatens to undermine public confidence in the objectivity of antitrust enforcement—something that antitrust authorities have worked for decades to avoid. “This is a tool that allows the government to really come in and dictate how a market is going to function,” Huddleston said. “We should recognize that antitrust is a very powerful tool, and we should be concerned about the politicization of it, regardless of which direction that’s coming from.”