You’re reading the G-File, Jonah Goldberg’s biweekly newsletter on politics and culture. To unlock the full version, become a Dispatch member today.

Dear Reader (especially you Bosnian Bruce Lee fans),

In the 16th and 17th centuries, Europe had a witch problem.

Actually, that’s not quite right. It had a witch hunt problem.

This was hardly a new issue. But it was getting out of hand, thanks in part to the printing press, which like all revolutionary media technologies, elicited a kind of populist upheaval. To listen to some people—a lot of people—witches were everywhere. Curses, hexes, and spells were making it difficult to get anything done. Mathilda turned my kid into a newt! Mary made my husband lustful for her! People, mostly women, were making pacts with demons and the Devil like he was giving out coupons for a free butter churn. The most common charges fell under the broad category of “maleficium”—“evil doing” or “wrong doing.” The annoying hag with the lazy eye at the edge of town made the crops fail—that sort of thing.

It got so bad, the Catholic Church felt it had to get involved. This made sense, after all. The church didn’t just have final authority on religion and morality where it held dominion, it also had the most educated scholars and legal minds in its employ.

The church’s Office of Inquisition was tasked with investigating these allegations. That’s really all “inquisition” means: an inquiry or investigation. Among the most famous of these investigators was the Spanish canon lawyer Alonso de Salazar Frías. In northern Spain one might say he was a one-man Catholic Supernatural Investigations (“CSI: Navarre,” coming soon to Netflix). He interviewed victims, he cross-examined women who’d confessed to being witches, and children who claimed to have attended nocturnal sabbaths. After eight months, he had compiled 5,600 folios of such affidavits.

In 1612, Salazar informed his superiors in Madrid of his findings. “I have not found a single proof, not even the slightest indication,” he wrote, “from which to infer that an act of witchcraft has actually taken place.”

The witch craze in Spain, as in much of Europe, had been a kind of moral panic fueled by outside preachers and stories of witchcraft in other regions. “I have observed that there were neither witches nor bewitched in a village until they were talked and written about,” Salazar said.

His final recommendation: This witchcraft thing is bunk and the church should have no tolerance for it.

He was not alone among Catholic witch-mythbusters. In Italy and other realms still under Catholic dominion, the church was instrumental in quelling the witch hysteria. Inquisitors would hold hearings at which evidence was demanded and testimony given under oath—and these were oaths that witnesses took pretty seriously. These hearings often revealed that charges of witchcraft were cynically or delusionally levelled. In newly Protestant parts of Europe, however, the witch craze continued, as secular nobles—often illiterate or semi-literate—succumbed to the populist frenzy. The “guilty” were often burned.

“During the 16th century, when the witch craze swept Europe,” affirms historian Thomas Madden, “it was those areas with the best-developed [Catholic] inquisitions that stopped the hysteria in its tracks. In Spain and Italy, trained inquisitors investigated charges of witches’ sabbaths and baby roasting and found them to be baseless. Elsewhere, particularly in Germany, secular or religious courts burned witches by the thousands.”

I do not bring this up to suggest that the church or its various inquisitions and inquisitors—there were many—were all saints or immune to criticism or condemnation (Though the Mel Brooks version of the Spanish Inquisition leaves much to be desired for historical accuracy). The contemporary fad for medievalism notwithstanding, it was a pretty terrible time all around. The Black Death, serfdom, stillbirths, rickets, and the promiscuous use of hot pokers and Iron Maidens by local authorities—not exactly selling points in my time-travelers’ vacation brochure.

But at least Salazar and the Catholic Church had the right idea: Look for the facts. Employ reason and skepticism to outlandish claims and accusations. Do not cave to the mob. Do not listen to people who reject appeals to facts and reason in service to passion and fear.

Witch craze days.

Let’s fast-forward to today. Charlie Kirk was murdered. The alleged murderer, Tyler James Robinson, was arrested after a member of his own family tipped off authorities. He hasn’t had his trial yet, but the evidence against him is compelling, including the claim that his DNA was found on the trigger and on a towel used to wrap the murder weapon. Robinson also allegedly told his roommate to delete incriminating messages. There’s more evidence, videotapes, prior statements, etc. But I’m perfectly happy to wait for the trial to say, at least as a legal matter, that he is the culprit and that his motives are fairly well established.

What there is no evidence of, whatsoever, is that Kirk was murdered at the behest of Israel, Israel supporters, Jews, etc.

But here is Megyn Kelly boasting, nay preening, to Tucker Carlson about her own courage in supporting Candace Owens’ “asking questions” about Israel’s involvement in the death of Charlie Kirk. Indeed, Kelly apparently has her own questions too.

I don’t want to dwell on Kelly, Carlson, or Owens because that’s what they want. But suffice it to say, that’s not how it’s supposed to work.

In our system, the accused get a fair trial, with legal representation. And the verdict of that trial reflects what is true to the best ability of our system to discover the truth. But our system is not perfect. We occasionally see wrongful convictions. At least as frequently, people who deserved conviction—or more severe punishment than they receive—get away with wrongdoing. We know there are far more crimes committed than arrests made, never mind convictions.

But my point isn’t about the criminal justice system. It’s about how we, as a society, “know” things. There was a time when people would argue about great controversies based upon what trials and investigations revealed. Now that process of discovery is often a sideshow or distraction for people who leap to conclusions heedless of facts.

It is almost impossible to “do your own research” on most issues. When people say they “do their own research,” they do not mean they go forth into the field like Salazar and interview witches or their victims. They mean they search the internet for the information they want to be true. But even in such cases, they are relying on other people who wrote the things they’re reading. If they’re searching government websites or reports, old news stories, books, etc., they aren’t doing the actual research that went into those things. They’re relying on the research of other people and institutions. Some of those sources are reliable. Some aren’t. Often, the “independent” researchers haven’t the foggiest clue which is which. And often they don’t understand what they are reading anyway.

For example, the people who glibly prattle about “the Jews”—or some other “they”—conspicuously avoid deferring to what investigators, courts, etc., find. In some cases, it’s simply a matter of refusing to wait for the facts. But in other cases, they assume that the courts, the cops, the lawyers—indeed, the whole monolithic concretized and reified “elites”—were all in on the cover-up. The fact that the “official story” is unsatisfying is often the proof of the conspiracy.

We see this almost daily with stories about the Jeffrey Epstein files. It was also the case for years with the Democratic National Committee, the Republican National Committee, and the pipe bombs planted near their headquarters on January 6, 2021. Say what you will about the Dreyfus Affair, but at least there was a (shameful) trial and a subsequent investigation. Today, people of influence or authority or both immediately leap to a script that has barely any relationship to the facts. How many people after the assassination attempt on Donald Trump in Butler, Pennsylvania, immediately insisted that “the left” or “they” tried to kill Trump?

There was no evidence for that then, and there is none now, because it wasn’t true.

This week, Donald Trump, J.D. Vance, and Kristi Noem broke with virtually every norm, tradition, and policy to simply assert what happened to Renee Nicole Good in Minneapolis virtually the moment the videos hit social media. Instead of saying we should all calm down and let the investigation take its course, they simply lied—Trump said the Immigration and Customs Enforcement agent who shot Good was “run over”—or exaggerated, or made stuff up. Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz and Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey didn’t react well, but they didn’t approach this level of irresponsibility (though I fear it is only a matter of time). New York City Mayor Zohran Mamdani did, by calling this homicide a “murder.”

The constitution of knowledge.

Courts aren’t the only institutions dedicated to finding facts and truth, nor are they even necessarily the most rigorous.

Science is a rich and complex system of institutions, in every sense of the word. Science is done in specific places: the National Institutes of Health, research universities, private sector labs, etc. But “institution” doesn’t just mean a physical place. In economics, an institution is a rule or set of rules. In science, too, there are rules, protocols, systems, procedures, etc. Hypotheses are formed. They get tested. The results are published. Other scientists scrutinize those results to find weaknesses and flaws. They see if the results can be replicated.

Journalism is another fact-finding, truth-seeking enterprise. And like science, it has rules and procedures. Journalism also benefits from competition among journalists. Brit Hume often likes to say if only one news outlet is “exclusively” reporting something for very long, it probably means it’s not true because other outlets can’t confirm it.

And of course, politics—at least politics in a liberal democratic society—is supposed to be about competitive fact finding and truth seeking. Congressional hearings are supposed to be adversarial. Partisans aren’t as bound to rules as court lawyers and scientists, but they too are expected to play a role in finding the truth, not least by trying to expose the falsehoods or exaggerations of partisans on the other side. Even elections are supposed to be arguments about what the government should be doing and why.

Trust in these institutions has been declining, for good reasons and bad, for a very long time. I can run through the reasons for another couple thousand words, but the story is familiar enough. Leaders of institutions on both left and right have abdicated their responsibilities. Whatever you think about the “trans” issue, the left’s bullying to get people to accept what millions considered a lie has done lasting damage to the credibility of those who did the bullying. Donald Trump’s insistence that the 2020 election was stolen—a flagrant and unapologetic lie that could not survive scrutiny in more than 60 courtrooms—has done even more damage.

People sneer at me when I uphold “norms.” Others roll their eyes when I talk about “both sides.” I get it. But a lot of that comes from partisans who want to claim that one side is dedicated to truth and the other to lies. This gets it wrong.

I don’t mind differences of opinion—I actually like differences of opinion and arguments. Vigorous disagreement about how to weigh the facts is what makes liberal society work. Jonathan Rauch wrote a brilliant book on the incredibly fragile ecosystem that makes the acquisition of knowledge possible, called The Constitution of Knowledge. I disagree with Jonathan on many things, but what I admire about him is his steadfast commitment to dealing in facts, in telling the truth. I’m a conservative, but I can have a conversation, even an enjoyable argument, with anybody who cares about such things. I have nothing but scorn and contempt for people who think the truth can simply be asserted or imposed through force of will. And I have a healthy fear of people who think passion alone creates truth. That is the path to witch burning.

Stories We Think You’ll Like

A Royal Paine

Without the pen of Thomas Paine, there may be no United States of America to celebrate today.

Various & Sundry

Canine Update

This feature was created because Zoë, our white trash swamp dog, was a sick puppy. I don’t mean that figuratively, though if you ever saw her take apart a groundhog, that label would fit. No, she was literally a very sick puppy. She almost died from parvo when we got her. People asked about her so much, I started including a “Canine Update” to inform people how she was doing. So today we’re returning to that original purpose. Yesterday, I drove Zoë to the surgeons to have her lump removed. She was such a good girl at the vet, even though she was clearly scared. The surgery, so far at least, seems to have been a success. They removed a 10-pound mass. She came home today. The doctors were worried because she wasn’t eating, but late today, after she got home, she noshed on some food. That is fantastic news. But this surgery wasn’t without risks. She has a lot of stitches, will be very prone to infection, and the mass could come back. But we have our fingers crossed. We miss her smile.The other animals are fine. Pippa had someconcerns, but she also seemed to enjoy being top dog, at least for a day. Gracie, as befits her nature, seemedunconcerned. It’s unclear if Chester knew anything about it.

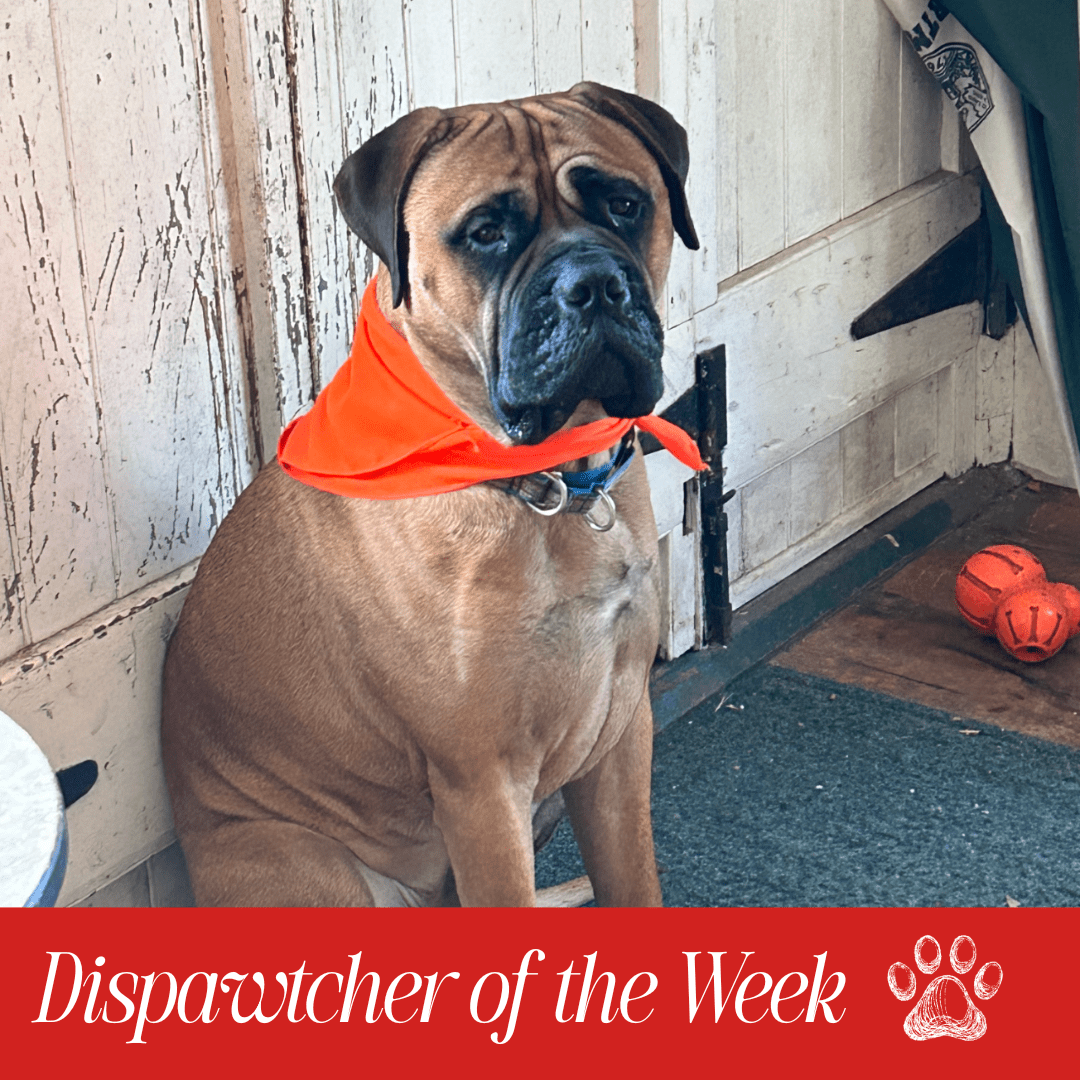

The Dispawtch

Member Name: Wendy Griswold

Why I’m a Dispatch Member: The Dispatch community is a natural home for someone who is center-right, interested in but not obsessed by politics, and dismayed by the way things are going in our country (but nevertheless has a life, and much to celebrate). I think I’ve been a member since the very beginning.

Personal Details: Professor, dog-and-cat lover, wife/mother/grandmother, passionate supporter of Ukraine—so I fit right in.

Pet’s Breed: Bull mastiff

Gotcha Story: Otis, from a breeder in Otisfield, Maine, is not a rescue. In our family we allow ourselves one purebred for every one rescue, and our other dog (recently deceased) was a Mastiff mix who had been returned to the humane society twice until she adopted us. Felix-the-cat is a rescue too, so we ARE somewhat virtuous.

Pet’s Likes: Eating. Lying on the couch. Eating. Curled up on the chair by the wood stove with his legs hanging off because he’s too big. Effusively greeting the UPS guy. Eating.

Pet’s Dislikes: Sometimes Felix takes over the chair. Otis stares at him for a few minutes, sighs, and lies down on the floor.

Pet’s Proudest Moment: A wonderful trainer has a course called “Tricks” in which dogs learn to do useless-but-amusing things that exercise their brains. Otis has mastered Circle, Go Around, and Peek-a-Boo. He’s a genius.

A Moment Someone (Wrongly) Accused Pet of Being Bad: It’s unfathomable to me, but when a bull mastiff lays his giant, slobbery head on someone’s thigh, it seems to bother some people. I say: Slobber happens; get over it.

Do you have a quadruped you’d like to nominate for Dispawtcher of the Week and catapult to stardom? Let us know about your pet by clicking here. Reminder: You must be a Dispatch member to participate.

Note: OK, one more week of no ICYMI and Weird Links, but they’ll be back!